Navenna

|

Republic of Navenna  Repùblega de Navenna (Navennese) |

Loading map... |

Navenna, officially the Republic of Navenna (Navennese: Repùblega de Navenna), also known as the Most Serene Republic of Navenna (Navennese: Serenìsima Repùblega Navennata), is a small sovereign state in southwestern Uletha bordering ![]() Plevia in the north and

Plevia in the north and ![]() Mardoumakhstan in the east. Located between the Mesembric Sea∈⊾ƨ in the west and the mountain chain in the east, the country covers a land area of 18,294.65 km² (7,063.60 sq mi) with a population of approximately 4.5 million inhabitants. The country shares its name with its capital, City of Navenna (Navennese: Zsità de Navenna), which is home to approximately a fifth of the country's population. Navenna is a constitutional elective monarchy, with a Doge (Navennese: Dòxe) as its head of state elected by the upper house, and a prime minister as its head of government elected by the lower house and appointed by the Doge. The Doge is a largely ceremonial role while the prime minister leads the government of Navenna. Navenna is a member of the Association of South Ulethan Nations and the Assembly of Nations.

Mardoumakhstan in the east. Located between the Mesembric Sea∈⊾ƨ in the west and the mountain chain in the east, the country covers a land area of 18,294.65 km² (7,063.60 sq mi) with a population of approximately 4.5 million inhabitants. The country shares its name with its capital, City of Navenna (Navennese: Zsità de Navenna), which is home to approximately a fifth of the country's population. Navenna is a constitutional elective monarchy, with a Doge (Navennese: Dòxe) as its head of state elected by the upper house, and a prime minister as its head of government elected by the lower house and appointed by the Doge. The Doge is a largely ceremonial role while the prime minister leads the government of Navenna. Navenna is a member of the Association of South Ulethan Nations and the Assembly of Nations.

There are few surviving historical records that detail the founding of Navenna. Historians believe that the Navennese Lagoon∈⊾ƨ may have been settled by peoples from Plevia or Pretannia. The city began as an independent city state, and grew to prominence after a power vaccuum emerged in the region in the 8th century. During the following years, the wealth of the fledgling republic grew due to its favorable position along important trade routes, and so did its influence, putting many cities on the mainland under its rule. In the 10th and 11th century, Navenna expanded south into Anoria, the name of the peninsula in the south of the country, integrating Anorian city states into Navenna with little resistance. During the 12th and 13th century, Navenna fought many battles against the Republic of Ƚovana and integrated much of the Shelakh states in the southeast. Territorial gains were also made in Nascillia∈⊾ƨ. The country grew rapidly during the 16th century expanding southwards along the Mesembric coast, establishing colonies and securing valuable trading posts. At its height, the Republic of Navenna reached as far south as modern day Lustria. Due to a multitude of factors Navenna's wealth declined during the 17th century, resulting in rapid loss of territories along the Mesembric coast. Since the 19th century, Navenna's borders have been relatively stable.

The country has an advanced economy based on finance, services and tourism. As an early industrializing country, Navenna used to have an economy based around mineral extraction and manufacturing. The decline of Navennese industry in the 1960s sent the country into a long economic depression. The depression was followed by sweeping economic liberalization that resulted in renewed economic growth primarily in the financial and service sector. Navenna ranks among the wealthiest countries in the world in terms of GDP per capita, although this has been partially attributed to distortions caused by disproportionate amounts of capital being moved through the country by various multinational entities operating in Navenna as a result of low corporate tax rates.[1] Various international economic institutions label Navenna as a major corporate tax haven.[2][3]

Etymology

The origin of the name "Navenna" is not entirely known. The earliest known mention of the name is from 722, using the form “Navienna”. The name is believed to have been constructed partly from the name of the original people inhabiting the Navennese lagoon, who based on historical records from the Romantian Empire were referred to as the Nāvies. This word in turn may have its origins from the Proto-Romantian word nāvis, meaning "boat". The ending "-enna" is a common oeconym in the Shelakh language which refers to a seat of power or center of rule. The name can therefore be deconstructed as having the meaning "seat of power of the Nāvies (Navennese)".

History

| History of Navenna | |

|---|---|

| Early republic | before 1122 |

| • First Navennese Republic | 655 |

| • Raiders of the East | 722-766 |

| • Navenno-Piavian War | 1055-1068 |

| • Treaty of Taragà | 1122 |

| Maritime empire | 1122-1778 |

| • War of the Councils | 1281-1288 |

| • The Embargo Wars | 1301-1304 |

| Modern nation | after 1680 |

Prehistory

The area that constitutes modern day Navenna is believed to have been inhabited for a very long time, likely since the Lower Paleolithic era. Artifacts dating back as far back as 800,000 years have been discovered in eastern Anoria. The petroglyphs of Falabiana are believed to have been made by modern humans some 35,000 years ago.

Early history

Origins

The origins of Navenna are uncertain, due to very few historical records and conflicting evidence. The ancient peoples who inhabited Navenna before the establishing of the Romantian Empire include the Nāvies, the Shelakh and the Aehorans. Discoveries of Shelakh artifacts dating back to 900 BC show that the Shelakh people were a dominant force during this early history and influenced much of the region, with the Nāvies and Aehorans being limited to the Navennese lagoon and western Anoria respectively. While the origins of the Shelakh peoples is unknown, the Nāvies and Aehorans are both considered Proto-Romantian cultures with origins from the north, possibly from Plevia or Pretannia. The Nāvies, being the likely namesake of Navenna, inhabited the Navennese Lagoon for thousands of years, long before the founding of the City of Navenna itself. They sustained themselves through fishing and salt production. The region's integration into the Romantian Empire brought with it cultural influences from the Romantian civilization, such as the Romantian writing system. After the collapse of the Romantian Empire, the following power vacuum lead to the establishment of several city states and kingdoms in the region. Years of Romantian rule is believed to have erased some of the cultural and ethnic distinctions between the Proto-Romantian peoples of the region.

The history of Navenna as a country is tied to its history as a city. Local folklore suggests that a major flood (referred to as El Gran Diƚuviòn, "The Great Flood") forced the population of the Navennese Lagoon to relocate, leading to the founding of a city on higher ground close to the barrier islands of the lagoon. The original ruling oligarchy of Navenna were made up of the families that emigrated from the lagoon into the city, while families from the mainland did not get the privilege of ruling the city. Historically such floods have occurred regularly, and other sources point towards such a flood occurring in the second half of the 6th century.

The First Republic

During its early years, the city state of Navenna is believed to have been ruled as an oligarchy by influential families. According to tradition, different families had sovereignty over different parts of the lagoon according to their land claims before the Gran Diƚuviòn. Because of this, the fledgling city state was dysfunctional and lacked order and vigor in its administration. The first Doge, Filadelfo Nùnxo, was elected by a council consisting of the ruling families in 655, to unite the fragmented city state under a single leader. Thus began a long tradition of influential and wealthy families electing the Doge to lead the country, effectively establishing an elective monarchy. This event is considered the beginning of the Republic of Navenna, and is commonly referred to as the First Navennese Republic (Navennese: Prima Repùblega Navennata).

It is not fully known when the name “Navenna” was first used to describe the city state. The earliest mention of the name “Navenna” comes from accounts of an invasion of the northeastern Mesembric region by raiders from the east, which occurred during the 8th century. Historical records of the sacking of Mirùn in 722 describe a city in the lagoon called “Nāviena”, which was a refuge for people fleeing from the raiders. The city was besieged in 724, a siege that ultimately failed due to the difficulties of fighting in marshes and tidal plains. A coalition of city states in the area, lead by Navenna was formed soon after the attempted siege in an attempt to repel the invading force. During this period, control of the land beyond the lagoon would be unstable and shift between coalition forces and raiders. When the invading force eventually collapsed and withdrew in 766, the city state of Navenna was able to exploit both its position as the de facto coalition leader and the power vacuum left behind by the raiders in order to assert control over the mainland - laying claim to cities in the modern day cantons of Navenna Lagunare, Malghexè and Alta Navenna. Mirùn and Malghexè would both grow to become important centers of power for the mainland. The city of Navenna rose to become an important trading center for the northeastern Mesembric region.

Middle Ages

Rise

The 10th century saw an expansion of Navennese influence into Anoria. Before its integration into the Republic of Navenna, Anoria was split between the Republic of Piavia, the Duchy of Seƚi and the Republic of Agheni. Through a combination of diplomacy and intimidation, the Duchy of Seƚi and the Republic of Agheni were both integrated into Navenna at the end of the 10th century, in 967 and 982 respectively. The Republic of Piavia resisted Navennese influence, and aligned itself with the Grand Duchy of Ƚovana, a rival merchant nation to the north of Navenna, for protection in 984. This had a domino effect on the nations of the region, who chose to align themselves with either Navenna of Ƚovana. While Navenna sought to claim cities and ports in the south along the Shelakhi coast, Ƚovana sought to secure itself against Navenna by seeking greater diplomatic ties with Plevian states in the north. In 1055, war broke out between the Republic of Piavia and the Republic of Navenna, which triggered a war between the two factions headed by Navenna and Ƚovana respectively. During the war, most of the remaining minor states of the region were either conquered or absorbed into Navenna and Ƚovana. The conflict was settled when the Navennese armada was destroyed outside the island of Fatamagia∈⊾ƨ in the Tiruglian archipelago in 1068 which caused Navenna to surrender. As terms for the surrender, the Republic of Navenna was to refrain from all trading activity in the sea north of Ƚovana. This caused Navenna to shift its trade ambitions from the sea to the land. While maritime trade would still be a significant source of income for the republic, Navenna also saw potential in establishing trade routes towards the east across the Ulethan continent. During the end of the 11th century, Navenna pushed northeast into the mountains, establishing trade routes with Plevian states, bypassing the Ƚovana-controlled waters. Trade relations were also established with Turquese and Surian states in the east, not only bringing wealth to Navenna but also cultural influences from Shelakhs, Turquese and Varvars.

The 12th century would see Navenna partake in various minor conflicts involving control over the Mesembric coast. Seeking to secure their ports along the Shelakh coast and create a hinterland to support the cities, Navenna would present the Shelakh states in the region with an ultimatum in 1122. The Shelakhs of the northeastern Mesembric coast were to swear loyalty to and become vassals of the Republic of Navenna, or their cities would be raized by the Navennese armada. All but one of the Shelakh states, the Kingdom of Mechna refused, which resulted in a drawn out conflict between Navenna and a coalition of Shelakh states. The Shelakh coalition navy was quickly decimated and the sacking of Thispoor (Navennese: Zsispora, Shelakh: Phispour) saw the end of Shelakh resistance along the coast. The Shelakhs would hold out much longer inland, but would ultimately be defeated at the Battle of Queshun. The Shelakh coalition would surrender after this defeat and were forced to sign the Treaty of Taragà. The treaty was much harsher than the original ultimatum, and would see much of the northeastern Mesembric coast integrated into the growing Navennese maritime empire and the Shelakh rulers completely deposed of. Some Shelakh rump states would remain to the east. At this time, Navenna streched from Aras in the north to Teraq-Tezan (Navennese: Taragà) in the south. The early years of Navennese rule in Shelakh lands were shaky, and it would take many years for a degree of tolerance between the peoples to emerge. Navenna sought to integrate Şelachia. The integration of the Coast of Shelakhs into Navenna resulted in a deeper cultural exchange between them, with Shelakhs and Navennans moving between cities and bringing their traditions and customs with them. While officially no institutional discrimination existed, in practice Shelakhs were often disadvantaged in Navennese society due to their differing language and religion. Navennan officials would often refuse to address Shelakh subjects in their own language. Law bringing protection for Shelakh language, religion and culture would be gradually implemented during the following centuries, though irrepairable damage to Shelakh cultural heritage had already been done.

| | |

|---|---|

| Birth: 1244, San Fiorenzxo, Navenna | Death: 1302, Tarasà, Navenna |

| Doge of Navenna; Father of the Second Republic | |

| Salvatore de Adaro was a member of the influential de Adaro family of Navenna and ruled as Doge of Navenna between 1284 and 1296. Salvatore de Adaro is most known for his role in the War of the Councils and the resulting reforms of the Navennese political system. During the election of a new Doge in 1281, the Council of One Thousand would elect Tulio Amorighi as Doge while most of the Council of One Hundred supported Salvatore de Adaro who was a member of said council at the time. Amorighi was well liked by the clergy, and wanted to extend the right of membership in the Council of One Thousand to more citizens, notably the clergy. De Adaro on the other hand sought to concentrate more power in the Council of One Hundred instead, making it more independent of other parts of the Navennese government, and was sceptical towards the Ortholic church. De Adaro was able to rally much of the petty bourgeoisie in his support, promising to extend the rights of Navennese citizens to partake in government if he was elected Doge. The situation escalated on November 8th 1281 when a mob stormed the halls of the Council of One Thousand, killing two council members. Amorighi and those loyal to him would barricade themselves inside the Castèƚo Serenìsimo. In an attempt to regain control of the city, Amorighi corresponded with loyalists outside the city, attempting to have the city besieged by the Navennese army in order to reestablish control. The siege lasted for almost 2 weeks but was ultimately unsuccessful, partly due to de Adaro being able to talk the navy into taking a neutral position in the conflict while still allowing supplies to reach the city by ship and therefore bypassing the siege. Amorighi was eventually exiled, while Salvatore de Adaro was crowned as Doge of Navenna in 1284. | |

A civil conflict, known as the War of the Councils (Navennese: Guèra dei Conséji) would break out in 1281 as a result of disagreements during the election of the next Doge of Navenna that same year. While the conflict was limited in scope and resulted in little actual violence, it influenced the de facto power dynamics between the social strata for centuries to come. The result of the War of the Councils was the crowning of Doge Salvatore de Adaro in 1284 which marked a shift in power among the ruling oligarchy from one with strong ties to the church to one with strong ties to the wealthy merchant class. Governance of Navenna after the War of the Councils would be marked by a more secular direction. As a result of this civil conflict, the Navennese governing system would see many reforms in the 13th century with much of the constitution rewritten by Doge Salvatore de Adaro, establishing the Second Navennese Reupblic (Navennese: Segónda Repùblega Navennata) in 1285. The power and independence of the Council of One Hundred would be strengthened, with the Council of One Thousand being reduced to primarily appointing members of other councils rather than taking policy decisions. Navennese democracy would reach its height in 1288 with the establishment of the Citizens' Assembly (Navennese: Senblèa dei Sitadìni). While progressive for its time, membership in the Citizens' Assembly was limited to residents of the city of Navenna itself, and the powers of the Assembly would be limited to deliberative powers and approving the Council of One Thousand's election of the Doge. This would mean that gaining the favor of the citizens would be crucial to getting elected as Doge, but the Assembly would have no say in how the Doge or any council ruled. This established a de facto class system in Navenna, consisting of the "aristocrats" (Navennese: ristocràti), members of the Council of One Thousand or Council of One Hundred who were often part of wealthy and influential families, the "citizens" (Navennese: sitadìni), residents of the city of Navenna who had the right to vote in the Citizens' Assembly, and the "provincials" (Navennese: provinsiaƚi), the population outside the capital city who could only partake in local governing.

Golden Era

After the fall of Ƚovana, Navenna had established itself as the sole merchant republic of the region, and effectively monopolized all trade along the eastern Mesembric coast. The wealth of Navenna rapidly grew during the 14th century, a time referred to as the golden era of Navenna. The golden era saw the establishment of the Shadow Council (Navennese: Conséjo Onbrìa), whose role was to maintain the power balance between the Council of One Hundred and the Doge.

Early Modern Era

Decline

Late Modern Era

Industrialization

The industrial revolution in Navenna started in the middle of the 1840s, having its epicenter in the northern regions. In the early stages of industrialization, Meletta was the premier city of industry in the country, thanks to the abundance of cheap coal and iron in the Ocetia Valley. As such, Meletta would grow from a minor fishing town into a significant port city, exporting Navennese steel. Since the pre-industrial economic centers of Navenna were located south of Ƚovana, there was a great demand to move resources from the resource-rich north to the major cities in the south. In order to stimulate industrial growth in the rest of the country, the first cross-country railway connecting all major cities from Meletta to Seƚi was constructed in the 1850s.

Great War

Post-war Era

Geography

| |

|---|---|

| Geography of Navenna | |

| Continent | Uletha (Western) |

| Region | Romantia |

| Population | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 41,585.67 km2 16,056.32 sq mi |

| • Water (%) | 55.3 % |

| Population density | 244 km2 633 sq mi |

| Time zone | WUT+4 (CUT) |

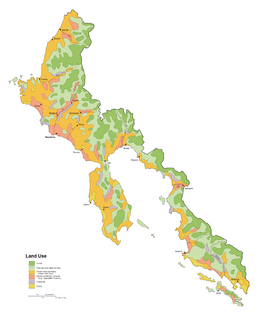

Navenna is one of the smaller states in Uletha; the country covers about 41,585.67 km² (16,056.32 sq mi), of which 18,578.92 km² (7,173.36 sq mi) is land. Navenna measures approximately 400 km in length and and 88 km in width at its longest and widest point respectively. The country is located along the northern shore of the Mesembric sea, and is considered part of the Ulethan region of Romantia. In Navennese, the region is normally referred to as the Upper Mesembric (Mesembrico Soràn).

To the north, Navenna borders the hilly and densely populated Plevian region of Nascilia. To the east, the country borders Mardoumakhstan. The border follows a mountain chain that stretches from southern Plevia to southern Mardoumakhstan. Along the border with Mardoumakhstan some of Navenna's highest mountains can be found.

Navenna can be roughly divided into three distinct geographical regions. The land closest to the west coast is relatively flat and low-lying, and are home to the bulk of the country's population centers and agricultural production. This is where the two large lagoons of Navenna can be found; the Navennese Lagoon∈⊾ƨ and the Zsianian Lagoon. The coast is sometimes more jagged, such as west of Ƚovana where the craggy islands of the Tiruglian Archipelago can be found. The northeastern part of Navenna is dominated by tall mountains and thick mixed forests. Most of the population here is found in the valleys between the mountains where orchards and pastures dominate the usable land. In the southeast the jagged mountains give way for a mosaic landscape with rolling hills where fields and pastures are interspersed with forests.

Shelakhia and Anoria in particular are home to a number of volcanoes. The Navennese volcanic arc runs roughly along the country's east coast, starting in San Uberto in the north and ending near the center of Shelakhia at Notrepo. Zsiforno, the country's largest volcano is continuously active with the latest large-scale eruption occurring in 2018. The area around Seƚi is known to be home to many dormant and extinct volcanoes, like Xeghèra. The volcanic soil in parts of Navenna is highly fertile and extensively cultivated wherever possible. Historians speculate whether this has been an important factor behind Navenna's high population density.[4]

A number of rivers can be found in Navenna. The river through Amsoana is nearly 800 km long and by far the longest river passing through the country, but most of the river is located outside Navenna. The longest rivers within Navenna are the Cesi and the Sane, at 92 km and 57 km respectively. Other major waterways are the Fior and the Atas. Navenna has a long history of waterworks, diverting rivers, building canals and reclaiming land. In the lowlands north of the City of Navenna exists a network of canals that historically provided a network for the transport of goods. Smaller streams were often redirected in order to serve as mill races for water wheels.

- Landscapes of Navenna

-

Pastures outside Rimì, Agheni

-

Orchards in the hills around Montrosari, Alta Navenna

-

The volcano Zsiforno viewed from Esèja, Anoria Sud.

-

Cliffs near Cièmeni, Breselo

-

Marshes near Polensetta, Fovènsia é Verana

-

Farmland near Ligo, Ƚovana Maxòr

-

View across the Cesi Valley from Sare, Malghexè

-

Mountains above Nòstra Siora, Montebiànco

-

View from Ocietia, Naşilia-Meletta

-

Waterways in the outskirts of Bragia, Navenna Lagunare

-

Asesa dei Xigànti as seen from Cadare, Paramo

-

Cliffs near Bòzo, Seƚi

-

Greenhouses around Piavia, Tesenso

-

Farmland around river delta near Sgia, Amsoana

-

View from above cliffs near Vos, Setóle

-

Old Shelakh fort near Latusa, Shelakhia

Climate

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Navenna has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa), characterized by hot and humid summers. Winters are mild and are marked by high precipitation. The country receives between 1,800 and 2,400 hours of sunshine on average every year, with an average of 8-11 hours per day in the summer, and 2-5 hours in the winter. Navenna's coastline often receives heavy rainfall in autumn and early winter due to its location west of a major mountain chain. The overall number of precipitation days is in relatively low, with precipitation coming in the form of heavy rain storms rather than light but consistent rainfall. There are on average 13.46 days annually with thunder, which is more common from May to October than other times of the year. In the country's interior the climate can vary greatly due to elevations above 1,000 meters above sea level.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Navenna was 45.9 °C (114.6 °F) on 12 August 2022.

Government and politics

| Government of Navenna | |

|---|---|

| Unitary parliamentary constitutional elective monarchy (de facto) | |

| Capital | City of Navenna |

| Head of state | |

| • Doge (Navennese: Dòxe) | Nestore Maestri |

| • Prime minister | Lidia Beƚoni |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| • Upper house | Council of One Hundred (Navennese: Conséjo del Sénto) |

| • Lower house | Citizens' Assembly (Navennese: Senblèa dei Sitadìni) |

| |

| Judiciary | Pretùra Èrta deƚa Repùblega |

Major political parties | |

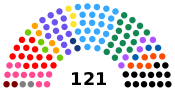

Government (52) Partido Repùblegano (22) Partido Christico Democratico (17) Aleanxa Progresiva (13) Confidence and supply (10) Unión Agraria (4) Partido Sociàle Christico (3) Ƚibartà é Jùstìsia (3) Opposition (59) Sociàldemocratisi – Partido dei Laorànti de Navenna (14) Nóva Democrasìa par Navenna (14) Senèstro Unìo (10) Forum parel Nord (6) Apalshelakh Motulum / Movimento Palaşelachi (5) I Vérdi (4) Confederasiòn Sindicàlista Nasionaƚe de Navenna (2) 3P - Partido Pari Pensionati (2) Partido Pirati (2) | |

| AN, ASUN | |

| | |

|---|---|

| Birth: February 12th 1953, Meletta, Navenna | Dòxe of Navenna since: November 2nd 2011 |

| His Serene Highness Dòxe of the Republic of Navenna (So serenìsima altexa Dòxe deƚa Repùblega Navennata) | |

| |

| | |

|---|---|

| Birth: February 12th 1969, Malghexè, Navenna | Prime minister since: October 19th 2019 |

| Her Excellency Prime Minister of the Government of the Republic of Navenna (So ecełensa Primo ministro del goèrno deƚa Repùblega Navennata) | |

| |

Government

The constitution of Navenna states that the country is a republic, ruled by a doge as the head of state, and a prime minister as the head of government. In practice, political scientists have described Navenna as a constitutional elective monarchy, with a representative parliamentary democracy headed by a constitutional monarch.

The position of doge is appointed by supermajority vote by the upper house of Navenna, the Council of One Hundred, and approved by the lower house, the Citizens' Assembly. Once elected, the doge rules for life unless dismissed from office by the Conséjo through a similar vote. Historically the doges have had far reaching powers similar to that of a monarch, but today the powers of the doge are limited by the constitution to a mostly ceremonial and representative role. The mandate of the doge includes the annual opening session of the Conséjo, and formally appoints or dismisses the grand councilor of the Conséjo. The doge hosts visiting foreign diplomats and represents Navenna during state visits abroad. Diplomatic letters such as letters of credence are often signed by the doge.

The Council of One Hundred (Conséjo del Sénto) is the upper house of the Navennese parliament. The powers of the Conséjo are primarily advisory, and often take the initiative to review and propose amendments to laws proposed by the government. The Conséjo cannot prevent normal laws from passing, but can veto any changes to the constitution of Navenna. Unlike the Senblèa, debates in the Conséjo can be conducted behind closed doors. The Conséjo has the power to both elect and dismiss the doge. The sessions of the Conséjo are presided over by a grand councilor (gran consejèr), who is appointed through a majority vote by the council and serves for a four year term. 48 of the 100 seats of the Conséjo are held by lords (sièri), who hold their seat for life or until they resign on their own, and are free to appoint their successor. The remaining 52 seats are appointed by non-partisan electors (eletori), who nominate members to the Council. In turn, the electors are appointed by the government whenever a new government term begins. Members of the Conséjo are not allowed to partake in partisan politics and in accordance with the constitution must act "in the best interest of the Republic". Members are automatically expelled upon conviction of any criminal offence that results in imprisonment.

The Citizens' Assembly (Senblèa dei Sitadìni) is the lower house of Navenna and the legislative branch of the state. The Senblèa passes all laws, approves the prime minister and their cabinet, and supervises the work of the government. Bills may be brought before the Senblèa by ministers or members of parliament. Members are democratically elected through a party-list proportional representation system. The method utilized for distributing seats combined with a low election threshold of 1% has resulted in a long history of many small parties. No single party has ever achieved a majority in the Senblèa, and all governments have either been formed by coalition or by minority one-party governments. The Senblèa is presided over by a speaker (parladór), who is elected by majority vote by members of the Senblèa. Formally, the Senblèa has the power to veto the election of the doge, though this power has never been exercised.

The government of Navenna, the executive branch of the state consisting of the prime minister and their cabinet, is approved by the Senblèa through negative parliamentarism. The main functions of the government are to present bills to the Senblèa, implement decisions taken by the Senblèa and appoint electors for the Conséjo. The position of prime minister is proposed by the speaker in consultation with the Conséjo. By precedent, the leader of the largest party in the Senblèa is always proposed to become prime minister, provided they can gather enough support from the other parties in the Senblèa.

Navenna has universal suffrage for all citizens above the age of 18. Elections for the Senblèa and the cantons are held every four years. Voters may choose to vote on a party only, in which case the party list is used to determine which candidates enter the Senblèa. Alternatively they may specify a candidate, or multiple candidates and rank them as they wish. Candidates do not have to be a member of a party to stand for an election, but independent members of parliament are very rare. In order for a political party to be allowed to be registered and stand for an election, they must collect certificates of support from a minimum of 16,000 voters.

Political parties

Any one party has a very slim chance of gaining power alone, and no party has ever won a majority of seats in any election. Therefore, it is political praxis that parties work with each other and form coalition governments. Traditionally, power in Navenna has been held by either center-right coalitions lead by liberal conservative Christic Democratic Party (Partido Christico Democratico), or center-left coalitions lead by Social Democrats - Workers' Party of Navenna (Sociàldemocratisi – Partido dei Laorànti de Navenna). The liberal Republican Party (Partido Repùblegano) is a third major political party that has supported both center-right and center-left governments. Other major political parties include liberal Progressive Alliance (Aleanxa Progresiva), national conservative New Democracy for Navenna (Nóva Democrasìa par Navenna) and socialist United Left (Senèstro Unìo).

| Party | Position | Ideology | Leader | Seats | International affiliation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | Republican Party Partido Repùblegano |

Center-right | Conservative liberalism Economic liberalism Pro-Ulethanism |

Lidia Beƚoni | 22 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

International Liberal Democratic Alliance (ILDA) | ||

| PCD | Christic Democratic Party Partido Christico Democratico |

Center-right to right-wing |

Liberal conservatism Christic democracy |

Ippolito Pecora | 17 / 121 rrrrriirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Alliance for Liberty (AL) | ||

| SD-PLN | Social Democrats - Workers' Party of Navenna Sociàldemocratisi – Partido dei Laorànti de Navenna |

Center-left | Social democracy Pro-Ulethanism |

Tonio de Adario | 14 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

International Alliance of Social Democrats (IASD) | ||

| NDpN | New Democracy for Navenna Nóva Democrasìa par Navenna |

Far-right | National conservatism Economic nationalism Hard Ulethascepticism |

Benedetto Arnoni | 14 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Alliance for Identity and Sovereignty (AIS) | ||

| APR | Progressive Alliance Aleanxa Progresiva |

Center to center-right |

Social liberalism Progressivism Pro-Ulethanism |

Serena Parmato | 13 / 121 rrrriirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Progressive International (PI) | ||

| SU | United Left Senèstro Unìo |

Left-wing to far-left |

Democratic socialism Feminism Green politics |

Emilia Montanari | 10 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

International Alliance of Social Democrats (IASD) | ||

| F | Forum Forum |

Syncretic | Regionalism Populism Soft Ulethascepticism |

Celino Varano | 6 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Unaffiliated | ||

| AM | Apalshelakh Movement Apalshelakh Motulum / Movimento Palaşelachi |

Syncretic | Federalism Minority rights Pro-Ulethanism |

Sofia Thunarch | 5 / 121 riirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Unaffiliated | ||

| UA | Agrarian Union Unión Agraria |

Center | Agrarianism Liberalism Green politics |

Avitus Terzi | 4 / 121 riirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Progressive International (PI) | ||

| V | The Greens I Vérdi |

Center-left | Green politics Progressivism |

Glaucia Ongariano | 4 / 121 riirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Progressive International (PI) | ||

| LJ | Liberty and Justice Ƚibartà é Jùstìsia |

Right-wing | Social conservatism National conservatism |

Vittorino Silvestri | 3 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Alliance for Liberty (AL) | ||

| PSC | Christic Social Party Partido Sociàle Christico |

Right-wing | Christic democracy Social conservatism Political Ortholicism |

Àngela Como | 3 / 121 rrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Alliance for Liberty (AL) | ||

| CSNN | National Syndicalist Confederation of Navenna Confederasiòn Sindicàlista Nasionaƚe de Navenna |

Far-left | Socialism Syndicalism Hard Ulethascepticism |

Onofrio Tosetti | 2 / 121 iirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

International Workers' Alliance (IWA) | ||

| 3P | 3P - Party for the Pensioners 3P - Partido Pari Pensionati |

Syncretic | Pensioners' interests Soft Ulethascepticism |

Gervasio Quaranta | 2 / 121 iirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

Unaffiliated | ||

| PP | Pirate Party Partido Pirati |

Syncretic | Pirate politics Civil libertarianism Direct democracy |

Sofi Hakobyan | 2 / 121 iirrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr |

World Libertarian League (WLL) | ||

Constituent Entities

| |

|---|---|

| Administrative divisions of Navenna | |

| First-level | 19 cantons (Navennese: cantoni) |

| Second-level | 197 municipalities (Navennese: comùni) |

| Third-level | 2 metropolitan cities (Navennese: zsite metropolitane) |

Navenna is divided into 19 cantons, which are further divided into a number of municipalities (Navennese: comùni). The cantons of Navenna enjoy a degree of self rule and have their own tax base as mandated by the constitution. The extent of their responsibilities are further regulated by national law, thus the cantons are interdependent upon the national government. The Navennese constitution specifies some requirements regarding how local administration of a canton is conducted, but does allow a great deal of freedom regarding how the cantons' administrations are internally structured. For example, Navenna Lagunare has the largest population out of all cantons and thus has many more institutions than other cantons. Navenna Lagunare has within a part of its territory chosen to delegate some competences to the Metropolitan City of Navenna∈⊾ƨ, an association of municipalities within the urban area of the City of Navenna.

Another example of the assymetrical structures of cantons is language. In the cantons of Şelachia∈⊾ƨ and Ghiana∈⊾ƨ, Shelakh is an official language and thus the cantons conduct their official work in both Navennese and Shelakh. In Paramo canton∈⊾ƨ, Arasian has been designated a "protected language" by the canton. While daily affairs are usually conducted solely in Navennese, Arasian speakers have been given the right to request any comunications between them and the canton to be conducted in Arasian. The municipalities of Aras∈⊾ƨ and Cadere∈⊾ƨ do not have the power to designate Arasian an official language on their own, but as a consequence of the canton's directive, in practice conduct most work in both Navennese and Arasian.

| Flag | Canton | Capital | Number of municipalities |

Land area | Population | Population density | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km² | mi² | km² | mi² | |||||

| Agheni∈⊾ƨ | Agheni | 10 | 855 | 330 | 171,000 | 201 | 518 | |

| Alta Navenna∈⊾ƨ | Mirùn | 16 | 1,008 | 389 | 158,700 | 157 | 408 | |

| Anoria Inferiór∈⊾ƨ | Cáglia | 13 | 1,408 | 544 | 102,045 | 72 | 188 | |

| Breselo∈⊾ƨ | Breselo | 10 | 1,016 | 392 | 152,190 | 150 | 388 | |

| Ghiana Giang∈⊾ƨ |

Nosporà Nouspour |

1 | 102,000 | |||||

| Ƚovana Maxòr∈⊾ƨ | Ƚovana | 23 | 1,721 | 664 | 624,521 | 363 | 941 | |

| Malghexè∈⊾ƨ | Malghexè | 7 | 356 | 137 | 110,256 | 310 | 805 | |

| Marca Piaviana∈⊾ƨ | Tesenso | 6 | 419 | 162 | 82,076 | 196 | 507 | |

| Montebiànco∈⊾ƨ | Guinevento | 5 | 510 | 197 | 56,209 | 110 | 285 | |

| Naşilia-Meletta∈⊾ƨ | Meletta | 8 | 1,058 | 409 | 241,004 | 227 | 589 | |

| Navenna Lagunare∈⊾ƨ | City of Navenna | 22 | 694 | 268 | 1,030,856 | 694 | 3,846 | |

| Paramo∈⊾ƨ | Paramo | 11 | 1,011 | 390 | 120,899 | 120 | 310 | |

| Rosarà∈⊾ƨ | Rosarà | 11 | 1,456 | 562 | 310,507 | 213 | 553 | |

| Saranna∈⊾ƨ | Amsoana | 6 | 1,040 | 401 | 213,049 | 205 | 531 | |

| Seƚi∈⊾ƨ | Seƚi | 11 | 722 | 279 | 213,900 | 296 | 767 | |

| Setóle∈⊾ƨ | Osilia | 5 | 359 | 139 | 132,651 | 370 | 954 | |

| Şelachia Shelaqalum∈⊾ƨ |

Malmaca Malmlac |

20 | 3,639 | 1,405 | 418,089 | 115 | 298 | |

| Zsiana∈⊾ƨ | Zsiana | 8 | 722 | 279 | 152,400 | 211 | 546 | |

| Zsispora∈⊾ƨ | Thispoor | 4 | 134 | 51 | 252,680 | 1,886 | 4,955 | |

Foreign relations

Military

Economy

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy of Navenna | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Social market economy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Navennese Ducat (∂) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • Per capita | |||||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2020) | very high | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Principal exports | cars, machinery and equipment, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, financial services, unclassified transactions | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Principal imports | raw materials, metals, machinery and equipment, chemicals, foodstuffs, transportation equipment, petroleum products, textiles, clothing | ||||||||||||||||||||

Industries and sectors | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Main export partners Main import partners | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wealth inequality index | medium | ||||||||||||||||||||

Navenna has a globalized, high income mixed economy which features moderate growth and high GDP per capita. Navenna's main imports are raw materials, metals, machinery and equipment, chemicals, foodstuffs, transportation equipment, petroleum products, textiles and clothing. Financial services and unclassified transactions constitute a significant part of Navenna's exports. Other major exports include natural gas, cars, machinery and equipment, chemicals, pharmaceuticals. Navennese agriculture meets 62% of the domestic food demand, but also exports dairy products, wine and olive oil. Tourism is a significant source of employment, especially in the southern parts of the country where some cities are reliant on tourism for the local economy. The historical city center of Navenna is a world renowned tourist attraction visited by around 5.2 million tourists in 2021.

Historically, Navenna has been a highly industrialized country with an economy based around mineral extraction and manufacturing. Mining and steel production flourished during the early 19th century, especially in the cities of Tessa and Meletta which were both located in regions rich in iron ore and bituminous coal. Anoria has been economically reliant on natural gas from the Caƚia∈⊾ƨ gas field since the 50s. The City of Navenna, Thispoor and Seƚi have long been major port cities and centers for the Ulethan shipbuilding industry. The economies of Malghexè and Mirùn were historically linked to the textile industry. As manufacturing costs became higher, and the industry had to increasingly rely on imports of natural resources, Navennese industry became less competitive with many companies either moving their production abroad in search of cheaper labor, or went bankrupt. Ever since the recession of the 1960s, the manufacturing sector has been of lesser importance in Navenna, but a few significant companies remain. Renavali, a merger of Navenna's ship manufacturers operate a number of shipyards outside Navenna, such as in Goukamma, CCA∈⊾ƨ. NASEC∈⊾ƨ, Navenna's largest defense contractor has been able to stay competetive due in part to the company branching out into infosec, and due to NASEC's close ties to the Navennese state which has ensured continued funding. Rosolini is a major foodstuff conglomerate which owns multiple brands produced and sold all over the world, and operate subsidiaries in Qennes and Freedemia, among others. Some industries have survived by catering to niche markets, such as vehicle manufacturer Regòra∈⊾ƨ which exclusively produces sports and luxury cars.[5]

Navenna's current economy is primarily based around finance and services, and has been able to rapidly develop its economy through its favorable corporate tax policies. The country is also known for its strict banking secrecy, with major Navennese banks such as BMN and SBNS being accused of being safe havens for tax evasion, money laundering and other types of financial crime. Foreign multinational companies constitute a significant part of the country's total economic activity, employing around 20% of the country's private sector workforce and paying nearly 70% of the collected corporate tax. Tax practices of primarily foreign but also domestic multinational corporate entities has caused Navenna to have a greatly distorted GDP, since it includes income from non-Navennese companies[1]. These distortions are believed to have positive effects on both domestic consumer optimism and global investors, and additionally masks underlying economic economic issues. Navenna suffers from high wealth inequality compared to many other countries in the region, and has a higher poverty rate than the ASUN average. While Navenna usually performs well in terms of economic freedom and ease of business, several studies note an increasing prevalence of oligopolistic structures in various sectors, notably in retail, housing and telecommunications.

Infrastructure

| Infrastructure of Navenna | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roadways | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Driving side | Right | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Minimum age | 18 (motor vehicles) 15 (mopeds < 125cc) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Maximum speed | Motorway: 130 km/h Expressway: 100 km/h Rural: 80 km/h Urban: 40 km/h | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Railways | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Passing side | Right | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Gauge | 1435mm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Electrification | Varies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrical power generation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mains electricity | 230 V, 50 Hz | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .na | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also: Infrastructure in Navenna

See also: Infrastructure in Navenna

Navenna has a developed network of road and rail. Most major cities are served by the Navennese autostrade, a network of tolled motorways owned by the state but operated by the private company Autostrade per Navenna. The longest of these is the A-1 connecting the City of Navenna with Ƚovana and Plevia. Some cities are served by non-tolled expressways called superstrade. In 2019, there were about 683 cars per 1 000 inhabitants in Navenna.[6] While efforts have been undertaken to reduce car use and promote the use of public transport, car dependency has steadily increased since the 1980s.

The national railway network is state owned and operated by SFR. Most of the network is electrified. Most railway lines along the coast and between major cities are double-track, while railways going east into the mountains are mostly single-track. Navenna's sole high-speed railway connects the City of Navenna with the Plevian capital of Osianopoli via Ƚovana and Condona.

More than 90% of all airways traffic in Navenna is handled by a single airport, Aereoporto internasionaƚe de Navenna Xeƚo∈⊾ƨ. The airport serves as the hub for Navenna's only airline and flag carrier ARN - Navennese Airways.

Power production in Navenna is highly reliant on the Caƚia gas field. After the gas field's discovery in 1953, a network of pipelines was constructed connecting the Caƚia gas field with population centers both within and outside Navenna. Gas levels are believed to reach low enough levels that extraction is no longer economically feasible around 2030-2035. Therefore the country has been diversifying its power production in recent years. Hydroelectric power has been a complementary source of energy in the country's interior regions for many years, and plans for expansion into previously unregulated rivers has been put forward. Pilot projects using biomass and biogas as a replacement for the previously gas-reliant thermoelectric plants are currently underway.

Demographics

| Demographics of Navenna | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demonym | Navennan, Navennese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Navennese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized minority languages | Arasian, Shelakh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnicities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Life expectancy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With an estimated population of 4.5 million, Navenna ranks among the smaller countries of the world in terms of population. Most of the population lives in the coastal central parts of the country; almost one forth of the population can be found in the City of Navenna's metropolitan area, and the cantons of Navenna Lagunare∈⊾ƨ and Ƚovana Maxòr∈⊾ƨ are home to approximately half of the population. With a population density of 248 inhabitants per square kilometer, Navenna is among the more densely populated countries in the world.

Ethnicity

The constitution of Navenna states that a Navennan is anyone who is a citizen of Navenna. Navennese people share a common origin with Plevo-Valonian peoples, but with a significant admixture of West Turquan groups. Historically, the nation of Navenna has controlled coastal areas throughout the Mesembric sea and thus have intermixed to a degree with various Mesembric peoples, such as Mardoumakhs, Yughuts, Mharetics and Larcetans.

Shelakhs make up the largest ethnic minority in Navenna, with around 9 percent of the population self-identifying as such. Due to historical Shelakh lands having been integrated into Navenna for centuries, differences between Navennese and Shelakh peoples have been diminished, with many persons with Shelakh ancestry self-identifying as Navennese or as Navennese and Shelakh in equal part. Most ethnic Shelakhs live in Shelakhia∈⊾ƨ, together with most ethnic Mardoumakhs who make up the second largest ethnic minority in Navenna. The third largest ethnic minority, Arasians, are a Plevo-Romantian people who primarily inhabit the Paramo canton∈⊾ƨ.

Navenna is a significant destination for immigrants, with the country's population growth being mostly thanks to immigration. It is estimated that about 11% of the country's population are foreign-born immigrants or Navennese-born descendants of immigrants. Most immigrants hail from other ASUN nations, mostly from Mardoumakhstan, Plevia and Demirhan Empire.

Language

Religion

Education

Health

The overall life expectancy at birth in Navenna varies greatly between sexes; 78.6 years for males versus 85.1 for females. This disparity has decreased over the last 25 years as male life expectancy has increased faster than female life expectancy. The total fertility rate of Navenna was 1.77 in 2018, and has decreased considerably since after the Great War. While the natural growth rate of the population is currently negative, population has been increasing throughout the 21th century thanks to a high immigration rate, primarily from other Mesembric countries. Like many developed nations, Navenna has a high average age compared to the world average, at 44.1 years.

Navenna's healthcare system is based on mandatory health insurance. All citizens must take out their own healthcare insurance from any private for-profit or NGO insurance provider. Healthcare insurance is regulated by law; all insurance providers must offer a universal and affordable insurance package, and may not refuse or impose special conditions upon the applicant, except under very specific circumstances.[7] Risk variations are managed through a national risk equalization pool managed by the state, and insurance providers are incentivized to take on high risk individuals through compensation. Children below the age of 18 are automatically covered by their parents' healthcare insurance plan. Individuals below a certain income threshold receive subsidies from the state to help pay for healthcare insurance. Health expenditure per capita amounted to 5,344 USD per year in 2018.

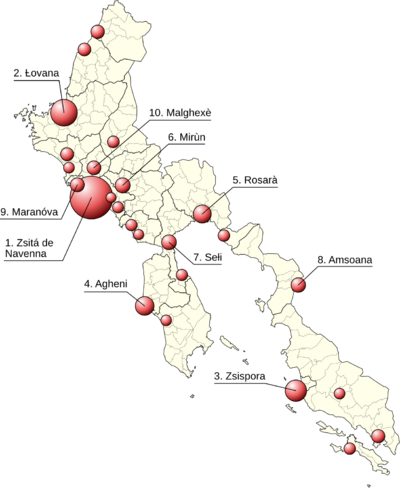

Major cities

Navenna is a highly urbanised country, with an urbanization rate of 82 percent. The largest city and capital is the City of Navenna with a population of 789,202 in its urban area. As a highly monocentric country, most economic, cultural and political activity takes place in the City of Navenna, with the exception of industrial activities which are instead more significant in the country's second and fourth largest cities - Ƚovana and Agheni respectively. Ƚovana has the country's largest port, serving as a major import and export gateway for Navenna and its surrounding region. Agheni has been historically significant as the capital of the ancient Anorian nations, and holds importance today for its gas industry. Zsispora is the country's third largest city and is the historical center of Shelakh culture.

| Symbol | City (canton capitals in italics) | Canton | Population (urban area) |

|---|---|---|---|

| City of Navenna | Navenna Lagunare∈⊾ƨ | 789,202 | |

| Ƚovana | Ƚovana Maxòr∈⊾ƨ | 315,612 | |

| Zsispora | Zsispora∈⊾ƨ | 198,202 | |

| Agheni | Agheni∈⊾ƨ | 155,040 | |

| Rosarà | Rosarà∈⊾ƨ | 145,087 | |

| Mirùn | Alta Navenna∈⊾ƨ | 102,201 | |

| Seƚi | Seƚi∈⊾ƨ | 98,520 | |

| Amsoana | Saranna∈⊾ƨ | 93,109 | |

| Maranóva | Navenna Lagunare∈⊾ƨ | 88,406 | |

| Malghexè | Malghexè∈⊾ƨ | 85,075 | |

| Meletta | Naşilia-Meletta∈⊾ƨ | 81,711 | |

| Malmaca - Malmlac | Şelachia - Shelaqalum∈⊾ƨ | 79,342 | |

| Zsiana | Zsiana∈⊾ƨ | 78,520 | |

| Breselo | Breselo∈⊾ƨ | 66,908 | |

| Paramo | Paramo∈⊾ƨ | 61,780 | |

| Nosporà - Nouspour | Giang - Ghiana∈⊾ƨ | 60,084 | |

| Osilia | Setóle∈⊾ƨ | 59,133 | |

| Tesenso | Marca Piaviana∈⊾ƨ | 58,670 | |

| Migia | Seƚi∈⊾ƨ | 55,809 | |

| Luli | Navenna Lagunare∈⊾ƨ | 52,231 | |

| Tessa - Tezintha | Şelachia - Shelaqalum∈⊾ƨ | 51,289 | |

| Fovènsia | Zsiana∈⊾ƨ | 46,550 | |

| Cáglia | Anoria Inferiór∈⊾ƨ | 45,201 | |

| Piavia | Marca Piaviana∈⊾ƨ | 42,489 | |

| Bragia | Navenna Lagunare∈⊾ƨ | 41,387 |

Culture

Music

Internationally, Navenna is not regarded as a major music nation, and is often overshadowed by other Mesembric states. Domestically, Navenna has a rich and varied music scene, and is home of a number of unique music genres that have spread around the world. Notably, contemporary Navennese music has heavy international and electronic influences.

While traditional Navennese folk music has fallen in popularity since the late 1900s, folk music is still an important part of Navenna's cultural heritage. Due to the country's location at the meeting point between Romantian and Turquese Uletha, Navennese folk music shares elements from both Plevian and Turquese music traditions. Northern Navenna shares many elements of traditional Nascilian music, while the south and east has influences from Shalekh, Varvar and Turquese music. Navennese folk music is usually homophonic and characterized by simple melodies and harmonies. Themes portrayed can vary greatly; folk music can have simple and abstract themes such as love, death, friendship or food; or more specific themes such as historical and mythological events or holidays.

During the high renaissance, the City of Navenna was an important center of the arts in Romantian Uletha. In contrast to the simplicity of folk music, Navennese classical music is well known for its "masimalista style" with grand orchestras and complex polyphonic harmonies pioneered by composers such as Ciro Nenci and Sabino Razsi in the late 1500s. One of the most well known Navennese compositions, "Sóra Paradìxo" by Ciro Nenci is in the masimalista style. The 18th century saw a return to more minimalist compositions by composers such as Eliodoro Mariani, Mileno Trapani and Roseƚa Adesso.

Contemporary Navennese music emerged in the middle of the 20th century, with pop and rock acts influenced primarily by Plevian and Ingerish music. Many artists sought after international appeal and thus many artists write songs in languages other than Navennese, primarily Ingerish and Plevian. Navenna was an important nation for disco in the 70s. Navennese disco music evolved into its own genre known as Navennodance in the late 80s, which is characterized by its faster tempo and futuristic sound. Navennodance acts such as Fanfara, EONS and Alfio Amantea saw international success in the 80s and 90s. The 1990s saw the emergence of Navennese language rap and hip hop in the urban centers in the south. Navennese hip hop takes influences partly from Ingerish language hip hop, but has strong roots in immigrant communities in Navenna with Turquese and Mardoumakhi influences.

Navennese companies have been instrumental in the development of electronic music hardware. As such, contemporary Navennese music is known for its early adoption and widespread use of electronic elements, such as synthesizers, drum machines and vocoders. Another important aspect of contemporary Navennese music is the country's rave culture which emerged in the 80s following a liberalization of recreational drug use. The 90s saw the rise of Navennese electronic dance music, notably Ƚo-Trance originating from Ƚovana, and Navennese hardcore drawing influences from Lentian gabber and Ingerish drum & bass. Today, electronic dance music is not confined to raves and clubs, but are part of mainstream Navennese music culture. Many electronic music festivals are arranged in Navenna, attracting arists from all over the world. Later developments in Navennese electronic dance music include hardstyle, house and industrial hardcore. Popular Navennese electronic dance acts include Sacagnàda, Sótovóxe, Stargazer, Ƚoris Ventura, Bruna Armati and Pharix. The former industrial towns Meletta and Seƚi are known for their experimental electronic music scenes which developed during the early 2000s, utilizing unorthodox samples and exotic sound design techniques.

Cuisine

Navennese cuisine has a long and rich history, having integrated elements of cuisines from neighboring cultures, primarily from Plevia, while maintaining a distinct Navennese identity. Navennese gastronomic culture is usually divided into two main geographical regions which have affected what ingredients are available, what cooking techniques are used, and which other cultures have had an influence. Cuisine from the coastal regions of Navenna is rich in seafood, beef and wheat, while the cuisine of the interior regions of Navenna are to a greater degree based around poultry, lamb, mushrooms and vegetables. Historically, game meat has been an important protein source in remote and mountainous regions, and is still incorporated into some local delicacies. While regional differences have diminished greatly in modern times, with most dishes being available anywhere in the country, some local variation still exist, especially for cheeses and cold cuts since many local variants enjoy a protected origin under Navennese law.

Meal structure

Meal structure in Navenna is similar to the standard southwest Ulethan meal structure, but with some distinctive features. Notably, the three larger meals of the day, breakfast (coƚasión), lunch (disnàr) and supper (zséna), are usually eaten a few hours later than what is typical in other Ulethan countries.

Breakfast usually involves smaller portions and has a larger emphasis on sweet dishes rather than savory dishes. Breakfast is traditionally served with baked goods like biscuits or bread such as fiƚón or Plevian ciabatta. Slices of bread are usually spread with butter or jam, and more recently, chocolate spreads. Seasonal fruits and berries are a common side in breakfast. Occasionally breakfast include pastries, such as briozsiò or sfoƚiatela. Meals are eaten together with coffee, tea or milk. Fruit juices are not prt of the traditional Navennese breakfast but have become more common in modern times. Sometimes breakfast is omitted entirely, and is substituted with a larger late-morning meal known as ùndexenette, similar to elevenses or brunch. Ùndexenette can include more savory dishes in addition to traditional breakfast dishes, with a larger emphasis on cold cuts, salami, cheeses and seasonal vegetables.

Lunch is considered the most important meal of the day; outside of special holidays it is also the largest meal. The common everyday lunch usually consists of only one or two courses, but can consist of up to five courses during special occasions. Meats, pasta, bread and fresh vegetables are common ingredients in Navennese lunch meals. While lunch usually has an emphasis on hot meals, it is a common custom in Navenna to have a cold course during hot summer days. Lunch is traditionally served with wine, cider or sparkling water. Supper in Navenna is relatively light, rarely consisting of more than one course. The exception is during holidays, where supper is usually the most important meal of the day, following the same meal structure as a full lunch.

Ingredients

Pasta forms the staple food of Navennese cuisine, typically made with wheat flower and egg. Stuffed variants such as rafióƚo and tortèƚi are especially common, usually with a meat, vegetable or cheese-based filling. Bread is another staple in Navennese cuisine, with a multitude of local bread variants. Fiƚónis a traditional yeast-leavened bread, and is the most common everyday bread. Tomatoes, peppers, onions, olives, cabbages, artichokes, garlic, eggplants, broccoli, asparagus and zucchini are commonly used ingredients in Navennese dishes. Olive oil is widely used, both as a cooking fat and as a base for sauces. A common Navennese sauce is rùxene made with egg yolk, olive oil, garlic, lemon and chilli peppers (pevarónsini). Dishes are commonly spiced using black pepper, pevarónsini, parsley, chives and basil. Due to Navenna's history as a maritime republic with extensive trade networks, the country has enjoyed prolonged access to many exotic herbs and spices such as vanilla, cocoa and ginger which have historically been used in upper-class dishes. Peppers have since their introduction in the country become a staple ingredient, adding heat to many Navennese dishes.

Making cheese from cow, sheep or goat milk is an old tradition in Navenna, with a plethora of cheese varieties having been developed over time. Many Navennese cheese varieties have been exported and adapted abroad. Some notable cheese varieties include maseƚo, a soft cow's milk cheese named after its traditional point of origin, the town of Maseƚo; marxa fatisènte, a hard granular cow's milk cheese originating from Seƚi; sviƚéte, a semi-soft blue-veined cheese; and sanguinóxo Navennato, colloquially known as Navennese blood cheese, a hard delicacy cheese colored and flavored with red pesto.

Seafood has an elevated status in Navennese cuisine. Sea bass, sea bream, swordfish and tuna are common in traditional recipes, and Navennese supermarkets usually stock imported fish such as cod, haddock and salmon. Cuttlefish and squid are considered delicacies in Navenna, and squid ink is sometimes integrated into dishes. The most notable seafood delicacy is crùo, consisting of thinly sliced or diced raw fish usually served with vegetables and bread.

Dishes

Navennese dishes are generally simple in preparation, with an emphasis on fresh, high quality ingredients rather than complex techniques for preparation. Notable foods include:

- Crùo - an iconic dish from Navenna Lagunare, it consists of thinly sliced or diced raw seafood meats, typically tuna, shrimp, cuttlefish, octopus and salmon. Crùo is served as an antipasto on its own, or as a main course together with vegetables, bread and soup. Originally a delicacy reserved for the wealthy or only eaten during festivities, crùo is now widely available at restaurants specialized in preparing crùo dishes, and is served in a multitude of ways. Crùo is commonly compared to sashimi.

- Rafióƚo - stuffed pasta served with a variety of fillings, such as cheese, sage, onion, spinach, and poultry or beef meat. The pasta is served in broth or with a sauce.

- Supìn d'ingiòstro (lit: "ink soup") - a fish soup made primarily with cuttlefish and squid, occasionally combined with crabs and mussels. Its name comes from the fact that the soup is colored dark using squid ink. The soup is commonly served with rùxene and bread.

- Pasta aƚa pevaràsa - pasta served with clams, tomatoes and garlic, usually served with a sauce prepared with olive oil, pevarónsini, black pepper and white wine. Occasionally cheese is added.

- Bixàto frito - fried eel, a typical dish in Anoria.

- Manxo mirúno - a beef stew originating from Mirùn, typically prepared with onion, garlic, mushrooms and red wine.

- Foods of Navenna

-

Crùo

-

Pasta aƚa pevaràsa

-

Manxo mirúno

-

Rafióƚo

-

Supìn d'ingiòstro

-

Bixàto frito

-

Slices of fiƚón

-

Rùxene

Navenna has a long tradition of making desserts and pastries. Laminated dough, a technique originally brought to Navenna by merchants have become a speciality among Navennese bakers. Notable baked goods and desserts include:

- Sfoƚiatela - a shell-shaped layered pastry, made with various fillings such as jam, vanilla custard or chocolate cream.

- Briozsiò - a buttery and flaky pastry made from a yeast-leavened laminated dough, similar to Valonian croissants but more compact.

- Tiramisù - a layered mocha-flavored cake.

- Bussolà - lightly lemon-flavored and buttery cookies from Migia.

- Fritoƚe - small, round fried doughnuts sprinkled with sugar and occasionally filled with fruit, custard or chocolate.

- Sorbetto - a frozen dessert with Turquese origins, made from frozen fruit juice, purée and wine, and sweetened with sugar or honey. Typically served with berries or with Plevian gelato.

- Nocolàt∈⊾ƨ - a hazelnut and cocoa spread commonly used as an ingredient or topping for various desserts. Originally from Mirùn, it is now produced in various locations around the world.

- Desserts of Navenna

-

Sfoƚiatela

-

Briozsiò

-

Tiramisù

-

Fritoƚe

-

Sorbetto

-

Nocolàt on a slice of bread

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tamborello, E., Di Noto, L., Filipi, A. & Rubbo, G. (2015). Dark Money: Exploring The Offshore Financial Centres of The Global East. Ulethan Financial Studies, 16(5), pp. 233-265. UUI: UX-091:18261001018

- ↑ "Navenna named as 5th worst tax haven in the world". Presses Generaux. 17 June 2017.

- ↑ ASUNACB (2020). Report: Multinational Tax Schemes of Navenna.

- ↑ Galo, F; Nissa, J & Cabrese, L. (2015). Soil Quality and Capacity for Population Growth in Anoria, Navenna. Effesian Agrology Journal, 15(2), pp. 1077-1102. UUI: SE-212:928328004329

- ↑ Hájek, T & Riley, H. (2009). Post-industrial Recovery and Apadtation: A Case Study of Post-industrial Economies in West Uletha. Human Geography Review, 22(1), pp. 805-822. UUI: RR-231:09128122106

- ↑ NavStat (2020). Ano in rasegnà - Infrastruttura è strapòrto 2020. Navenna: NavStat.

- ↑ Ministry of Health of Navenna (2018). http://www.minsn.na/en/sicurasion Retrieved 3 March 2019.

| Infrastructure • View on map | |

| Neighbors | |

|---|---|

| Membership | Association of South Ulethan Nations |

| Global topics | Airports • Businesses • Currencies • Driving side • Electricity • Intergovernmental organizations • Languages • Rail transport |