Izaland

|

Republic of Izaland  華邦共和國 Izaki Kyohwakuku (Izaki) Capital: Sainðaul

Population: 117,732,119 (2023) Motto: 天પ દૅપ્યા、民પ દૅપ્યા、પતે 団結ઠૅડાપ્પૅ。/ Asunan renshi, wikerin renshi, nahu dankes tokinne. (For heaven, for the people, we are united) Anthem: / 國પેતૅ、天પ 下ટ。/ Askazhinuhe, asunan kauris. (Our country, below the Heaven) |

Loading map... |

The Republic of Izaland (華邦共和國, Izaki Kyohwakuku), commonly referred to as Izaland, is a country in southeast Uletha. Spanning 308,513.11 km², Izaland also includes the island of Kubori, which makes up around 20 % of the country's landmass. Izaland borders Belphenia and Nuen to the east; Federal Republic of Wendmark-Ðenkuku, Saikyel, and Blönland to the north; and Pyeokchin to the west. Kubori Island faces the Sound of Pa in the southern part of the country`, and shares marine borders with Ugawa.

The country's capital is Sainðaul (also spelled Saindzaul), located across the Tandan Strait, with other major cities including Kichatsura, Panaireki and Warohan on Kubori, and Riyatoma and Sannupuri on the country's continental area. With nearly 118 million inhabitants, Izaland is one of the most densely populated nations.

Ever since its economic boom following the Great War, Izaland is one of the world's most economically advanced nations with high standards of living and wealth. Its economy has traditionally been driven by the manufacturing, agriculture and technology sectors, although it has recently expanded into the communications, services, finance, and tourism sectors. Izaland is ranked highly in terms of civil liberties, healthcare, and human development.

In Izaki (romanised): 👂 listen recording here

Izaki kyohwakuku, tsōntsī Izaki (ēngurigounde Izaland), dōnnan-Urezhūs seyoittu askashi yora. Izaki, Kubori-haman ðennyukun (iko myensheku ðenkukudo 308.131,36 km2(tāski kilometuri)s juitte yaku 20% yori) suma, Urezhū tairikin dōnnanbum ispunū kakuera. Izagin shuto, Tandan kaikyō toeyake Sainðaul yotte, daini toshi nanbun paikuke Warohan yora. Izagin rinkukuinkai, shikisangan Saiki, Bonlanti ta UL28h, narisangan Belfenya ta Nuen, nijisangan Pekutsin, sebunte otsumisangan Pākutō yorahan.

Zhinkumisto 1 tāski kilometuri noilke 385 zhin yotte, sōnzhinkwankai yaku 1 oku 1800 man zhinnin idaryera. Juminen daibubun shutokwennes ta Warohannas, Panairegis, Kichatsuras kihtoken Kubori-haman saibus yohan nazae ōdahan toshiis paera. Nazae juyo tan toshibūn, juwon dairikus onomattuhan Riyatoma ta Makkenoke, epakoente Sainðaullul yaku 100 km nantanke yon Isadashi, sebunte Volta-hannan yon tsaidain sāreotoka, Sannupuri yorahan.

Izaki taichensō riyattu keiðaiseichānki irai, rihan seikwas suijun ta rikusū nuleke sekais keiðaichekes ichattu hankuku yora. Izagis keiðai ponlai cheizhonnwya, nōwya, gizhus pumunnul gennin taki kade, tekkayase tsaikin se, tsōnshin, pāpelu, kinnyūn, kwankwō pumuner ri ōdaneshissan yora. Izaki shiminen jiyu, wiryō, zhinkankaipassan nuzhisli rihan pyokā adekara.

'華邦'共和國, 通称 華邦 (𖬒ɭ։ᐢ𖬭𖬰𐐢𖬬𖭐語𖬒𐐢ᐢ𖬣𖬰ɭ Izaland), 東南宇礼洲ᒢ 於ꓩ𖬮𖬒𖭐フ𖬣𐐢 國 ꓩ𖬮𖬬. 華邦, 久保里島ᐢ 全域ᐢ (全 面積 全國土 308.131,36 km2(𖬣։ᒢ𖬭𖭐 𖬭𖭐𖬈ᐤ𖬊ɭ𖬣𐐢𖬬𖭐)ᒢ 中フ𖬣ɭ 約 20% ꓩ𖬮𖬬𖭐) 𖬖𐐢𖬊, 宇礼洲 大陸ᐢ 東南部ᐢ 一部𖬒𐐢 占𖬒ɭ𖬬. 華邦ᐢ 首都, 丹淡 海峡 跨𝖩𖬮𖬭ɭ 作安崎 ꓩ𖬮フ𖬣ɭ, 第二都市 南部ᐢ 置𖬭𐐢𖬭ɭ 深彎 ꓩ𖬮𖬬. 華邦ᐢ 隣國𖬒𖭐ᐢ𖬭ᐟ𖭐, 北側ᒢ 斎喜, 𖬡𖬰ᐤᐢ𖬈ᐢ𖬣𖭐 𖬣 𖬒𐐢ᐡ28ᐪ, 東側ᒢ 𖬡𖬰ɭᐡ𖬔ɭ𝖩𖭑 𖬣 𖭑ᥫᐢ, 西側ᒢ 壁珍, 了ᐢ𖬣ɭ 南側ᒢ 波亜海 ꓩ𖬮𖬬𖬨ᐢ.

人口密度 1 𖬣։ᒢ𖬭𖭐 𖬭𖭐𖬈ᐤ𖬊ɭ𖬣𐐢𖬬𖭐 𖭑ᐤ𖭐ᐡ𖬭ɭ 385 人 ꓩ𖬮フ𖬣ɭ, 総人口𖬒ᐢ𖬭ᐟ𖭐 約 1 億 1800 萬 人𖭑𖭐ᐢ 至ꓶ𖬬𖬬. 住民𖬒ɭᐢ 大部分 首都圏𖭑ɭᒢ 𖬣 深彎𖭑ᒢ, 若浦ᒢ, 亀茶汐ᒢ 𖬭𖭐ᐪ𖬣ᐤ𖬭ɭᐢ 久保里島ᐢ 西側ᒢ ꓩ𖬮𖬨ᐢ 𖭑𖬖𖬰ᐟɭ 大𖬨ᐢ 都市𖬒𖭐ᒢ 住𖬒ɭ𖬬. 𖭑𖬖𖬰ᐟɭ 主要𖬣ᐢ 都市部𖬒𐐢ᐢ, 中央 大陸ᒢ 當𖬊フ𖬣𐐢𖬨ᐢ 追庥 𖬣 平坂, 加𖬒ɭᐢ𖬣ɭ 作安崎𖬈𐐢ᐡ 約100 km 遠𖬣ᐢ𖬭ɭ ꓩ𖬮ᐢ 安村, 了ᐢ𖬣ɭ 𖬔𖬰ᐤᐡ𖬣-彎𖭑ᐢ ꓩ𖬮ᐢ 最大 港町, 乾山 ꓩ𖬮𖬬𖬨ᐢ.

華邦 大戦争 𖬬𖭐𝖩𖬮フ𖬣𐐢 經濟成長期 以来, 高ᐢ 生活水準 𖬣 富𖬖𐐢։ 𖭑𐐢𖬈ɭ𖬭ɭ 世界ᒢ 經濟的ᒢ 𖬒𖭐𖬥フ𖬣𐐢 一國ꓩ𖬮𖬬. 華邦ᒢ 經濟 本来 製造業, 農業, 技術 部門𖭑𐐢ᐡ 牽引 𖬣𖬭𖭐 𖬭𖬣𖬰ɭ, 𖬣ɭフ𖬭𝖩𖬮𖬖ɭ 最近 𖬖ɭ, 通信, 𖬡։𖬡ɭ𖬈𐐢, 金融, 觀光 部門𖬒ɭᣗ 𖬬𖭐 大𖬣𖬰𖭑ɭ𖬧𖭐フ𖬧ᐢ ꓩ𖬮𖬬. 華邦 市民𖬒ɭᐢ 自由, 醫療, 人間開發𖬖ᐢ 𖭑𐐢𖬧𖬰𖭐ᒢ𖬈𖭐 高ᐢ 評価։ 𖬒𖬣𖬰ɭ𖬭𖬬.

History

Prehistory

| History of Izaland | |

|---|---|

| Kōmun Era 甲文時代) | until year 75 AD |

| Busshō Era 仏照時代 | 75 - 453 |

| Kanaskashi Era 二國時代 | 453 - 1178 |

Izaland is believed to have been settled since 50,000 BC, with migrations of settlers from western Uletha. The presence of tall mountain ranges in the central-northern part of the territory has meant that, until relatively modern times, the contacts between the populations of the north, and those of the south, were sporadic, and limited to feeble commercial exchanges.

The earliest populations were initially hunters and gatherers, and tended to settle along the great rivers of the central highlands, which offered environments rich in provisions and able to allow the continuity of the first communities. Often it was a matter of nomadic aggregations, which moved together with the animals that allowed their sustenance. The first agricultural techniques, spread from the west around the 13th century BC, allowed the improvement of the yield of crops, and the trade in rice, soybeans and other cereals led to the birth of the first cities and the first semi-organized communities.

The first urban centers in the north of the country were governed by a central family, who managed the administration relying on a series of senior councilors, as well as seers (called akeru, or ikoru), often represented by the elderly women of the village, who were believed were closest to the gods and spirits of nature.

A system in force in present-day western Izaland was that of the rindokareri in which a certain number of advisers and seers were exchanged between some allied villages, with the aim of providing more genuine data and predictions unrelated to possible elements of corruption or favors to certain inhabitants of a village.

1st to 8th century - The prominence of Illashun and Sopeke kingdoms

Around the year 0 the territory that currently corresponds to Izaland was divided into a large number of small non-centralized entities, with the exception of two kingdoms that were gradually starting to stand out in the local landscape: the Kingdom of Illashun (院良春王國), with its center in the current city of Illashiya), and the Kingdom of Sopeke (岨坪畍王國), located where the prefectures of Riyatoma and Makkenoke are now located, in the center of the continental area of Izaland.

The first trade between the two nations began to develop starting from the year 75 AD, when some inscriptions found in the historical site of Haketono (横榁) suggest that the diplomatic mission by Prince Kukeyatan Urevi had taken place who, from Illashun, went with a mighty escort, exploring to the north. This allowed the Illashun Kingdom to establish the first diplomatic relations with King Tainal II of Sopeke.

The two kingdoms experienced a certain period of peaceful coexistence and the main products of exchange were amber from the north and food products from the south.

However, around the 2nd century AD, traders from the Kyowan homeland and the Meng Kingdom (孟朝, Mēn in Izaki - odiern Peichew Empire) started to establish trading ports and coastal towns on the Ashin (Axian) Peninsula, resulting in strong Huaxian and Kyowan influences on the local cultures. After the Great Unification between the kingdoms of Illashun and Sopeke (232 AD) , the newly established Kingdom of Sopeshun (岨坪春王國) rose into prominence around the 3rd century AD, and dominated most of Kubori Island and the Izaki mainland until its weakening in the 8th century. The Sopeshun Kingdom attempted several times to subdue the southern Kubori tribes to secure control of the coastal ports; the tribes instead unified to establish the rival Ipseris Federation that would remain outside Sopeshun control. With the fragmentation of the Sopeshun Kingdom, the Kubori King launched its conquests over the Izaki mainland.

The Ðenzhū era

The Ðenzhū Era (煎宙時代, 768-1312) is one of the most transformative periods in Izaland's history, marked by political consolidation, territorial expansion, cultural reforms, foreign relations, and religious evolution. Below is an expanded overview of the period, incorporating the reigns of key monarchs, major events, and broader socio-political themes.

The Beginning of the Ðenzhū Era (768-804)

King Urekin (Ipseris Family)

- The reign of King Urekin marked the foundation of the Ðenzhū Era (煎宙時代) and a period of unprecedented territorial expansion.

- Capital Relocation to Illashiya (769): The move from the previous capital (from Warohan) to Illashiya symbolized a shift in administrative focus and provided a strategic location for the growing kingdom.

- Territorial Holdings: At its height, the Kingdom of Ipseris (or Isseris) controlled all of Kubori Island, most of the mainland (modern Izaland), eastern Pyeokchin, Nuen, Ugawa, the Kyōwa Peninsula, and the AR920 islands. This established Izaland as a regional power.

- King Urekin's reign was characterized by efforts to centralize the administration and manage such a vast territory.

Expansion and Consolidation (804-878)

- King Urekin II (804-818): His reign was marred by personal tragedy, as he succumbed to tuberculosis. However, administrative stability continued.

- King Saikamuta I (818-856): A steady reign with efforts to strengthen the kingdom's defenses and stabilize relations with neighboring powers, including the newborn Fu dynasty in Northern Archanta (nowadays Huaxia).

- Plague Outbreak (856-860): A devastating plague, referred to as the "Hekushiyekk" (黒死疫) caused the deaths of approximately 450,000 people, disrupting economic and social structures.

- King Saikamuta II (856-857): His brief reign ended with his death during the plague, plunging the kingdom into uncertainty.

- King Saikamuta III (857-878):

- Reishoki Reform (令書紀改新): Inspired by similar reforms in the Huaxian Fu, these changes restructured governance, centralizing power under the monarchy and introducing a more efficient taxation and military system.

- Codification of Laws: The reforms also emphasized codifying laws to strengthen the authority of the central government. This period marks the rise of a bureaucratic class.

The Golden Age and External Challenges (878-1037)

- Queen Hariken Samashi (878-911):

- A rare female ruler, Queen Hariken oversaw the Battle of Miuro, securing Izaland's dominance in the southern territories. Her reign is seen as a time of relative prosperity and stability

The Battle of Miuro: A Turning Point in Izaland’s History

The Battle of Miuro (883) marked a critical moment in Izaland’s history, showcasing its military and diplomatic prowess under the leadership of Queen Hariken Samashi. At 38, Hariken was already known as a shrewd and capable ruler, but the alliance between the Kyōwan Empire and the small yet strategic kingdom of Miuro threatened Izaland’s dominance in the southern Ardentic Ocean.

When the Kyōwan fleet blockaded Miuro’s ports, Hariken devised a bold strategy with her advisors. Izaland’s smaller but faster navy would slip past the blockade at night to launch a surprise attack, while General Makaji Yues led a ground assault on Miuro’s capital to force King Chinpafaa to surrender before Kyōwa reinforcements arrived. The operation commenced with careful precision. Izaland’s fleet successfully navigated past the Kyōwan blockade under the cover of darkness. However, by dawn, the Kyōwa fleet detected the maneuver, leading to a fierce naval engagement. Hariken, according to historical records, personally commanded from her flagship, the Golden Tempest (金嵐, Kinlan), which became a focal point of the battle. While the naval conflict unfolded, General Yues and his forces breached Miuro’s defenses, and King Chinpafaa surrendered. Deprived of support, the Kyōwa fleet retreated.

To secure peace, Izaland demanded access to Nagaiso Port, which Emperor Daishū accepted in exchange for halting further hostilities. While some historians argue Queen Hariken may not have been physically present during the battle, her leadership during this pivotal moment is unquestionable. The victory solidified Izaland’s regional influence and is remembered as a turning point in its history. Queen Hariken remains a celebrated figure, often depicted in historical dramas as a symbol of courage and strategic brilliance.

- King Chikahome I (911-965): Continued to develop the kingdom’s infrastructure and defenses.

- King Chikahome II (965-1002):

- The northern Alvidian Invasions in 987, 989, and 996 severely challenged Izaland’s authority, leading to the occupation of the Dōnpuku Region and Nuen. These invasions marked one of the kingdom’s darkest periods.

- King Chikahome III (1002-1037):

- Battle of Kyuoi (1015): A significant military victory that allowed Izaland to reconquer territories lost to the Alvidians and expand into Ankwoen. This battle was a turning point in the kingdom's resurgence.

Cultural Flourishing and Religious Transformation (1037-1139)

- Queen Shihan (1037-1061):

- Diplomatic Relations with the Rō Kingdom (Kojo): Initiated cultural and trade exchanges, which introduced Symvanism (a prominent religion originating in Kojo). The religion began to influence Izaland’s spiritual landscape.

- King Teibaru I (1061-1079): Continued fostering cultural ties and internal development.

- King Hansura I (1079-1096):

- His marriage to Princess Huang Feng of Peichew symbolizes the strengthening ties between Izaland and Peichew, or more broadly, Huaxia.

- Kings Hansura Huang II and III (1096-1139):

- The Second Alvidian Invasion (1125-1127): Although Izaland managed to resist the invasion, the kingdom lost Ankwoen once again.

Rise of Dharmapala and Architectural Achievements (1139-1188)

- King Teibaru II (1139-1164):

- State Religion: Dharmapala was declared the official state religion. Temples and religious centers became central to Izaland's cultural identity.

- Temple Construction: Sumptuous Dharmapali temples were constructed across the kingdom, some of which still stand as symbols of the era.

- King Teibaru III (1164-1188):

- Royal Palace of Illashiya: The construction of the Royal Palace was completed, solidifying Illashiya's status as the cultural and administrative heart of the kingdom.

The Awangusain Dynasty and Centralization of Power (1188-1290)

- King Reno I (1188-1208): Founded the Awangusain Dynasty, ushering in a period of centralized rule.

- King Reno II (1208-1248):

- Rebellion in Itakiri Province (1236-1237): The rebellion was swiftly crushed, showcasing the dynasty’s military strength and ability to maintain control.

- Expansion in Zhenkuku Region: This expansion further solidified the dynasty’s influence.

- King Reno III (1248-1290):

- Kyentei Law (1256): Established the framework for the transition of the kingdom into an empire. The law centralized imperial authority and formalized the emperor’s divine status.

The Formation of the Empire and Division (1290-1312)

- Emperor Takamuta I (1290-1325):

- Sanbakai Conflict (三馬懐紛争, 1298-1302): A prolonged conflict that divided the empire into factions. The Kubori islanders began to rebel against the Awangusain government due to opposition to increased taxation and the empire's failures to address the repeated floods and droughts. The merchants of the Peichew Soh Dynasty took this opportunity to aid the rebels and overthrow the Awangusain Kingdom and, in 1302, Takihasu Mitsuburi, an eminent merchant originally from the Itakiri archipelago, enriched by his trading fleets which had contributed to bringing wealth both to the coffers of Awangusain and to those of other trading partners in the region, with his skilled diplomacy he obtained the role as a regional inspector for the southern part of Kubori from the Soh Dynasty. In 1312 he obtained the title of King, and took the name of King Chōdae I (朝廼一世). Ultimately, the emperor was forced to flee to Kansāri (near Riyatoma), establishing a new capital on the site of a prominent Buddhist center.

- The conflict weakened central authority and marked the beginning of the decline of the unified Izaki Empire.

Establishment of the Kingdom of Kubori (1302-1334)

- In 1302, the western territories (including Kubori Island and surrounding regions) declared independence, forming the Kingdom of Nakai under King Chōdai I (趙廼一世). This effectively ended the Ðenzhū Era and marked the fragmentation of the Izalandic Empire.

Key Themes of the Ðenzhū Era

- Territorial Expansion and Contraction: The era saw Izaland's greatest territorial extent, followed by challenges from external invaders (notably the Alvidians) and internal divisions.

- Cultural and Religious Transformation: The introduction of Symvanism and the establishment of Buddhism as the state religion shaped Izaland's cultural identity.

- Reforms and Centralization: The Reishoki Reform and Kyentei Law laid the foundation for centralized imperial authority.

- Foreign Relations: Diplomatic ties with Huaxia's Suo dynasty, Kyōwa and Kojo brought cultural exchange, technological advances, and stability.

- Architectural Achievements: The construction of temples and the Royal Palace of Illashiya reflected the kingdom's prosperity and commitment to Buddhism.

Late Medieval Period (13th century – early 17th century): The Nakai Kingdom and the Rise of Izaki Power

Foundation and Bai Influence

Following the collapse of the Soh dynasty and the weakening of Bai power in the region during the 13th century, the coastal regions of what would become modern-day Izaland entered a new phase of semi-independence under the Nakai Kingdom (奈堺王國). Named after the royal palace in Warohan, the Nakai Kingdom functioned initially as a Bai protectorate, with Bai merchants and officials maintaining concessions in key port cities including Warohan, Daishin, Kanlisahna, Illashiya and Kokendake (now part of modern-day Sainðaul). These cities became thriving hubs of maritime trade, shipbuilding, and military outposts as Bai influence spread throughout the southern Axian coastlines.

After the official fall of the Bai Empire in 1299 following internal rifts and the weakening of Kyōwa’s regional hegemony, the Nakai Kingdom began to exercise de facto sovereignty, although it remained bound by complex trade and tribute obligations to various external powers, including the Soh dinasty of Pewchew. Around this time, the kingdom began referring to itself more formally as the Kingdom of Izaki (華𡈁)—though in Ingerish, the simplified exonym “Izak” was more commonly used. The current term Izaland would not emerge until the 20th century.

The Twin Courts War (1384–1411)

In 1384, a dynastic crisis emerged following the sudden death of King Kinlei II without a direct heir. Two rival factions of the royal family claimed the throne, leading to a protracted civil conflict known as the Twin Courts War (雙朝之亂, Soinchō no Ran). The two factions—the Shinlen clan (信憐班) based in Illashiya (the former administrative capital of the central-northern provinces), and the Darenoko clan (樋偭班), which controlled the coastal strongholds around Kanlisahna and Daishin—established rival courts and fought for supremacy.

The conflict lasted nearly three decades, causing widespread disruption to trade and governance. The Darenoko court gained early momentum due to stronger naval access and external trade backing, but ultimately the war was resolved through a marriage alliance brokered in 1411 and a strategic compromise on royal succession.

The Nahan War and the Birth of a Unified Crown (1548–1553)

Rivalries between the Awangusain Kingdom on the continental side and the Nakai Kingdom on Kubori Island culminated in the Nahan War (〇〇戦争). After five years of intense naval and land battles, the conflict ended with Nakai’s decisive victory under King Jinlwi I, who proclaimed the unification of the two realms. This event marked the first true political integration of the Izaki people across the Tandan Strait, laying the foundations for a centralized kingdom.

The war also prompted significant military reforms, including the creation of a permanent naval force headquartered on Kubori’s southern coast, which would later underpin Izaland’s maritime ambitions.

Maritime Expansion and Overseas Ambitions (1430–1650)

Izaland’s first overseas ventures began not with triumph but with tragedy. In 1432, shortly after the consolidation of the Nakai and Awangusain realms, the newly unified Izaki state sought to expand southward toward the rich trading ports of Teluktebu—a tropical region known for its spices, gold, and exotic woods. A fleet of over forty ships was dispatched to establish contact and claim the coast.

However, in 1433, while crossing the Gaforu Strait, the expedition was struck by a violent typhoon. The catastrophe—later immortalized as the “Night of the Broken Sails” (砕帆之夜, Swaihannan niska)—destroyed most of the fleet, leaving hundreds dead and the survivors shipwrecked on hostile shores. Captured by Majesian pirates, the survivors were imprisoned for nearly two years until a diplomatic mission in 1435 secured their release.

The disaster deeply scarred the national memory but also triggered a new era of naval reform: Izaki shipwrights began developing reinforced hulls, double-keel vessels, and standardized maritime codes that laid the foundations for later expansion.

Over the following two centuries, Izaki mariners continued to explore the southern seas, learning from successive failures. By the early 17th century, under King Shaihari II, the crown established the South Sea Trading Company (南陽貿易会社, Nannyān Mauyeku Kwisha), formalizing state-sponsored overseas enterprise.

In 1615, the Company successfully founded a permanent trading post at Ribochanja and opened the Free Port of Shinkō (新港) along the coast of Teluktebu, today known as Equatorial Izaland.

At that time, Teluktebu was inhabited by Majesian-Central Archantan peoples and governed by the Imani Caliphate, a successor to the ancient Majesian Kingdom. Initially a small enclave for spice and gold trade, the Izaki outpost gradually expanded into a thriving commercial colony governed jointly by Company officials and royal commissioners.

By the mid-17th century, Equatorial Izaland had become a vital node in Izaland’s growing transoceanic network, linking Sainðaul, Suvuma, and Bai with the wider Archantan basin. Despite setbacks such as the Ingerish–Izaki conflicts of the 1640s over Banfin, Izaland’s southern ventures marked the birth of its maritime empire and the dawn of its modern identity as a seafaring nation.

Conflict and Rivalry with Kyōwa and the Conquest of Banfin

Following a weak period for Soh, Izaki turned its ambitions northward and westward, seeking to dominate maritime routes in direct competition with Kyōwa, its former overlord. Both powers vied for influence in the fragmented territories of the former Soh Empire, including the culturally significant region now known as Banfin (汳濱)—later renamed Belphenia by Ingerish colonists in the 17th century.

Throughout the late 16th century, a combination of military expeditions, naval skirmishes, and strategic marriages brought large parts of Banfin under Izaki control, though the competition with Kyōwa remained fierce for much of the century.

Legal and Cultural Reforms

In 1495, King Teiran introduced a series of political and ethical reforms to centralize administration and reinforce royal authority. Known as the Twelve Precepts of Governance (治國十二誡, Chikuku Shūnikai), these reforms blended classical Hanuist philosophy with administrative principles influenced by Kalmish legalism. The precepts outlined codes of ethical conduct, governance structures, and procedures for resolving internal disputes. They later became the basis for the civil service examination system in early modern Izaland.

Founding of Hwakaku University

In 1512, the crown established Hwakaku University (華鶴院, Hwakakuwin) in Kanlisahna as an elite institution intended to educate the sons of nobility and upper-class merchants in law, diplomacy, philosophy, and foreign languages. Drawing inspiration from both Axian and Ulethan models, Hwakaku played a pivotal role in shaping Izaki bureaucratic culture and produced many of the key statesmen of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Court Intrigue: The Perfumed Cup Incident (1571)

The Perfumed Cup Incident (香杯之事, Kyāmpain Te) was one of the most notorious court intrigues in late Nakai history. In 1571, Queen Saiyuna, consort to King Jinlwi, was assassinated under mysterious circumstances after publicly opposing a secret trade pact with Kyōwa merchant guilds. The incident led to an extensive purge of court officials suspected of treason, deeply fracturing the aristocracy and becoming the subject of numerous plays and operas throughout the early modern period.

Legacy of the Nakai Kingdom

By the early 17th century, the Kingdom of Izaki had emerged as a powerful and culturally hybridized state, blending native traditions with influences from Lin (Peichew), Kalmish, and Western Ulethan sources. Its control of Equatorial Izaland and some routes to Suvuma allowed it to dominate the regional spice and resource trade, with goods such as vanilla, tobacco, cacao, and coffee forming the basis of a growing merchant empire.

At the same time, increasing exposure to Ulethan powers would set the stage for both cultural flourishing and later colonial tensions—marking the end of the Nakai era and the dawn of modern Izaki identity.

The Belphenian Conflict and Treaty of Taemoigon (1643–1651)

With Ingerish colonists establishing settlements in Banfin (Belphenia), tensions with Izaki garrisons led to several naval engagements and skirmishes around ??? Bay and ???.

The conflict concluded with the Treaty of Taemoigon (1651), which recognized Ingerish control over Belphenia’s western coast while confirming Izaland’s sovereignty over its existing colonies and territories. Although a diplomatic concession, the treaty allowed Izaland to consolidate its maritime sphere elsewhere, particularly in Equatorial Izaland and trade with Suvuma.

The Reign of Queen Marune the Giantess (1650–1668)

Queen Marune, notable for her height (182 cm), ruled during a period of consolidation and cultural flourishing. She reinforced Izaki authority across the Tandan Strait, strengthened the southern ports of Warohan and Daishin, and oversaw the expansion of maritime trade routes. Her reign was marked by both political stability and the early formation of an intellectual elite, fostering developments in navigation, philosophy, and medicine.

Semi-Autarchy and Internal Development (1690–1750)

Although Izaland never fully closed its ports like Kyōwa’s sakoku, it entered a period of relative autarchy. Trade was limited to licensed ports—Shinkō, Sainðaul, and Warohan—and the crown focused on stabilizing internal administration and resource exploitation.

This period saw:

- Expansion of irrigation networks and improved road infrastructure.

- Development of coastal workshops and inland proto-industrial centers.

- Strengthening of naval and merchant fleets, ensuring the kingdom’s dominance in regional waters.

Proto-Industrialization and Social Tensions (1750–1830)

After the long period of autarchic consolidation that followed the decline of overseas ventures, Izaland entered a new age of domestic transformation. The late 18th century saw the gradual mechanization of textile production in Makkenoke, Daishin, and the river valleys north of Sainðaul, where abundant coal and timber provided the resources necessary for industrial growth. What had begun as small guild-based workshops evolved into larger manufactories powered by waterwheels and early steam engines imported through limited trade with the Kalmish and Alvedic merchants of the Gulf of Volta.

This early industrial activity marked a fundamental shift in Izaland’s social fabric. The once-dominant landowning aristocracy, weakened by decades of maritime decline, found its influence challenged by a rising mercantile class centered in the southern port cities. Meanwhile, the rural population, displaced by agricultural reforms and the concentration of estates, began migrating toward urban centers in search of work. These demographic pressures gave rise to the first true urban working class in Izaland’s history—a population both indispensable to industrial progress and increasingly restless under rigid social hierarchies.

Philosophy, sciences and discoveries

Philosophical movements also flourished in this era. Thinkers such as Akkawai Mīnhai, one of the earliest female philosophers in Izaki history, questioned the moral legitimacy of hereditary privilege and wrote extensively on the concept of shinkon (心根, “the root of conscience”), which would later influence liberal reformers. In science, Sāryu Homitoshi pioneered mathematical methods for structural engineering, while the physician Masan Ikkopiri developed a rudimentary vaccine against the haimun fever, a disease that had plagued the mining communities of northern Izaland.

Despite such advances, industrialization deepened social inequality. By the early 19th century, the gap between the newly wealthy industrialists and the impoverished laborers had become a source of mounting unrest. The old Nakai monarchy, now largely ceremonial, proved incapable of mediating between the demands of progress and the grievances of the populace. Strikes, food riots, and the rise of secret republican societies signaled the erosion of royal authority.

These decades of tension would culminate in the revolutionary movements that finally swept away the Nakai dynasty, paving the way for the parliamentary republic that would define modern Izaland. Yet, even amid upheaval, the proto-industrial era remained a period of profound creativity—a crucible in which the foundations of the contemporary Izaki state, economy, and identity were forged.

The 19th century, the first attempts of a Republic, and a still divided country

The Emergence of the Working Class and the Fall of the Nakai Dynasty

With the advent of modern industrialization in the 19th century, Izaland underwent significant social and economic changes. The rise of an urban working class led to widespread social problems, which the Nakai monarchy proved unable to adequately address. The increasing economic disparity and lack of reforms fueled dissatisfaction, creating fertile ground for revolutionary ideologies. Democratic and republican ideals spread rapidly across the country, inspired by Kojo’s transformation into a unitary republic (1834) and Bai’s transition into a constitutional monarchy. Similarly, the events in Belphenia added momentum to calls for change.

This growing unrest culminated in the Panaireki Revolution (若浦革命) of 1877, which overthrew the Nakai dynasty and marked the end of monarchic rule. The establishment of the Izaki Republic followed shortly thereafter, signaling the beginning of a new political era.

The Kubori Secession and Rising Tensions

Despite the revolutionary success, the newborn Izaki Republic quickly fractured. Kubori, citing cultural and political differences, declared independence as the Republic of Kubori, led by Kovira Shinpei (涑田進平), its first president. Leaders on the island accused the mainland of being "brainwashed" by Western Ulethan ideals, viewing the republican government as weak and overly influenced by foreign political philosophies. Kubori retained its connection to traditional Izaki culture while fostering a progressive political climate that increasingly leaned toward socialist ideals.

The mainland Izaki Republic, on the other hand, struggled to maintain stability. A lack of cohesive governance left the republic vulnerable to both internal dissent and external threats. This fragility created the conditions for more authoritarian tendencies to emerge.

Ðenkuku’s Autonomy and the Mainland’s Decline

During this period of upheaval, the northern territory of Ðenkuku (now part of Wendmark-Ðenkuku) negotiated greater autonomy. The already strained relationship between Ðenkuku and the mainland deteriorated further as Izaland focused on its disputes with Kubori. Eventually, Ðenkuku formally separated from Izaland in 1902, joining a union with Wendmark.

Meanwhile, on the mainland, political instability persisted. President Markus Razuyaki, partly of Kalmish descent, capitalized on the fragmentation and declared himself, on October 3, 1902, "order protector" (秩序之維持者), effectively ending the republic and establishing an autocratic regime in the span of a few months. Markus de facto had just started his own Razuyaki dinasty, and in 1916 Izaku officially became the Kingdom of Izaland in the Western media.

Samitomi Koaryu and Kubori’s Prosperity

Under the leadership of Samitomi Koaryu (宗庭哲樹), the third president of Kubori flourished both politically and economically. Samitomi's administration championed progressive policies, including labor rights, universal education, and infrastructure development, which bolstered Kubori’s identity as a forward-thinking and culturally vibrant nation. Kubori’s governance contrasted sharply with the mainland flawed presidency's autocratic rule, further deepening the ideological divide between the two states.

Samitomi’s leadership made him a revered figure in Kubori and a symbol of resistance against the mainland’s authoritarianism. However, his growing influence also made him a target of suspicion and hostility from the mainland government, which saw Kubori’s progress as a threat to its regional dominance.

The Assassination of Samitomi Koaryu and Civil Unrest

On the morning of March 15, 1925, tragedy struck Kubori with the sudden death of Samitomi Koaryu under mysterious circumstances. While the official narrative attributed his death to illness, rumors of foul play quickly spread. Many in Kubori suspected that the mainland Izaki monarchy had orchestrated an assassination to weaken the island's political stability and pave the way for annexation.

The loss of Koaryu left a power vacuum in Kubori, leading to infighting among political factions. Socialist, democratic, and conservative groups vied for control, plunging the island into a period of civil unrest. This instability provided the mainland with the pretext it needed to intervene, framing its actions as an effort to restore order and unity.

The Annexation of Kubori

By June 1925, the Izaki Kingdom launched a military campaign to seize control of Kubori. Exploiting the island's weakened state and internal divisions, the mainland successfully annexed Kubori. Although the monarchy (Izaki) claimed the annexation was a unifying act, many saw it as an aggressive move to suppress dissent and consolidate power.

The annexation marked the end of Kubori’s brief independence and its experiment with progressive governance. However, the memory of Samitomi Koaryu and his vision for a more equitable society remained a potent symbol of resistance for many Kuborians.

A Legacy of Division

The events surrounding Kubori’s annexation highlighted the stark ideological and cultural contrasts between the mainland and the island. While the mainland monarchy prioritized consolidation and control, Kubori’s short-lived independence represented a path not taken—a vision of a more inclusive and progressive Izaland. These divisions would leave a lasting impact on the country’s history, shaping its political landscape for generations to come.

Later 20th century

Until the mid 40s, Izaland remained a totalitarian state, when King Cherusoi III (彦愈三世, cherusoi sanse), nephew of Markus Rayuzaki, began a series of democratic reforms, which halted briefly when a faction launched a coup and assassinated the Izaki King, igniting the the New Foundation Revolution (新建國革明, shin-kyenkuku kakumyei) that eventually brought an end to the Izaki Kingdom and the establishment of the modern republic through a popular referendum held on 23 September 195x.

Blönnish invasion

[TBA]

Geography - 地形

Main article: Geography of Izaland

Main article: Geography of Izaland

Izaland is located on the Axian Peninsula of southeastern Uletha with a land area of 307,242.72 km². The country is divided into two major areas by the Tanden Strait: Continental Izaland and Kubori Island, the latter of which comprises about 20% of the country's landmass. While the national capital of Sainðaul was founded on the continental half of the country, it has expanded and now spans across the Tanden Strait. Continental Izaland shares land borders with Belphenia and Nuen to the east; UL28h, Sãikyel, and Blönland to the north; and Pyokchin to the west. Kubori Island faces the South of Pa at the south and shares maritime boundaries with Pyokchin and Belphenia.

Izaland can be divided into five general geographic regions: the northeastern region of broad coastal plains and lakes; the east continental region of mountains and valleys; the west continental region of marshlands; the south region of high mountain ranges and narrow coastal plains of Kubori; and a southwestern region of archipelagoes and river basins. Despite the rugged terrain of Kubori Island, most of Izaland's key urban cities – including Sainðaul and Warohan – are located on the island. Other medium or smaller cities are located on the western plains of Izaland.

Mount Torahashi, located on the Aigan Range that demarcates the border between Izaland and Blönland, is the tallest mountain in Izaland at 5,187 meters. Considered a sacred place by the Izaki people, the mountain holds significance in Izaki culture and has been incorporated into Izaki folklore. Other prominent ranges include the Kajurahi Mountains, which extends across the eastern side of the country and extends to Kubori Island.

Climate

Thanks to the privileged position, and the north-south extension of the country, Izaland enjoys different climates, from the alpine to the tropical one. Most of the population lives in a humid subtropical climate area, with a distinctive distribution on the western coast of the island of Kubori, and the plains placed in the center - western part of the Ulethan side. The average temperature in the capital, Sainðaul, is around 20,5 °C, with maximum average of 30 °C and minimum average of 12 °C

The climate zone can be roughly divided into three zones: the northern area, close to the Aigan Mountain Range, including 5000 m high peaks, sees continental to alpine climate. This area sees frequent snowfall between December to early March. Moving to the area around the capital, the climate shifts to humid subtropical, with long hot summers, cool winters, and summer peak to annual precipitation. On the south-western tip of the insular part of the country, the subtropical climate has some tropical characteristics, while the south-east and the east coast has a tropical monsoon climate, with a wet season from May to October, a dry season from November to April, and consistently very warm to hot temperatures with high humidity.

Ogamoton , Sānpelui and Kotohawa islands, in the south, have a lowest temperatures which never go below 15 °C even during the winter, making them an international holiday resort, especially famous for diving and leisure sports.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Demographics

| Demographics of Izaland | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demonym | Izaki | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Izaki | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized minority languages | Aynu Itak, Konbaki, Eituus | ||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnicities | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Literacy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Life expectancy | |||||||||||||||||||||

Izaland boasts a population of over 117 million inhabitants. This substantial number places Izaland among the most densely populated nations in the region, with approximately 385 people per square kilometer. Remarkably, despite its density, certain areas, such as the vast inner regions of Kubori Island and the northeastern continental area, remain relatively untouched by intensive urban development.

The vast majority, 92.1%, of the population identifies as members of the Izaki ethnicity, forming the cultural backbone of the nation. The remaining 7.9% comprises a vibrant community of immigrants, hailing primarily from neighboring Axian countries like Kyōwa, and Northern Archanta. Additionally, expats from other Ulethan nations such as Belphenia, Kojo, Pyokchin and Saikyel have also contributed to Izaland's recent cultural diversity.

Urbanization has played a significant role in shaping Izaland's demographic landscape. A considerable 83.2% of the population resides in urban centers, drawn to major economic hubs that have thrived since the early days of industrialization. This trend continues to attract young individuals from rural areas seeking opportunities in these bustling metropolises.

Growth rate and fertility

The demographic landscape of Izaland is undergoing significant changes, characterized by an aging population and increased life expectancy due to advancements in medical care. Additionally, the nation has experienced a rise in immigration. Despite the population boom that followed the Great War, the country is facing a challenge with extremely low population growth, primarily due to a low birth rate. In 2009, Izaland recorded the lowest absolute population growth since 1900.

The Izaki population experienced significant growth in the 1960s, with peak growth rates ranging from 5.5% to 11.3% per year. However, over time, this growth rate gradually declined, reaching a near-static -0.09% in 2009. The nation faced challenges due to low fertility rates and an increasingly aging population, resulting in an imbalance.

These demographic developments have far-reaching implications for health care and social security policies. As the Izaki population continues to age, the proportion of people of working age in relation to the overall population is declining. This trend poses challenges to the current system of old-age pensions, as fewer people contribute to the system while there are more recipients. Moreover, the anticipated increase in health care costs further compounds the situation.

In response to these challenges, the National Statistics Office of Izaland has highlighted the need for reform in health care and social security systems.

To address this demographic challenge, the Government, particularly the Araigaji cabinet, initiated measures to support young families by improving their welfare conditions. Additionally, efforts were made to attract quality migration from other developing countries. These policies started yielding results from the mid-2010s, leading to a timid but noteworthy increase in the population growth rate to 0.82% in recent years.

Policy reforms are being implemented to address these issues, aiming to incentivize more people to join the labor market and create a greater awareness of health care spending. The focus on welfare and strategic migration has proven essential in reshaping Izaland's demographic landscape, allowing the nation to sustain a more balanced and dynamic population growth trend in the face of demographic changes.

Family composition

Izaland underwent significant demographic and economic transformations before and after the Great War, leaving a profound impact on Izaki families. During this period, families became smaller, with the average number of persons per family dropping from 4.1 in 1940 to 2.5 by 1968. While family composition remained relatively stable over the quarter-century, there were notable percentages in various family types. In 1975, 24.4% of families consisted of a man and a woman, 61.9% of a couple with children, 11.8% of a woman with offspring, and 1.9% of a man with offspring.

One significant change was observed in the number of children per family, which declined from an average of 3.43 in 1950 to 2.9 in the mid-1980s. Large families became rare, as only 3% of families had four or more children. On the other hand, 47% of families had one child, 44% had two children, and 6% had three children.

The impact of these demographic shifts was evident in the number of Izaki individuals under the age of 18, which decreased from 39 million in 1960 to 17.3 million in 1980. These changes in family size and composition have contributed to shaping the social fabric of Izaland and have implications for future demographic trends and policies.

Surnames in Izaland

Surnames in Izaland reflect the country’s richly layered cultural and linguistic heritage. While most Izaki family names derive from native traditions, the diversity of regional influences—ranging from Bai, Kalmish, Eelantian (Finno-Ugric), to Ainu—has produced a unique and complex onomastic landscape. These surnames function not only as identifiers but also as markers of ancestry, profession, and geography.

Structure and Usage

The majority of Izaki surnames are composed of two Bai-derived characters, written in Askaoza (𖬠𖬒𖬧𖬠𖬜), the local logographic script. These names often relate to natural elements, occupations, or abstract virtues. The typical phonological pattern favors CV (consonant-vowel) structure, but Izaki also permits word-final consonants such as -n, -r, -l, -s, -h, providing moderate flexibility. Triple consonant clusters, however, are avoided.

Lineage Names (譜名)

In addition to their main surnames, around one-sixth of the population also bears a lineage name, or 譜名 (pumei), which consists of a single character inserted between the given name and surname. This tradition has roots in the classical naming systems of the southern Paichew/Bai kingdoms and was historically a sign of clan or ancestral affiliation. Common lineage characters include 金 (Kin), 百 (Pyaku), 李 (Rī), 張 (Chaan), and 宮 (Kūn).. Common examples include:

- Kin (金) – gold

- Rī (李) – plum

- Pyaku (百) – hundred

- Zhin (陣) – battle line

- Chaan (張) – to stretch

- Fuku (福) – good fortune

- Kūn (宮) – palace

Regional Origins and Influences

Native Surnames

Native surnames dominate throughout the country and form the foundation of Izaki onomastics. These names are typically composed of two byakuzhi characters and reflect traditional values, professions, or geographic features. Examples include:

- Hansai (飯斎) – “Meal Ceremony”

- Samosāri (山川) – “Mountain River”

- Ōdasayo (大木) – “Great Tree”

- Kanlisoma (船造) – “Ship Maker”

- Tsawano (森見) – “Forest View”

- Raibu (田中) – “Ricefield Center”

These names are distributed evenly throughout the country and remain the most commonly registered surnames in census data.

Kalmish-derived Surnames

Kalmish (Germanic) surnames are prevalent in northwestern Izaland, particularly in prefectures such as Anbira, Nikorenatsuki, Yenkaido, Usmashaki, and Riyatoma. Some of these surnames originated in the High German-speaking regions of Uletha and were gradually adapted to Izaki phonology during medieval and colonial periods.

Examples:

- Beruman (from Bergmann) – “mountain man”

- Sunaidār (from Schneider) – “tailor”

- Furidiris (from Friedrichs) – personal name adaptation

- Revanta (from Reinhardt) – “brave advisor”

- Tsopel (from Zobel) – “sable fur trader”

These names typically underwent consonantal softening or vowel regularization, and were integrated into local naming systems, sometimes blending with native suffixes. They are usually written in askaoza alone.

Eelantian-derived Surnames

In the central and eastern parts of Izaland—particularly in Doonpuku, Sahasamo, and Yuttsamo—surnames of Eelantian (Finno-Ugric) origin form a distinctive linguistic substratum. These names often derive from nature, especially related to water, hunting, and forest life. Their structure leans toward polysyllabic forms, often ending in -la, -ri, -nen, or -ta, and are slightly adapted to conform to Izaki phonology.

Examples:

- Yarvinen (from Järvinen) – “lake dweller”

- Koskī (from Koski) – “rapids”

- Metasara (from Metsälä) – “forest place”

- Lautana (from Lauttaniemi) – “ferry cape”

- Vakkunen (from Vakkunen) – possibly “small vessel maker”

These names may be seen in family registries alongside native given names, illustrating Izaland’s ethnic and cultural integration over the centuries.

Ainu-derived Surnames

Ainu-derived surnames are most commonly found in Yenkaido Prefecture and other areas with a historical Ainu presence. These names, often symbolic of animals, spirits, and natural forces, preserve linguistic elements from pre-Izaki times and are among the oldest layers of surnames in the country.

Examples:

- Kamur, Kamwi, Kamu (from Kamuy) – “deity, spirit”

- Setan, Seta, Sedan (from Seta) – “dog”

- Relar, Reira (from Rera) – “wind”

- Epan, Ippai (from Ipan) – “bow”

- Punanak, Punanai (from Ponanak) – “to bloom” or “flowering place”

Though often adapted phonetically into the Izaki language, these surnames maintain distinctive syllabic structures and are culturally important as part of Izaland's indigenous heritage.

List of common Izaki surnames

In Izaland, the majority of surnames are crafted from two Bai characters, often imbued with meanings tied to geography or professions. With a repertoire of over 182,000 family names, Izaland boasts a diverse array of surnames that are widely dispersed across the nation. Among them, the most prevalent ones, such as Hansai and Samosāri, name about one million individuals each.

Notably, around 1/6 of the population also possesses a middle family name, traditionally formed from a single character, a historical vestige of connections with the southern Kingdoms of Bai. Among these middle names, some of the most common ones include 金 (Kin), 李 (Rī), 百 (Pyaku), 陣 (Zhin), 張 (Chō), 福 (Fuku), 宮 (Kūn), among others. This rich tapestry of surnames reflects the intricate cultural heritage and historical influences that have shaped Izaki society.

| Rank | Name | Askaoza | Romanization | Estimated number (2020) | Occupation rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 飯斎 | 𖬨ᐢ𖬖ᐟ𖭐 | Hansai | 1,129,990 | 0.96 |

| 2 | 山川 | 𖬖𖬊ᐤ𖬖։𖬬𖭐 | Samosāri | 1,092,229 | 0.93 |

| 3 | 船造 | 𖬭ᐢ𖬈𖭐𖬖ᐤ𖬊 | Kanlisoma | 928,002 | 0.79 |

| 4 | 田中 | 𖬬𖬒𖭐𖬡𖬰𐐢 | Raibu | 919,220 | 0.78 |

| 5 | 大木 | 𖬒ᐤ։𖬣𖬰𖬖ꓩ𖬮 | Ōdasayo | 857,229 | 0.73 |

| 6 | 森見 | 𖬑𐩬𖬒𖭑ᐤ | Tsawano | 843,002 | 0.72 |

| 7 | 鹿田 | 𖬣ᐤフ𖬣ᐢ𖬨ᥫ𖬬 | Tottanheira | 728,229 | 0.62 |

| 8 | 神仕 | 𖬨𖭑ᦴ𖬬𖭑 | Hanuirana | 701,992 | 0.59 |

| 9 | 賈網 | 𖭑𐐢𖬣𖬖𖬰ᐤ𖭐 | Nutazoi | 629,220 | 0.53 |

| 10 | 西村 | 𖭑𖭐𖬥𖬰𖭐𖭑𖬣 | Nijinata | 402,339 | 0.34 |

| 11 | 島人 | 𖬨𖬊𖬣ᐤ | Hamato | 381,002 | 0.32 |

| 12 | 長崎 | 𖬬ɭ𖬭𖬰ɭ𐐢ᐡ | Regeul | 352,997 | 0.30 |

| 13 | 鍛冶 | 𖬖ᐟ𖭐フ𖬭ɭᒢ | Saikkes | 312,002 | 0.29 |

| 14 | 平 | 𖬊フ𖬭ᥫ | Makkei | 282,002 | tbd |

Inheritance and Surname Law

Traditionally, children inherit their father's surname, a practice that remains dominant across the country. However, following the enactment of the Surname Reform Act 改革姓氏法 (kaikyokuseishihō) in 2012, parents may now legally choose which surname—maternal or paternal—is passed down to their children, provided both parents agree at the time of registration.

Women traditionally retain their surnames after marriage. Nevertheless, since the Marriage Naming Flexibility Law 婚姻氏選擇權法 (honninshisentakkwonhō), they may optionally adopt their husband's surname for social or administrative reasons. Both versions may appear in official registries if explicitly requested.

In some cases—particularly among families reclaiming suppressed or altered heritage surnames—the Ancestral Surname Restoration Law 祖姓回復法 (soseihwifukuhō) (2021) allows individuals to formally restore ancestral surnames that were modified during prior assimilation periods, particularly those of Aynu, Eelantian, or Kalmish origin. This law has seen increased use in recent years among younger generations seeking to reconnect with local or minority cultural identities.

Ethnicity

It is difficult to trace a genetic profile of the Izanish race, as since the dawn of time there has been a profound mixture of different ethnic groups, both Uletian and Arcanthic. Physiognomically, Izanish people's face appears to be of an oriental type, with dark hair, black almond-shaped eyes and a slightly pronounced nose. However, there is no lack of genotypes belonging to more Western races, such as lighter colored eyes (ocher, olive green and, very rarely, blue) and hair tending to brown.

Tracing a precise genetic profile of the Izaniki ethnicity poses a challenge, given the deep historical amalgamation of diverse ethnic groups, both from Uletian and Archantan origins. Physiognomically, Izaniki individuals typically exhibit facial features reminiscent of oriental or North-Archantan descent, characterized by dark hair, black almond-shaped eyes, and a slightly pronounced nose.

Nevertheless, the genetic diversity extends to include genotypes associated with Western races, such as lighter-colored eyes in shades of ocher, olive green, and, on rare occasions, blue, along with hair shades tending towards brown. This intriguing blend is particularly observable in the northern regions, where frequent interactions with Kalmish populations have taken place in recent history.

Despite these influences, Izaland's geographical isolation, framed by surrounding mountains and the sea, has largely contributed to maintaining relatively uniform somatic tracts throughout the nation's history.

Urban planning

A characteristic of the territorial development of Izaki urban centers lies in the fact that, compared to other nations, there are few small isolated villages, while the number of large and medium-sized cities is greater. This is due not only to a greater ease in the distribution of goods, but also to the ancient philosophy of "jiyenchohwashisān" (自然調和思想), or "thought of harmony with nature", drawn up from the 5th century BC by the Taemasa dynasty.

This method of land planning was based on both scientific and astrological criteria, and the positioning of towns and villages was well defined. As the Taemasa dynasty aggregated, through conquests, new territories that had independently developed their regional urban planning, it came, in certain cases, to relocate entire villages, if they did not respect the precepts of the "jiyenchohwashisān".

Although urban planning is still based on modern criteria, the ministry of the environment keeps a careful eye in order to avoid land consumption in the territory.

Education

Education in Izaland is a cornerstone of national development, recognized for its high literacy rate (nearly 100%) and emphasis on multilingualism. The education system blends traditional values with cutting-edge innovation, producing a workforce adept at navigating both local and global challenges. With a minimum of 14 years of compulsory education and globally ranked universities, Izaland fosters academic excellence and cultural exchange, serving as a bridge between the Bai-sphere and Kalmish/Western Ulethan cultures.

Structure and Governance

The education system in Izaland is centrally managed by the Ministry of Education and Research (教育研究部, Kyōiku-Kenkyunbu). This ministry oversees curriculum standards, teacher training, and the allocation of funds to public institutions. Despite this centralized structure, private institutions also play a significant role, especially in higher education and specialized fields.

Education Stages

Education in Izaland is divided into several stages:

- Primary Education (初等敎育): Lasting 5 years (ages 5–11), primary school focuses on foundational literacy, numeracy, and an introduction to Izaki culture and values. Students begin learning Ingerish as a second language in the 2nd grade.

- Secondary Education (中等敎育): This 4-year stage (ages 11–15) deepens subject knowledge and introduces critical thinking. Middle school students also begin studying a second foreign language, often choosing between Kalmish, Nihonese, or Pyeokchinese.

- Tertiary Education (高等敎育): Lasting 4 years (ages 15–19), tertiary education prepares students for university or vocational careers. This stage is highly competitive, with national examinations determining university placements.

- University Education (大學敎育): Undergraduate programs typically last 3 years (ages 19–21). Postgraduate studies span 2–3 years, with research-intensive fields like technology, medicine, and engineering being particularly popular.

Compulsory education spans the first 14 years (primary through tertiary), ensuring every citizen receives a robust foundational education.

Languages of teaching

The primary language of instruction is Izaki, though regional languages such as Aynu-itak are incorporated in areas like Yenkaido and Doonpuku. Ingerish, introduced in the 2nd grade of primary school, becomes increasingly significant in middle school, where some core subjects are taught in Ingerish to prepare students for global careers.

By secondary school, students are required to learn a second foreign language, with Kalmish, Nihonese, and Pyeokchinese being the most common choices. This multilingual approach reflects Izaland’s role as a cultural and economic mediator in Eastern Uletha.

Higher Education

Izaland is home to a network of prestigious universities, including the Sainðaul National University, Warohan University, and Illashiya Normal School, collectively known as the “Nankwan Daikaku” (難関大學, "Hard-to-Enter Universities"). These institutions are renowned for their rigorous entrance exams and high academic standards.

Popular research fields include technology, medicine, engineering, mathematics, astronomy, and nutrition, with a growing focus on sustainability and green innovation. Izaki universities also emphasize the arts and history, preserving the country’s rich cultural heritage while fostering innovation.

Private vs. Public Education

Izaland’s education system is predominantly public, but private schools and universities cater to families seeking specialized programs or smaller class sizes. Public schools are funded by the government and maintain high standards nationwide, ensuring equitable access to education.

Private institutions, though fewer in number, excel in niche areas such as arts, international relations, and advanced scientific research. Tuition fees in private schools are higher, but scholarships are available to promote inclusivity.

International Influence and Exchange

Izaland’s education system reflects its role as a bridge between the Bai-sphere and Western Uletha. The country participates in international student exchange programs, such as the EUOIA Exchange Program, which allows students to study in other member nations without tuition fees. A similar program has been established with select North Archantan nations since 2004.

To attract global talent, many Izaki universities offer degree programs in Ingerish or Kalmish, ensuring accessibility for foreign students. This approach has strengthened academic and cultural ties with partner nations while enhancing Izaland’s reputation as an education hub.

Recent Developments

While Izaland is a pioneer in adopting digital technologies for education, concerns over students’ dependence on technology have led to a revival of traditional teaching methods. Schools are reintroducing hands-on workshops, outdoor activities, and discussion-based learning to balance technological innovation with interpersonal and critical-thinking skills.

Additionally, efforts to reduce academic pressure and foster student well-being are being implemented. These include reduced homework loads, flexible class schedules, and increased emphasis on creativity and collaboration.

Government - 政府

Main article: Government of Izaland

Main article: Government of Izaland

Izaland is a parliamentary republic, and the governance of Izaland is divided into three branches: executive, judicial, and legislative. The President is the country's head of state. Executive power is vested in the Council of Ministers – a cabinet led by the prime minister. The President appoints the prime minister, and upon the advice and consent of the prime minister, appoints the other ministers in the Council. The Council of Ministers must obtain the confidence of the Daiwiwinkwi and is collectively responsible for all government policies and the day-to-day administration of state affairs.

The main legislative body is the Izaki National Assembly (Kukkaiwishidān, 國會議事堂), which comprises the Daiwiwinkwi 代議員會 (upper house) and the Gwannowin 元老院 (lower house). The Daiwiwinkwi has 530 members while the Gwannowin has 208 members; the members in both houses are directly elected through general elections held every five years. Both houses of the Kukkaiwishidān are responsible for enacting the laws governing the state. The president holds limited discretionary powers of oversight over the government, and the president's veto powers are further subject to parliamentary overruling.

The Supreme Court (最高裁判院, Tsaikosaipannwin) is the country's highest judicial organ. It is composed of judges appointed by the President of the Republic under the recommendation of the National Council of the Judiciary for an indefinite period, and also by the Constitutional Court (憲法裁判院, Kenpōsaipannwin), which is composed of 28 judges chosen by the Chamber of Deputies for a six-year term.

The President of the Republic (大統領, "Daitsōnlyān") is directly elected by popular vote for a renewable five-year term. Nominally, the president oversees the country's foreign policy and national defense as the commander-in-chief of the Izaki Self-Defense Forces. The president also chairs the High Council of the Judiciary. A presidential term may end due to voluntary resignation, death while in office, or dismissal by the National Assembly for crimes of high treason, as it has happened with the Tsawano Impeachment case of 1983. If a presidential vacancy should occur, a successor must be elected within sixty days, during which presidential duties are performed by the prime minister or other senior cabinet members in the order of priority as determined by law.

Flag

| Color scheme | Dark Gray Blue | Red | White |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMYK | 0/79/84/27 |

0/29/78/0 |

90/67/0/34

|

The Izaland flag consists of a blue background, inside which there are two concentric circles, a central red one, surrounded by a white ring. Blue, the symbolic color of Izaland, represents at the same time the color of the sea, and of the numerous streams and lakes that cover the surface of the nation. The red circle indicates the rising of the sun in the east, a direction that has always been of great importance for Izaland, as to the east there is the open sea, and therefore all the trade routes. The white surrounding the red sun indicates the light of the midday sun which, thanks to its heat, allows agricultural activities to flourish. Similarly, the white color is an element with a strong symbolism as an element of purity, according to the Izaki philosophy.

Administrative Divisions and cities

Main article: Administrative divisions of Izaland

Main article: Administrative divisions of Izaland

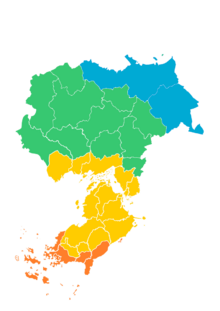

Izaland is divided into 27 subnational entitles, including 24 prefectures (縣, ken), the Capital Special Administration District (首都特別自治区, Shuto tukubyeschitsiku), the special city of Warohan (深湾特別市, Warohan tukubyesshi) and the special self-governing prefecture of Yenkaido (遠海土, Yenkaido). Each has a semi-autonomous local government with executive and legislative bodies, the members of whom are elected through local elections. Duties of local governments include social services, education, urban planning, public construction, water management, environmental protection, transport and public safety. The prefectures are further divided into cities (市, -shi), towns (町, -chō), and villages (村, -son).

Economy - 経濟

Main article: Economy of Izaland

Main article: Economy of Izaland

Izaland has one of the world's largest economies in the world and stands a regional leader in science and technology. The quick industrialization and rapid growth of the country following the Great War have been called the "Miracle of the Tandan Strait". Izaland's high quality of education has also significantly contributed to the country's economic prosperity, with a literacy rate of nearly 100%. Izaland has a low unemployment rate of around 2.16% and maintains a low poverty rate, although some economic and developmental disparities persist between country's rural and urban regions.

Being rich in natural resources, the country is also a major exporter of natural and agricultural resources, and its economy is traditionally focused on the manufacturing and electronics industry. Izaland is renowned for its shipbuilding capabilities, as well as the production of railway locomotives and vehicles. Izaland is also a key manufacturer of semiconductors, radars, engines and screen panels, and exports furniture crafted from kamawi tree wood. Recently, the Izaki economy has placed greater focus on the tertiary sector, including communications, services, finance, and tourism. As an export-oriented mixed economy, it is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises rather than large business groups. This is partly due to the government's intervention of the 90s that saw greater regulation of the ðaipwas (財閥), which previously held great influence in the country's economic and state affairs.

Transport and infrastructure

See also: Infrastructure in Izaland

See also: Infrastructure in Izaland

Izaland boasts a comprehensive and well-developed infrastructure to support its high demand for transportation. The country's railway network is extensive, comprising 2,263.36 km of high-speed rail and 16,418.29 km of standard-speed rail, all operating on standard gauge tracks (1,435 mm) with some sections also utilizing narrow gauge. Known for its punctuality and reliability, the rail system offers frequent and efficient commuter and long distance lines operated by Izarail, in conjunction with local subway networks and private railways.

For road transportation, Izaland features an intricate network of highways, including the main E1 (Keishin) highway that links the capital to Warohan, passing through major cities along the western coast of Kubori Island. This segment serves as the busiest route, as nearly 60% of the country's population resides along its path. Due to the country's geological and geographical characteristics, highways often incorporate tunnels and bridges, leading to high toll charges.

The country's air transportation is centered around the prominent Sainðaul Asunahama International Airport, a major hub for Izaland Airlines and Uletha Eastern Airways. With over 400 islands, water transportation plays a vital role, connecting the mainland to offshore islands through ferry services and bridges. The national transportation transit system IZWay facilitates sea travel with a rechargeable smart card payment system.

In terms of communication, Izaland boasts one of the most advanced networks globally. 97 million people used mobile phones to access the internet in 2019, representing approximately 86% of individual internet users. Nearly 98.3 million people (84.0% of the population) utilize the internet, enjoying the world's fastest average internet connection speeds, especially in major cities with Gigabit class connections. Furthermore, the availability of 5G mobile lines covers all prefecture capitals, with a reach of 13.5% across the country as of 2022.

Culture

Visual Arts

The visual arts of Izaland possess deep historical roots and showcase a fascinating blend of influences. The heartland of artistic development, particularly during the formative Illashun Era, lies in the southern regions historically connected to mainland Ulethan cultures. Here, themes drawn from the natural world became central motifs. Concurrently, in the northern territories, early inhabitants left behind distinct cavern and rock wall paintings, typically depicting vivid scenes of hunting and fishing life from a time before centralized states held sway.

A definitive direction for Izaki art emerged significantly under the influence of the powerful Huaxian Kingdoms, notably the Soh and Peichew states. This contact introduced sophisticated aesthetics, techniques, and philosophies that shaped many art forms. Alongside these developments, Dharmapala art, particularly its rich tradition of sculpture, became a profoundly important element within the Izaki visual landscape. Later, around the 14th century, Ekelian Christicism introduced new artistic currents, notably the technique of mosaic, which was integrated in remarkable ways, sometimes even appearing in Dharmapala contexts – exemplified by the intricate golden mosaic ceiling decorations of the famous Rinkān-ji Temple in Illashiya, now recognized as a World Cultural Heritage site.

Painting and Calligraphy

Traditional Izaki painting is heavily indebted to the ink wash techniques originating from Huaxian influence, perfected by masters like Kaiyos Ryenshu (海越 連衆), whose 'Mists over Mount Hakko' remains a celebrated work. Initially, subjects focused predominantly on landscapes, capturing Izaland's dramatic mountains and coastlines, and detailed studies of animals and plants. Calligraphy, considered a sister art to painting, also developed significantly under Huaxian influence, valued for both its aesthetic beauty and its connection to literature and administration. Over time, however, increasing contact and influence from Kalmish cultures broadened the thematic scope, leading to a greater prevalence of human figures and portraiture in painting. Hanuist traditions also contributed uniquely, often inspiring depictions of personified natural elements within paintings.

The arrival of Ekelianism further diversified the field, introducing oil painting techniques and the aforementioned art of mosaic, often employing the color gold for its symbolic, ethereal connotations in religious works.

While Ekelian artistic styles associated with the state-endorsed religion gained official prominence after 1592, this dominance was not absolute or constant. Periods of conservative reaction within the ruling class, sometimes driven by fears of excessive foreign influence weakening Izaland's sovereignty, occasionally led to renewed royal or noble patronage for traditional Huaxian-inspired or indigenous Hanuist aesthetics. This created a dynamic artistic tension and patronage landscape over the centuries.

This confluence of strong, persistent traditions fostered both genre specialization and rich artistic experimentation. Ink wash often remained the preferred medium for classical landscapes, nature themes, and calligraphy, while oil painting and Kalmish-influenced realism frequently became the choice for formal portraiture, detailed historical narratives, and Ekelian religious commissions. Simultaneously, many Izaki artists became adept at creating innovative hybrid styles, skillfully blending techniques, perspectives, and sensibilities drawn from these diverse sources.

From around the 18th century onwards, reflecting Izaland's position as a continental nation engaging with wider trends, Izaki painting increasingly interacted with broader Ulethan artistic currents (analogous to RW European Neoclassicism, Romanticism, Realism, etc.), adapting them to local tastes, philosophies, and themes. A pivotal figure bridging traditional sensibilities and these newer influences in the early 19th century was the painter Mihaki Junnaroi. Active during a period of heightened national consciousness, Junnaroi became celebrated for his large-scale historical paintings. These works often employed Western techniques of composition, perspective, and realism to depict pivotal moments from Izaki history and mythology with dramatic flair, resonating with a growing sense of national identity.

Subsequent generations continued to navigate the influx of external ideas, grappling with movements analogous to Realism, Impressionism, and various forms of Modernism. This ongoing dialogue between internal traditions and external influences led to further diversification and the emergence of distinctly modern Izaki painting styles in the contemporary era, representing a unique synthesis of its complex artistic heritage.

Sculpture

Sculpture in Izaland prominently features works related to its major religious traditions, primarily utilizing bronze and wood. Antarajnana Dharmapala statues, such as representations of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, generally resemble styles found in northern Huaxia and other countries in the Axian peninsula, notably lacking the cranial protuberance (ushnisha) sometimes seen in other Dharmapala traditions further south in Archanta. A famous example is the original set of 18 Bodhisattva statues (of which 13 survive) at the Daihō-ji temple in Warohan (also a World Heritage Site), exemplified by the serene primary bronze Buddha sculpted by Master Eshin (恵心).

Hanuism's sculptural output, in contrast, tends to be less focused on anthropomorphic figures and more on functional or architectural elements; examples include intricately carved ceremonial instruments or decorative portions integrated into the structure of Sumatai shrines.

Ekelian Christicism spurred another wave of sculptural activity. Initially, many statues of saints and other church elements were directly imported. Subsequently, a local tradition flourished, especially in northern Izaland where artists likely benefited from proximity and exchange with artisans in the neighboring Kalmish kingdoms, mastering the creation of Ekelian religious statuary. Artists like Helga Brandt (known as Helga Branti in Izaki) became particularly known for expressive wooden sculptures of Ekelian saints; her detailed sculpture depicting Simon and Peter as fishermen is considered a masterpiece within Sannupuri Cathedral.

Religion

Izaland's location as a historical crossroads between Northern, Western, and South-Eastern Uletha (and thus Archanta) has fostered a diverse religious landscape shaped by centuries of cultural exchange. While freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed, recent decades have seen a significant increase in secularism and agnosticism, particularly among the younger population. The main religious traditions historically influencing Izaland include indigenous beliefs, Dharmapala, and Christicism.

Indigenous Traditions and Hanuism

Ancient religious practices existed in Izaland, stemming from both Northern (Alvedian) and Southern influences. While the Northern cults have largely dissolved, elements persist within the folklore of Izaland's northern regions. In contrast, Hanuism (神信 shinzhin), believed to originate from ancient Southern cults, remains a significant cultural force.

Described as Izaland's unique indigenous religion (although some of its influence also spread to the near Ugawa and Miuro), its traditions are deeply interwoven into the fabric of everyday life and culture across the nation. Hanuism exhibits strong syncretic tendencies, particularly with Dharmapala, often making distinct separation difficult in practice for many adherents.

Central to Hanuist practice is the shrine, known in the Izaki language as a Sumatai. These sacred sites are characteristically established in locations possessing significant natural beauty or power, often featuring prominent trees, rocks, water sources, or groves, reflecting a profound reverence for the natural world and the spirits or energies believed to reside within it.

Typical rites

Hanuism places strong emphasis on ritual performance and communal participation. Prescribed rites and intricate ritual dances are core components of worship and community events, serving functions ranging from purification and seeking blessings to marking life passages and seasonal changes.

Some of the more intense or significant Hanuist rituals involve practitioners, potentially specialists or devotees, entering trance states. This altered state of consciousness is sometimes facilitated through the ritual consumption of seizhu (聖酒), a traditionally prepared fermented alcoholic beverage. The ceremonial use of seizhu stands in notable contrast to contemporary Izalandic society, which largely observes strict restrictions on alcohol production and consumption, highlighting the unique, protected status of this element within its sacred context. The syncretic nature of Izalandic spirituality is particularly evident in the relationship between Hanuism and Dharmapala, where practices, deities, and beliefs often intertwine.

Dharmapala

Dharmapala (拖吩羅, dapara) Introduced primarily through maritime trade with the Huaxian Empires starting around the 3rd century CE and influenced by developments in the UL-30c region (modern Ugawa and Taira), Dharmapala established a strong presence in Izaland over the centuries. Izalandic practice eventually evolved distinctly from mainland orthodoxy, culminating in the tradition known today as Antarajnana (安多礼那那, antaranana). This school remains a significant element of Izaland's cultural and spiritual landscape, though often closely intertwined with Hanuist practices.