Kojo

|

Republic of Kojo  Kojo Jōbun-Myeru (Kojoshi) Capital: Pyingshum

Population: 40,000,000 (2020) Motto: Jōbun fa, Jōbun lui (By the People, for the People) Anthem: Pāng re Maltyam (March to Glory) |

Loading map... |

Kojo (/ko̞dʒo̞/) is located on the Axian peninsular in south-east Uletha. It borders the Sound of Pa in the south, Ataraxia in the west, UL31a in the north and Pyeokchin in the east. Despite a civilisatory history dating back to the Stone Age, Kojo came into being as a unified nation state only after 1668. It is a parliamentary republic whose democratic character dates back to the revolution of 1828. Although consisting of 13 regions, called iki, political power is concentrated on the national level on one side and the municipalities on the other. Kojo has a dense network of infrastructure for road, rail, water and air transport. With an HDI of 0.903 and a GPD per capita of 57,850 Int$ (PPP, 2021), it is classified as a very highly developed country. Being the only Kojoshi-speaking nation in the world, yet at the same time having been in constant exchange with its neighboring countries, it has developed a culture marked both by unique idiosyncrasies and the incorporation of foreign traits.

Kojo (/ko̞dʒo̞/) ta Uleta so akudyong bue Kottsōchi de nambu. Aku máre Taman'yumi, limbē máre Atarakkusī, kibō máre UL31a, dyong máre Dyokkun aéku kokkyōyu. Karetaki hyeto buntamshandeaki lishi kāwaryuzu, Kojo fa 1668ttari yéri assol'yora'e azaggumyeru kuemere. Demomínzudaeki umki fa 1828ttari hyeto zádang‘u párlekaidaeki jōbunmyeru ku. Iki dash gwoshu 13so gōsaei dash kóntitueyu kāwaryuzu, sēzudaeki pyuesan fa zággaisaē ko munchipalsaē aéku icchonkwaeyu. Kojo bue laidō-, chegicha-, hún'gō- ko aenkamfuhīchon so ikaldon rézo fa nambu. Kojo so HDI fa 0.903, hyoelminkacha pa HAG fa 57,850 Int$ (PPP, 2021tali) ku sokki, Kojo sum song raiyuē ébolpang zággaitsol so alfya hyuém dashkalgaelu. Ashkal so asaso, Kojoshi sum ingamu zággaitsol dash, nōtomzū halfāndaeki zággaitsol mi umkinku ongkwoéshu sokki, Kojo ta asasong yuralchēgwin’gwae ko sochizággai áyunki sum ikkontsudoen fa umkishu tyungbon sum maekkafaeme.

Geography

| |

|---|---|

| Geography of Kojo | |

| Continent | Uletha (south-eastern) |

| Region | Axian peninsular |

| Population | 40,000,000 (2020) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 267,630 km2 |

| Population density | 150 km2 |

| Major rivers | Kime, PH |

| Time zone | WUT+7:00 (no summer time) |

Overview

The western half of Kojo is characterized by relatively infertile soil and lower precipitation compared to the rest of the country. Originally, the region was covered by bush and forest. However, much of the natural vegetation was cleared in various phases of human settlement from at least the 5th century until the early 20th century. This extensive deforestation led to significant soil erosion, depleting the thin layer of natural humus and further reducing the land's agricultural utility. Today, this area is primarily used for extensive pastoral farming, with reforestation programs initiated in the late 20th century to restore the landscape. The coastal areas of this region are notable for their wide, sandy beaches and mild climate.

In contrast, the Kojolese heartland offers more fertile soil, allowing for intensive agriculture. The fertility of the land, coupled with the presence of navigable rivers, facilitated the transportation of goods even before the advent of railways. As a result, the majority of Kojo's population is concentrated in this region. The deltas of the Kime and Dagwan rivers are part of a unique cultivated landscape, where for millennia, humans have worked to exploit the fertile, irrigated lands while contending with challenges such as storm tides and the region's inaccessibility by land.

The eastern coast, particularly in the region of Cheryuman-iki, features dramatic landscapes where mountains meet the sea. This area experiences some of the highest precipitation levels in Kojo, largely due to winds that bring humid air from the southeast oceans. The region has a pronounced rainy season in early autumn and boasts diverse flora, with a variety of microclimates that support vegetation ranging from Mediterranean to temperate rainforests.

The Kojolese heartland is bordered by low mountain ranges that rise into higher mountains to the north and east. Population and arable land are concentrated along the rivers and streams, while the mountain slopes are predominantly forested, with some areas used for mountain pastures. Above the tree line, the landscape is characterized by scrublands, barren rock, and, on some mountains over 4000 m in elevation in the far north, year-round snow. Many valleys in the northern region were converted into reservoirs during the 20th century, facilitating more effective flood control for rivers flowing toward the lowlands and providing hydroelectric power.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Topography and Bathymetry

To the north and east, Kojo is bordered by mountain chains. The country's largest river originate here before flowing towards the coast in the south, making Kojo mostly congruent to the watersheds of its largest rivers. However, exceptions to this exist. Namely, in the north-east an area of around 10,000 km² in Pyeokchin drains into the Kime watershed, in the east around Lake Bōli an area of about 3,000 km² in Pyeokchin drains into the Dagwan watershed, and an area of about 2,000 km² in northern Kojo drains towards UL31a.

The Cheers (Kojolese: Chaerbu (Nain), "white wall (mountains") refer to the continental mountain chain reaching from UL27j to UL28h. They divide the East Ulethan peninsular into a northern and southern watershed, the latter of which Kojo is a part of. While this term is also frequently used to refer to just the Kojolese part of the Cheers, the different regions also have more specific names:

- PH: mid-range mountain range spanning the western half of the boundary between Kojo and UL31a.

- PH: section of the Cheers within Nainchok-iki.

- Tachaerbu ("High Cheers"): section of the Cheers within Kyoélnain-iki. Refers exclusively to the area north of the Gwaemsónain to Doikku line.

The south-eastern mountains mark the boundary to Pyeokchin reaching from Doikku to the south-eastern tip of Cheryuman-iki. They lack an historic collective name. In modern times, when referring to this mountain chain at large, one of two names is usually used. While in scientific and legal writing, the name "Kippasōlraeinnain" (mountains of the fault line of the northern Sound of Pa) is used, in everyday speech the term Dyongbu ("east wall") is preferred. Like the Cheers, they span a very large area and contain many different landscapes, hence more local names are used when referring to individual areas:

- Hangkan'nain ("Ore mountains"): northern mid and high-range mountains east of the river Bin from Doikku to the southern border of Kyoélnain-iki.

- Appodaer (Nain) (ethymology unknown): southern border of Kyoélnain-ik to Dagwan breakthrough in Īme.

- Baelyan'yénain or Wokael: Dagwan breakthrough in Īme to Daelfi. The latter is an historic term that sometimes also refers only to the area around Rō.

- Lantsanmol (from Nihonish 嵐山系, Ransankei, "Storm mountains" and -mol for massif): Coastal massif in Cheryuman-iki east of Daelfi.

The above names are mostly used to refer to mountain chains as geological features. When referring to historic regions or holiday destinations, sometimes different names are used or the names refer to slightly different areas. For example, the name of the region Kyoélnain-iki is used when referring to the mountainous north-east of Kojo in general, with no differentiation between wether the Cheers or the Hangkan'nain range is meant. When referring to the mountainous part of Chinyaku-iki along the Dagwan and Jush valleys, the name Appodaer is often used even though the area technically also encompasses parts of the Wokael range.

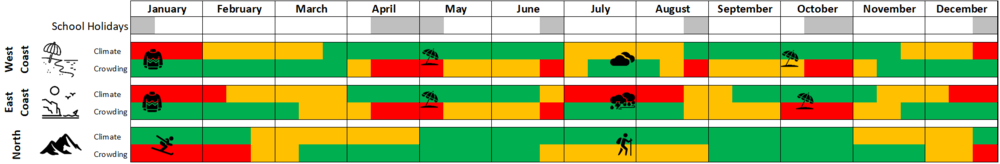

Climate

Kojo is predominantly situated within a humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa), characterized by warm, humid summers and mild winters. The majority of the country's precipitation occurs during the summer months, with July typically being the wettest month. As one moves westward, the climate gradually shifts into a cold steppe climate (BSk), a transition caused by the reduced humidity in the air masses reaching this area from the Sound of Pa to the southeast.

In Kojo's mountainous regions, temperature variations are more pronounced both throughout the year and between day and night compared to the plains. Precipitation in these areas is heavily influenced by local topography, which affects how the air currents from the Sound of Pa release their moisture. Coastal areas experience moderated temperatures due to the influence of the sea. The flat western coastline receives minimal precipitation, whereas the steep eastern coast is subject to more extreme rainfall events, reflecting the varied climatic patterns across the country.

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

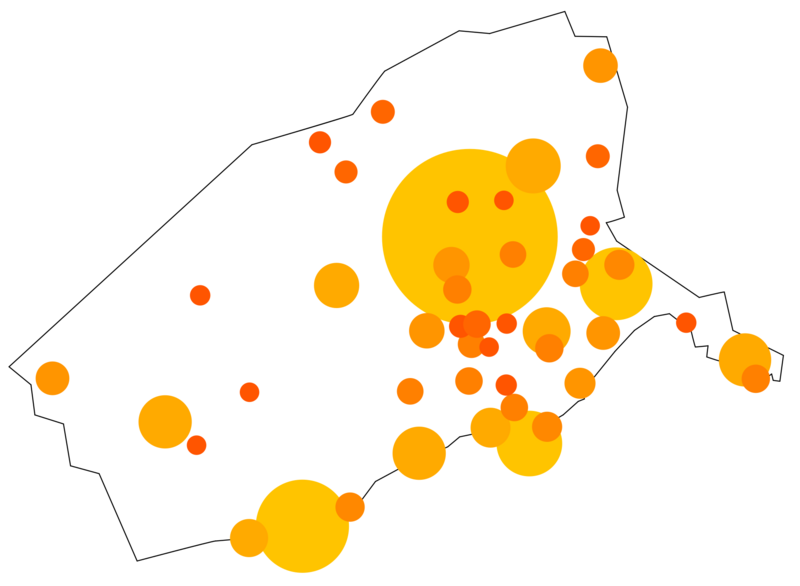

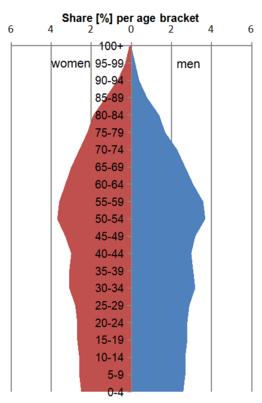

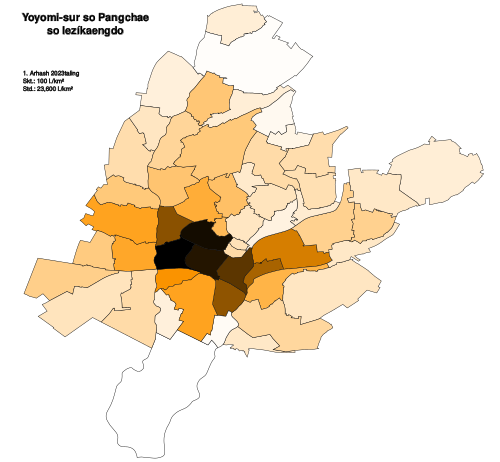

Human Geography

Kojo's population is heavily concentrated in urban areas, with nearly half of the country's residents living in cities with populations of 100,000 or more. Almost a quarter of the population resides in the capital city alone. The eastern half of Kojo is significantly more densely populated than the western half, primarily due to the presence of rivers flowing from the mountains to the sea, which provide water for year-round agriculture and facilitate the easy transportation of goods. The Kime River and the coastal areas serve as the two most important axes of population concentration, hosting many of the country's major urban centers.

| City name | Inhabitants | Comment | Region | Cosmo City Ranking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career | Leisure | Transport | Affordability | |||||

| Pyingshum | 8,600,000 | capital and primate city | Pyingshum-iki | B | A | B | F | |

| Finkyáse | 2,435,600 | second largest urban area | Fóskiman-iki | A | A | B | D | |

| Yoyomi | 1,464,500 | largest city in the east with landmark castle | Wāfyeíkko-iki | B | A | B | D | |

| Jaka | 1,210,000 | largest harbor | Pacchipyan-iki | B | B | B | E | |

| Busakyueng | 840,000 | Kyoélnain-iki | A | B | C | E | ||

| Womenlū | 780,000 | Fóskiman-iki | B | B | B | D | ||

| Kwaengdō | 760,000 | Cheryuman-iki | C | C | C | D | ||

| Wenzū | 650,000 | spa city | Wāfyeíkko-iki | B | C | C | D | |

| Manlung | 590,000 | center for the east | Lainyerō-iki | C | C | B | C | |

| Oreppyo | 580,000 | Lainyerō-iki | C | C | C | B | ||

| Hetta | 440,000 | Pacchipyan-iki | B | C | C | D | ||

| Ántibes | 400,000 | Fóskiman-iki | C | B | C | D | ||

| Kahyuemgúchi | 370,000 | Pyingshum-iki | C | C | C | C | ||

| Nároggul | 355,000 | Degyáhin-Kibaku Yuwantsūm-Shikime-iki | C | C | C | C | ||

| Góhomi | 340,000 | skiing, sanatoriums, and health resorts | Kyoélnain-iki | B | B | C | D | |

| Geryong | 320,000 | Sappaér-iki | D | C | C | B | ||

| Ojufyeng | 260,000 | Pacchipyan-iki | B | C | B | D | ||

| Rō | 255,000 | historic, holy city of the faith Gitaenhōlyuē | Rō-iki | B | A | D | D | |

| Kippa | 250,000 | part of Kime-Yuwan industrial agglomeration | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | D | C | B | B | |

| Formajiá | 236,100 | Pyingshum-iki | B | C | B | D | ||

| Zúkshi (F. h.) | 235,000 | Fóskiman-iki | C | B | C | D | ||

| Leshfyomi-sul | 225,000 | Degyáhin-Kibaku Yuwantsūm-Shikime-iki | C | B | B | C | ||

| Toefyei | 225,000 | "Kojo's most boring city" | Wāfyeíkko-iki | D | F | C | C | |

| Tsuyenji | 220,000 | expensive summer holiday destination | Cheryuman-iki | C | A | C | E | |

| Kimelíngsan-shu | 215,000 | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | C | D | C | C | ||

| Tamrong | 210,000 | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | C | D | C | C | ||

| Púlmaerong | 205,000 | part of Kime-Yuwan industrial agglomeration | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | D | C | B | B | |

| Igilaē | 195,000 | seat of the Constitutional Court | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | B | B | A | D | |

| Arákkanai | 193,800 | Wāfyeíkko-iki | C | B | B | C | ||

| Tinglyū | 194,000 | Chin'yaku-iki | A | A | B | C | ||

| Kari | 180,000 | Wāfyeíkko-iki | D | E | C | B | ||

| Unzai | 165,000 | Kyoélnain-iki | B | C | F | C | ||

| Toribiri | 160,000 | winter sports destination and mining | Nainchok-iki | C | B | D | D | |

| Chin-Jōrin | 150,000 | Nainchok-iki | C | D | C | B | ||

| Īme | 150,000 | Chin'yaku-iki | C | D | D | C | ||

| Hóshumsul | 145,000 | part of Kime-Yuwan industrial agglomeration | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | C | D | C | B | |

| Laófil | 135,000 | Pyingshum-iki | C | E | C | C | ||

| Shangmē | 135,000 | Nainchok-iki | C | C | C | B | ||

| Láoféi | 130,000 | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | D | C | B | C | ||

| Palda | 120,000 | Lainyerō-iki | E | E | C | A | ||

| Rajjihaim | 120,000 | part of Kime-Yuwan industrial agglomeration | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | E | F | C | A | |

| Zúkshi (C. h.) | 115,000 | Cheryuman-iki | C | B | C | C | ||

| Línai | 110,000 | at mouth of pristine mountain lake | Chin'yaku-iki | C | C | C | B | |

| Maikulā | 110,000 | Pyingshum suburb with former royal palace | Pyingshum-iki | B | C | B | C | |

| Makalasueng | 105,000 | Kyoélnain-iki | C | D | B | C | ||

| Jippun | 105,000 | Lainyerō-iki | D | E | D | A | ||

| Duēkain | 105,000 | part of Kime-Yuwan industrial agglomeration | Gyoéng'guffe-iki | D | C | C | B | |

| Kōnil | 100,000 | Lainyerō-iki | C | E | D | B | ||

History

Prehistory

- ca. 7,000 B.C.: Earliest housing and farming facilities date back to this period, indicating the spread of sedentarism from central Uletha to the Axian peninsula.

- Stone Age: Tribal structures existed throughout modern Kojo. Various findings include ancient tools, cave drawings, and primitive clothing, but no recorded writing.

1st Rō-Era (Kon'yo Darasushan)

- 313 A.D.: Earliest known written document in Kojo, describing a sacrificial ritual, marking the beginning of the Kon'yo Age (Kon'yo being the name of the village close to Rō were the documents were found). Discovered in 1796. Newer research suggest it might be up to 200 years older. The fact that the ritual was described in a normative way and with emphasis on what types of fees worshippers had to hand over is proof of the emergence of complex societal structures.

- Until 614: Rō remains the most economically productive center in the region for the coming centuries, forming the first larger urban settlement and excerting cultural influence over most of the eastern half of modern Kojo, yet no direct political power.

PH-Era (Kyómre Darasushan)

- 614-876

2nd Rō-Era (Gnō Darasushan)

- 876: Local representatives congregate in Rō (Gnō) to establish a unified set of Symvanist teachings and rituals. However, modern historians agree that at the time, the tribes that congregated only accounted for a small minority of the total populace in the region, and that the agreement did not have wide-felt impacts on the religious practices and daily lifes. Instead, it was most likely just a festive side-event to the more politically motivated alliance-building, with its role for Kojolese history being exaggered in the centuries later on.

- Next 300 years: further spiritual and organisational consolidation of Symvanism, its spread across the country, and the (re-)emergence of Rō as the major religious and cultural, and also growingly economic and political centre.

Yoyomi-Era (Yochomryi Darasushan)

- Around 1200: other regions and city start eclipsing the importance of Rō, mostly due to limited arable land around the city and its geographic isolation. Economic and political power decentralises.

- Around 1250: Yoyomi (then Yochomryi), capital of the Zerka kingdom, wins the PH war against PH, which where supported by Rō, marking the symbolic end of Rōlese primacy. Despite the undoubtful dominance of the Zerka kingdom and its capital during the following centuries, many other kingdoms of almost equal status existed. This period is sometimes referred to as the dark age, because albeit general living standards not beign systematically worse compared to the previous age (though large regional and temportal differences should be noted), the 2nd Rō-age produced a much bigger cultural heritage in the form of art, poetry, and spirituality, resulting in that age being viewed as a cultural highpoint in hindsight.

The Thousand Kingdoms' War and Kojolese Unification

- 1620: Beginning of the Thousand Kingdoms' War, escalating from numerous small conflicts. Partly caused by the conflict and partly by unfavorable climate conditions, two great famines forced large parts of the population to relocate between regions, further increasing chaos.

- 1622: Surb Rēkku, King of the Pyilser-kun'a Kingdom seated in Pyingshum, being 20 years old and four years into his reign, marries Nihonese Princess Chihaya Nabunga. The marriage to Nihonese royalty not only had a vast influence on rules and rites in the royal court itself, but also drew, in addition to the already quite extensive court society, a considerable number of Nihonese migrants, accelerating as the Pysiler-krun'a's dominance over the other Kojolese regions solidified. That had a significant impact on the the Kojolese language and culture, evident for example from many loan words, predominantly in the Kēikishi registry.

- until 1668: The Pyilser-krun'a kingdom under Surb Rēkku consistenly expand their kingdom, either by military conquest or by voluntary submission of local chiefs and kings in exchange for local administrative power. In 1668, four years before Surb Rēkku's death at the age of 70, the Kingdom's territory is functionally identical to the modern Kojolese nation state.

High Pyilser-krun'a Dynasty

- 1668-1828: Although the Pyilser-krun'a dynasty ensured their control over the newly acquired territories by instituting feudal lords and controlling instead of replacing local power structures, Pyingshum became the cultural and economic center of the new kingdom. The time since 1668 is therefore sometimes collectively referred to as the "Pyingshum-age" of Kojolese history. Also during this age, the different local cultures and Pyilser-languages that had been mixed by the war, famine and big migration slowly consolidated, resulting in modern Kojo's more uniform culture and language.

1828 until 1834: Revolution and downfall of the monarchy

- 1828: As the first vibe of industrialization swept through the country, social problems became apparent. The emerging urban working class was suffering under their bad living and working conditions. Their ruler's way of spending enormous amounts of money on splendour and luxury was perceived as a sign of incompetence and extravagant at best, and malice at worst. After rising tensions, spread of antimonarchist material such as leaflets and eventually civil-war-like states in some industrial neighbourhoods throughout the country, the worker's uprising eventually overthrew the ruling King Surb-Racchi and his local aristocratic administrations. It was decisive to the success of their undertaking that the military collaborated with them during the last days of the revolution and especially during the raid on the palace. Surb-Racchi was executed, and the following years were marked by a power-struggle between the democratic and partially socialistic movements on one side and the military forces on the other, at times again under civil-war like conditions.

- 1834: After years of unrest, a semi-democratic constitution is proclaimed.

First Constitution

- 1849: It took several years for the effects of the democratic revolution in Pyingshum to spread through the country and reach the more distant regions. One reason was that the new democratic order reinstated some of the local aristocrats previously appointed by the King as governors as a way to calm and control the military throughout the nation. However the new centralistic state did not intend to prolong the tradition of granting the local posts of power to the previous office holder's descendant, but instead aimed for local administrations more closely aligned with the democratically elected national government. Throughout the first decades of the new rule, many reinstated local chiefs tried to resist this slow transfer of power away from hereditary rule and abolition of nobleness, which caused a number of state crisis's and even small armed conflicts. Only in 1859, the last hereditary local ruler was replaced by a bureaucrat appointed by the central government. This achievement was aided by the rapid growth of railways, which, besides now being the driving force behind industrialisation, enabled the government to more effectively control the outskirts of its territories.

- 2nd half of the 19th century: Power further centralised in the capital Pyingshum. Industrialisation now was transforming the economy there and elsewhere at a rapid pace and drew the masses towards the country's growing urban areas. Social norms and ideals were shifting as a consequence. Religious adherence plummeted, and by the turn of the century less than half of the population was describing themselves as active performers of Symvanism.

Second Constitution

- 1939: The political system of the first constitution had evolved in such a way that is was marked by a strong rivalry between the office of president and his Chancellor. As the chancellor had to be approved by parliament, president and chancellor sometimes were from different ends of the political spectrum, and the president would then frequently dissolve parliament and schedule reelections. When between 1928 and 1938 there were a total of 9 re-elections, it was decided that to guarantee a functioning government, there would have to be a major redraft of the political structure. Under the new system, the president was reduced to a merely representative figure with the Chancellor holding most political power. In the same instance, the redraft of the constitution was used to get rid of parts that still alluded to the classist elements relevant during the transition phase of the young democracy and replaced by norms more fitting for the mature republic.

- 1940's: Kojo was not an active battleground in the Great War, but sided with PH and fought battles primarly in PH and PH, resulting in a death toll of XX.XXX.

- 2nd half of the 20th century: being left physically untouched by the war, post-war recovery was rapid. Living standards increased as the economy started transforming from being centered on industrial production to the service industry. With the spread of the automobile, different urban forms and a higher degree of separation between work and home became common.

- 2008: The flooding of Kalaē was the nation's deathliest natural disaster of the 21st century, with an official death toll of 2,268.

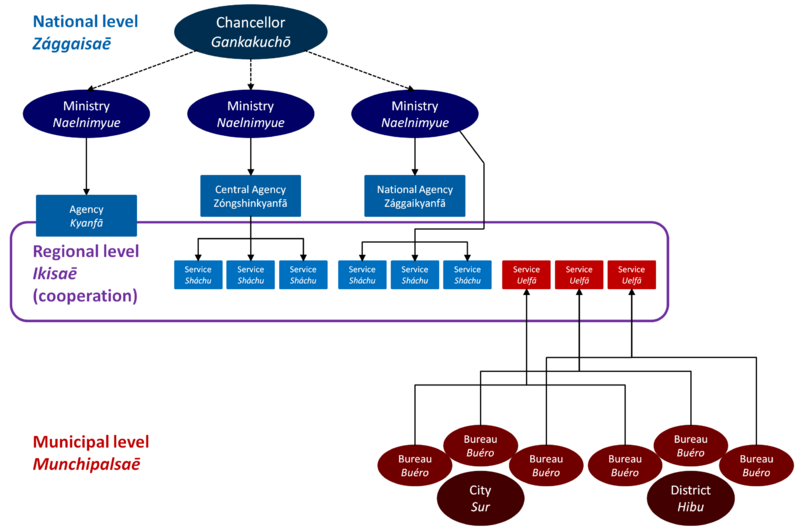

Governance

Kojo is a parliamentary and constitutional republic with a centralist state structure, meaning there are no constituent states or provinces with significant autonomy. However, the municipal level enjoys a relatively high degree of independence from the national government compared to other democratic countries. The Constitution of the Republic of Kojo divides the government into three branches: the legislative (parliament), the executive (president, chancellor, and administration), and the judiciary (courts). The "Administration" is often considered a separate, fourth pillar of the republic, as it operates with a degree of continuity and stability, even as elected governments change.

For a detailed description of the country's spatial administrative divisions, see the main article: Administrative divisions of Kojo.

President

The President (Gozóngchō) serves as the head of state and is elected by the presidential convention. The President's role is largely ceremonial, including duties such as being the highest representative of the state, appointing ambassadors, signing laws to formally enact them, and acting as a final check for constitutionality. The President serves a seven-year term and may be re-elected only once. The official residence of the President is the Presidential Mansion (Gozóngchō so Jaesan).

Parliament

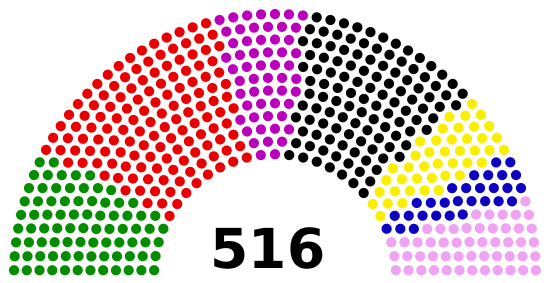

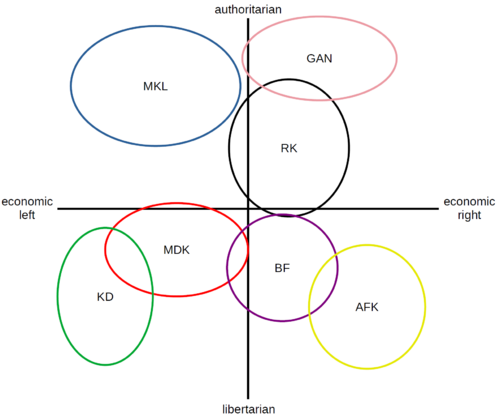

Kojo's unicameral parliament, the Jōbunhakke (lit. "People's Assembly"), is the legislative body of the nation. It is elected every four years by the people through a mixed-member proportional representation system. The parliament consists of at least 460 members, with additional leveling mandates depending on the district vote results. The primary responsibilities of the Jōbunhakke include passing laws, electing the Chancellor (Gankakuchō) at the beginning of each new term, and forming one half of the presidential convention that elects the President. In the most recent election in 2022, seven parties surpassed the 5% threshold to gain representation in parliament, though no independent candidates won a district. The election results and subsequent seat allocation are as follows:

In Kojo's parliamentary system, while laws are debated and ultimately passed by a vote in the main chamber, the bulk of legislative work is conducted in committees (Saekkai). These committees largely correspond to the government's ministries, allowing for specialized and focused deliberation on various aspects of governance. Members of Parliament (MPs) are also organized into groups (Hakkedan), typically aligned with their political party affiliation. The current legislature includes several standing committees, each composed of a specific number of members. These committees are essential for scrutinizing proposed legislation, conducting inquiries, and overseeing government operations. The list of standing committees, along with the number of members in each, is as follows:

- 01: Main Committee, 40 (Zóngsaekkai)

- 02: Petition Committee, 26 (Jōbunittai nijúinde Saekkai)

- 12: Committee for Interior Affairs, 40 (Būla nijúinde Saekkai)

- 13: Committee for External Affairs, 39 (Sotta nijúinde Saekkai)

- 14: Committee for Finances, 40 (Búkinmolno nijúinde Saekkai)

- 16: Legal Committee, 38 (Héngyi nijúinde Saekkai)

- 171: Committee for Labour and Social Affairs, 40 (Gōzo ko Myingsamolno nijúinde Saekkai)

- 172: Committee for Health and Sports, 26 (Yingmálsol ko Taigi nijúinde Saekkai)

- 18: Committee for Economic Affairs, 36 (Kishamolno nijúinde Saekkai)

- 19: Committee for Education and Culture, 36 (Goakyan ko Tsungbon nijúinde Saekkai)

- 20: Committee for Environmental Affairs, 20 (Yultai nijúinde Saekkai)

- 21: Committee for Infrastructure and Energy, 33 (Hīshíbyaeng ko Uzam nijúinde Saekkai)

- 95: Committee for Defense, 28 (Fángri nijúinde Saekkai)

- 97: Committee for Intelligence Services, 9 (Tokapparyuē so Kyanfā nijúinde Saekkai)

Municipalities' Council

Besides the Jōbunhakke, there is another legislative body, the National Municipalities' Council (Zággai Hāmaeltai Kókke, ZHK). It has a unique make up, as it is an assembly of representatives from the municipal level. Every city (sur) and rural district (hibu) casts one vote. The votes can carry different voting power according to the population, depending on the type of vote. Representatives in the ZHK are usually non-political officials of the municipality they represent and are only reimbursed for their travel and other expenses. They are bound to vote as instructed by their municipality's government. For important votes it is common that mayors or other high-ranking local politicians come to Pyingshum to cast their municipality's vote.

The ZHK's approval is needed for laws that change the financial or power relationship between local and the national government as well as changes to the constitution. In all cases when the ZHK does not approve a law proposed by the Jōbunhakke, the Jōbunhakke can schedule a popular vote which in turn can overwrite the ZHK's decision. Since the constitution doesn't provide for any other mean of changing the constitution by popular vote, there have been cases in the past where the ZHK purposefully denied approval to such a law in order to enable a popular vote, even though its members themselves were generally in favour of the change, because the matter was deemed so important that the public should vote on it. The members of the ZHK also elect the second half of the presidential convention, which in turn elects the president.

Because it only has very limited functions, the ZHK is usually not counted as a second chamber of parliament. Historically, the ZHK was never intended by the fathers of the constitution when it was written in 1834. It formed as a sort of common lobbying institution for the municipalities, to represent their interests in national politics. When the constitution was thoroughly reformed in 1939 provisions about the ZHK and the types of laws that needed its consent were codified, but to this day it is not recognised as a second chamber of parliament. After the great fire of 1984 and during the subsequent rebuilding of a part of the government quarter in Gankakuchō-Pang, a representative building was erected for the ZHK just north of the Chancellery.

Chancellor

The Chancellor (Gankakuchō) is the head of government. They are not elected by the people, instead after parliamentary elections the Jōbunhakke elects a Chancellor with a simply majority of its members. Usually, they are leader of the strongest political party in the new government. The Chancellor appoints the rest of the government, most importantly the ministers, by formally suggesting them to the President, who then has to appoint them. The Chancellor is traditionally the single most influential person in politics, since they define the guidelines of inner and foreign policy. Due to historical reasons, they come 3rd after the president and the president of the parliament in official state protocol. This also reflects in the location of the Chancellery (Gankakuchō so Hyosilwe), located in Pyingshum's Gankakuchō-Pang, which is less prominent than those of the presidential mansion or parliament.

The current incubent is 52 year-old Madelaén Sáku (MDK). She was first elected in 2016 and re-elected twice since then. She is the second woman to hold this office after Ushira Tsungmaéi (RK) from 2004 to 2008, and the first one not born a Kojolese citizen; her parents immigrated from Khaiwoon in 1973 when she was 5 years old.

Administration

A rather unique feature of the Kojolese political system is the emphasis on a strict border between the government and "The Administration" (Dáhano). The administration is often cited as the 4th division of power. While the executive branch such as the Chancellor and the Ministers are mostly focused on drafting laws and enacting policy in their respective fields, these policies are then executed by the various national, regional and municipal agencies. Although the various agencies are under the direct control of either the national or respective municipal government(s), they are said to exhibit a life on their own. The way policies are enacted in practicality is strongly shaped by the administration's own way of doing things.

Career paths in the administration usually start in municipal or regional agencies, with aspirants working their way up through the regional or national agencies. Very successful high school or university graduates are also sometimes recruited directly into higher ranks, especially after graduating from the prestigious and hard to get into School of Higher Administration (Kōkumin Ekól). It is estimated that among leadership positions in the regional and national administration (excluding the ministries themselves), ca. 70 % have worked up their way from entry-level positions, 25 % are Kōkumin Ekól graduates and only another 5 % are career changers who have worked outside of the administration for some time. Unlike in a lot of other democracies, the Kojolese constitution knows a number of cases where the passive suffrage is restricted: anyone employed in the national or regional administration cannot run for office in national elections for 5 years after their last day of employment, extending to 10 years for positions of leadership. Similarly, many municipalities also use their constitutional right to institute such regulations on a municipal level.

The following list only includes civil services provided by the national government and its regional embodiments. The municipal administration and their bottom-up counter parts on the regional levels (such as garbage, public order offices, schooling infrastructure, public transportation etc.) as well as agencies not classified as part of the executive (such as the parliament administration or institutions relating to the courts' self-management) are not included. The ministries oversee a lot of different agencies and services, to which they delegate most of the technical work and interaction with the public. Besides drafting laws, the ministries most importantly set policy guidelines for their subordinate agencies. On a regional level, all agencies and services by the national government are also coordinated by the respective region's Prefect, who is appointed by the Chancellor. They are mostly responsible for managing everyday operations, advising the central government on regional matters, coordinating the agencies among each other and with the municipalities administration, appointing important leadership roles, as well as disaster relief and representing the central government in their region.

The most common name for institutions with nation-wide scope of action is Kyanfā ("Agency"). Regional institutions under national directive are called Sháchu ("Service"). Agencies which oversee regional services are amended with the prefix "Central" (Zóngshinkyanfā), while Agencies with no oversight over the corresponding regional Services (because they are directly controlled by the ministry as well) usually bear the title "National" (Zággaikyanfā). The aforementioned naming scheme only applies to the administration under the directive of the national government. City departments or offices are usually called buéro, while agencies instituted on the regional level but operating under the directive of the respective region's municipalities are called uelfā. While most agencies and services are referred to using an abbreviation of their full name in everyday use, there are inconsistencies regarding their long-name variants. While some names include grammatical particles to emphasizes their respective grammatical function (Shínchopō sum shárukanyaesói so Kyanfā, lit. "Agency for Protecting the Constitution"), other names do not (Oetsōno Kyanfā, lit. "Migration Agency").

- National administration:

- Office of the Presidential bureau (Gozóngchō so Hyokyanfā, Pyingshum)

National Auditing Authority (Zággai Búkinshutugēl Sanzyofā, Pyingshum)

National Auditing Authority (Zággai Búkinshutugēl Sanzyofā, Pyingshum) Constitution Protection-Agency (Shínchopō sum shárukanyaesói so Kyanfā (SHSHK), Pyingshum)

Constitution Protection-Agency (Shínchopō sum shárukanyaesói so Kyanfā (SHSHK), Pyingshum) Kojolese Central Bank (Kojo Zóngshin-weibyaeng, Pyingshum)

Kojolese Central Bank (Kojo Zóngshin-weibyaeng, Pyingshum) National Archive (Zággai Altífōwe, Pyingshum)

National Archive (Zággai Altífōwe, Pyingshum)- Chancellor (Gankakuchō, Pyingshum)

- The Chancellery (Gankakuchō so Hyosilwe, Pyingshum)

- Office of the Press Secretary

- Officer of State for Digital Affairs

- Officer of State for Relations with the Arkatsum Kingdom

- 13 Prefects (Maekkyosil)

Ministry of the Interior (Būla so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of the Interior (Būla so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Administrative Issues

- Central Police Agency (Atóm'yi Zóngshinkyanfā, Duēkain)

- 13 regional Police Departments

- Central Criminal Prosecution Agency

- 22 Police Academies

- Customs Office

- Agency for Digital Security

- Agency for Meteorology

- National Agency for Monument and Landscape Conservation

- 13 regional Monument and Landscape Conservation Services

- 15 regional Archives

- Agency for Migration (Oetsōno Kyanfā, Kwaengdō)

- National Agency for Civil Protection and Disaster Prevention

- Agency for Technical Assistance

- 11 regional Technical Relief Services

- Central Agency for Spatial Planning, Mapping and Interregional Cooperation (Wamzudamolno, Nomshusói ko Mijidōdaeki Kyakkai Zóngshinkyanfā, Jaka)

- 13 regional Spatial Planning Services

- Agency for Volunteer Service (Kámpō Ashkan Kyanfā, Pyingshum)

- Agency for National Elections (Zággaitsūn Kyanfā, Unzai)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Sotta so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Sotta so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Foreign Intelligence Agency (Dózai-Tokapparyuē so Kyanfā (DTK), Pyingshum)

- Agency for the Promotion of Kojolese Culture and Language Abroad

- Embassies of Kojo abroad

Ministry of Finance (Búkinmolno so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Finance (Búkinmolno so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Financial Services Certification

- National Agency for Taxation (Harkai nijúinde Zággaikyanfā, Hóshumsul)

- 13 regional Taxation Services

- xxx local collection offices (Búkinfā)

- National Agency for Remuneration

- 13 regional Remuneration Services

- National Agency for National Asset Management

- 13 regional Asset Management Services

Ministry of Defence (Fángri so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Defence (Fángri so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Kojolese Military (Kojo so Forsamé, Hittouel)

- Military Counter-Intelligence Agency (Fanglyué-Jōto so Kyanfā (FJK), Pyingshum)

- 2 Universities of the Armed Forces (Forsamé so Ōnagara, Pyingshum and Jaka)

- Agency for Acqusition

Ministry of Justice (Héngyi so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Justice (Héngyi so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency of Justice (Héngyi so Kyanfā, Pyingshum)

- Central Agency for Consumers' Rights

- 13 regional Consumers' Rights Services

- Public Prosecutor's Agency

- 13 regional Public Prosecution Services

- 12 regional Penitentiary and Resocialisation Services

Ministry of Labour, Social Issues and Sports (Gōzo, Myingsamolno ko Taigi so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Labour, Social Issues and Sports (Gōzo, Myingsamolno ko Taigi so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Work (Ashkan Kyanfā, Púlmaerong)

- Ribal Kecskés Institute for Transmissible Diseases (Ribal Kecskéskaso roenglanzáu Yokkae nijúinde, Pyingshum)

- Central Agency for Public Health

- 12 regional Public Health Services

- Agency for Drug and Medical Services Certification

- Agency for the Advancement of Competitive Sport (Mankaidaeki Taigi so Yaeshittehīchon lui Kyanfā, Jaka)

- 7 regional athletes' contact bureaus

- Agency for Workers' Protection

- Oversight-Agency for the five obligatory insurance services (Hizo Akken sum Elpyaenfi-Kyanfā, Tinglyū)

- Care Agency

- Agency for Family

- Anti-discrimination Agency

- Central Agency for Youth

- 13 regional Youth Services

- Media Inspection Agency

Ministry of Economic Affairs and Trade (Kishamolno ko Jijiyaengmolno so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Economic Affairs and Trade (Kishamolno ko Jijiyaengmolno so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Patents and Trademarks

- Agency for Statistics

- Agency for Import and Export Monitoring (Jaka)

- Cartell Agency

- Agency for Food Safety

- Agency for Caration and Standardisation

- Agency for Mining and Pitmen

- Agency for Professional Training

- Agency for Funds Distribution and General Affairs

Ministry of Education, Innovation and Culture (Goakyan, Líno ko Tsungbon so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of Education, Innovation and Culture (Goakyan, Líno ko Tsungbon so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Public Health Education

- Agency for Political Education

- National Library (Zággai Besoegawan, Pyingshum)

- 21 Central Libraries

- 5 National Museums (Jōbun-Showugan, "People's Museum": two in Pyingshum (History, Art), one in XX (Science and Technology), XX (Sport) and Yoyomi (Geology))

- National Agency for the Coordination of Vocational Training

- 13 regional bureaus for the Coordination of Vocational Training

- Agency for Pre-natal care, Daycare and Preschool

- Agency for Primary and Secondary Schooling

- Oversight-Agency for Higher Education

- Central Agency for Archaeology

- 13 regional Archaeology Services

- National Agency for Conservation of the Intangible

- 13 regional Services for Conservation of the Intangible

- Agency for Material Acquisition and Distribution (Sowenlichidoemsol so Mishisói ko Otamishisói lui Kyanfā, Shīmau)

- Kojolese Research Funding Society

Ministry of the Environment (Yultai so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

Ministry of the Environment (Yultai so Naelnimyue, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Nuclear Safety and Disposal

- National Agency for Environmental Research

- 13 regional Environment and Sustainability Services

- Central Agency for Woodlands, Ranching, Hunting and Firearms

- 12 regional Forestry and Ranching Services

- 12 regional Hunting Services

- 59 regional Firearm Services

- Central Veterinary and Animal Welfare Examination Agency

- 38 regional Veterinary and Animal Welfare Examination Services

Ministry of Infrastructure, Communication and Energy (Hīshíbyaeng, Denching ko Uzam so Naelnimyue)

Ministry of Infrastructure, Communication and Energy (Hīshíbyaeng, Denching ko Uzam so Naelnimyue)

- Aviation Agency (A'érosaē so Kyanfā, Pyingshum)

- Lower Agency for Air Traffic Control "Kojocontrol" (Aensaē Ishkel Bangfā, Pyingshum)

- Lower Agency for Aircraft, Aerodrome and Personnel Certification (Aenlai, A'éropō ko Rinin so Shataeiyusói Bangfā, Pyingshum)

- Agency for Waterways and Shipfare (Hún'gō ko Champyonsaē Kyanfā, Kippa)

- Agency for Roads (Michi Kyanfā, Kippa; research institution)

- National Agency for Planning, Construction and Upkeep of Motorways

- 12 Regional Road Planning, Construction and Upkeep Services

- XX motorway maintenance facilities (Kōfogótsu Zoékasóijo)

- Road Approving Agency (licensed, private company owned by the government)

- Motor Vehicles Admission Board (licensed, private company owned by the government)

- Agency for Railway Infrastructure and Operation (research institution)

- Agency for Railway Certification (licensed, private company owned by the government)

- Kojo Railway Company (Kojo Hyengshō Sanan, non-licensed, private company owned by the government)

- Agency for Signal Communication

- Agency for Post Affairs

- Agency for Energy Production, Subsidies and Emission Certificate Trade

- Agency for dams and Hydroelectricity

- Agency for the Power, Gas and Water Networks

- Central Agency for Communication and Data Networks

- 10 regional Data Networks Services

- Agency for Passenger and Freight Transport (regulatory authority)

- Aviation Agency (A'érosaē so Kyanfā, Pyingshum)

Municipal Level

The Kojolese constitution defines the scope of responsibility for the national government on one hand (handled by the agencies listed above), and the municipalities (surs and in the case of rural areas hibus and Pangs, each with their own respective administration) on the other. In general, laws and regulations are always enforced by the same level that also sets the relevant rules, with some exceptions (most notably devolved duties). The following list give an overview over the competences at the national and local:

Competences of the national level are constitutionally restricted to:

|

Competences of the municipal level (surs, hibus, pangs) encompass everything not assigned to the national government, commonly:

|

The national level can generate income through every mean not reserved to the local level, commonly:

|

The means the municipal level can generate income are constitutionally restricted to:

|

Municipalities' legal rights or obligations can be classified into one of three "classes of sovereignty". A municipality's right to set the rules regarding its own elections (within the democratic principles of the constitution) or veto a change to its boundaries are core principels of municipal sovereignty. No simple law passed at the national level, even if approved by the ZHK, can strip an individual municipality of such rights. The only, though quite hypothetical way to amend this would be a change to the constitution's definition of those core principles.

One step further down the line there are the (simple) constitutionally granted sovereignties. They for example include the types of taxes municipalities can levy or what areas of law and public order they can regulate. To make changes to such issues, a law must pass the Jōbunhakke with a simple majority and the ZHK with a dual majority (both majority of population and entities).

Lastly, there are laws that indirectly affect the municipal level (regulatory and/or financially), but do not infringe on their sovereignties. Those include laws that devolve administrative functions from the national government to the local governments, such as changes to the social welfare system which is in part carried out on the local level by the municipalities. Also, environmental laws that are enforced by municipalities or changes to education standards like requiring Wifi in school buildings would fall in this category. Besides a simple majority in the Jōbunhakke, such laws also need a popular majority in the ZHK (meaning that surs and hibus representing at least half of the Kojolese population approve).

Due to the fact that municipalities are autonomous in regard to their internal affairs, there is wide variety in the way they structure their administration and politics. For example, there is an unmanageable diversity of local electoral law, especially among smaller towns and villages. While every municipality is bound by the democratic principles laid out in the constitution, they are free as to how to embellish them. Among exceptionally small villages it is common to elect a mayor by a majority vote, sometimes with and sometimes without run-offs, and to not have a local council elected alongside. Places that do elect local councils do so using many different kinds of voting procedures, from systems using electoral districts and a first-pass-the-post-approach to mixed-member proportionate party lists systems with multiple transferable candidate and list votes per voter.

Regional Level

Kojo is a centralist state, with elections only taking place at the national and the municipal level. The 13 intermediate regions ("Iki") are a stage for balance of interest and cooperation. The national government's (top-down) Iki-administration is headed by a prefect, who is appointed by the Chancellor. The prefects execute the central government's policies in their respective regions and manage the regional services (Sháchu). In the numerous areas overlapping with the municipalities' jurisdiction, the prefect frequently serves as a local negotiator. They are also responsible for imminent relief in the case of catastrophes and are only allowed to leave their Iki when instructed to do so by the central government. On the local side, municipalities coordinate their efforts on the Iki-level bottom-up to voice their interests to the national government and seize synergies. The degree to which this happens varies: in some regions, a large bureaucracy jointly controlled by the municipalities does a lot of everyday administrative tasks, such as transit planning, preservation or healthcare. In others, those matters are dealt with by each individual municipality and their common regional administration only facilitates voluntary coordination and lobbying. For an in-depth explanation and complete list of lower levels of subdivision, please refer to the main article: Administrative divisions of Kojo.

| Name | ID | Area | Population | Pop. density [inh./km2] | Prefecture seat | Cities

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyingshum-iki∈⊾ | KO-01 | 11984.7 | 12,124,000 | 1000 | Pyingshum | Pyingshum, Kahyuemgúchi, Formajiá, Laófil, Maikulā |

| Gyoéng'guffe-iki∈⊾ | KO-09 | 18830.5 | ca. 3,500,000 | x | Láoféi | Kimelíngsan-shu, Tamrong, Kippa, Igilaē, Púlmaerong, Hóshumsul, Láoféi, Rajjihaim, Duēkain |

| Kyoélnain-iki∈⊾ | KO-05 | 37600.5 | ca. 1,800,000 | x | Busakyueng | Busakyueng, Góhomi, Unzai, Makalasueng |

| Nainchok-iki∈⊾ | KO-06 | 33222.4 | ca. 1,000,000 | x | Toribiri | Toribiri, Chin-Jōrin, Shangmē |

| Sappaér-iki∈⊾ | KO-08 | 7476.2 | ca. 680,000 | x | Geryong | Geryong |

| Fóskiman-iki∈⊾ | KO-10 | 7315.1 | ca. 5,500,000 | x | Finkyáse | Finkyáse, Womenlū, Ántibes, Zúkshi (Fóskiman h.) |

| Lainyerō-iki∈⊾ | KO-07 | 105280.5 | ca. 2,700,000 | x | Manlung | Manlung, Oreppyo, Palda, Jippun, Kōnil |

| Pacchipyan-iki∈⊾ | KO-11 | 3079.7 | ca. 3,300,000 | x | Jaka | Jaka, Hetta, Ojufyeng |

| Degyáhin-Kibaku Yuwantsūm-Shikime-iki∈⊾ | KO-02 | 10308.4 | ca. 3,000,000 | x | Kimaéchul | Nároggul, Leshfyomi-sul |

| Chin'yaku-iki∈⊾ | KO-04 | 5875.3 | ca. 1,700,000 | x | Tinglyū | Tinglyū, Īme, Línai |

| Rō-iki∈⊾ | KO-13 | 95.4 | 255,000 | 2672 | Rō | Rō |

| Wāfyeíkko-iki∈⊾ | KO-12 | 16319.5 | ca. 4,500,000 | x | Yoyomi | Yoyomi, Wenzū, Toefyei, Arákkanai |

| Cheryuman-iki∈⊾ | KO-14 | 5896.3 | ca. 2,000,000 | x | Kwaengdō | Kwaengdō, Tsuyenji, Zúkshi (Cheryuman h.) |

Courts

|

The courts form the judiciary and are independent. The supreme court and two of five courts of last appeal are situated in the city of Igilaē, with the other three national courts also situated in cities other than the capital Pyingshum, in order to physically represent the independence of the Judiciary from the other branches of government.

The constitutional court (Shínchopō nijúinde Dattarān, lit. "Supreme court about the constitution", situated in Igilaē) has the last say in all controversies over the constitution. The other courts of last appeal are all responsible for a distinct area of law and can be appealed to by anyone on any legal dispute after going through the lower stages in the court hierarchy. These so called national courts are:

- Tsōbolakān nijúinde Dattarān; supreme court of ordinary jurisdiction; usually concerned with issues of civil or criminal law; Finkyáse

- Búkinmolno nijúinde Dattarān; supreme court of financial jurisdiction; concerned with taxation, customs and public finances; Igilaē; not to be confused with the central auditing authority (Búkinshutugēl Sanzyofā) in Pyingshum

- Gōzomolno nijúinde Dattarān; supreme court of labour jurisdiction; Igilaē

- Myingsamolno nijúinde Dattarān; supreme court of social jurisdiction; Tinglyū

- Tōyo nijúinde Dattarān; supreme court of administrative jurisdiction; concerned with legal disputes over administrative acts, usually between citizens and the state or between different agencies; Láoféi

The lower courts are organised on a regional (Gōsaeidaran) and municipal (Munchipaldaran) level. In the two biggest cities, Pyingshum and Finkyáse, cases of civil law or other (minor) cases can be dealt with at even more local district courts (Shottarān) instead of the municipal court. However, if the court's ruling is appealed, the case then advances to the regional court and is not again heard at the municipal court.

Military

Military expenditure accounts for 2.6 % of the country's GDP. It includes the army (Bánakin), the air force (Óduekin) and the navy (Paushil). Other subdivisions and associated agencies include the medical service, the military counter-intelligence service (Fanglyué-Jōto so Kyanfā, "FJK"), a cyber unit, strategical planning offices and more. The entirety of the armed forces are called "Kojo so Forsamé".

The Bánakin (army) consists of about 35,000 soldiers, which are organised in 52 squadrons called Zóngkai. One or several squadrons are stationed at one of 30 bases (called Kázen), not including small non-military offices for administrative purposes.

The Óduekin (air force) employs around 15,000 soldiers, organized in four tactical units, two transport units (with the one stationed in Pyingshum also having a sub-unit dedicated to government flights), two helicopter units, two ground-based air defence units and two training units. Those units are called pyoéton and are usually stationed on bases adjacent to purely military or mixed-use airports.

About 8,000 soldiers serving in the Paushil (marine) secure Kojolese territorial waters and borders. Custom and sea rescue operations are carried out by different entities. The four marine bases are called Pautang (an otherwise archaic word for harbour) and located in Zúkshi (Cheryuman h.), Jaka, Arákkanai, and PH near Zúkshi (Fóskiman h.).

Emblems

The Kojolese flag, adopted following the democratic revolution in 1834, serves as a powerful national symbol. It features horizontal stripes of blue, gold, and green, separated by white. These colors represent the country's three key landscapes: "water/coast" (blue), "crops/farmland" (gold), and "forest/mountains" (green). On the left side of the flag, a red zig-zag bar symbolizes the bloodshed during the civil war. This design element harks back to the battle banners stained with the blood of both the defeated establishment and the victorious revolutionaries. The flag is used in both official and informal contexts to represent the Kojolese nation.

The state seal of Kojo is reserved for representing the nation in its most formal and official capacities, such as on monuments, special awards, and international treaties. Variations of the state seal are used by the President, Chancellor, and Parliament for significant formal acts, such as appointing ministers, dissolving parliament, or enacting laws. The seal features a duck with a pen and hammer, symbols rooted in mid-19th-century Kojolese history. The pen and hammer represent the intellectuals' righteousness and the industrious determination of the working class, both of which were pivotal groups in the revolution and the establishment of democracy. The duck, Kojo's national animal, was chosen for its agricultural utility—controlling pests, laying eggs, and providing meat and feathers—as well as its humble and balanced nature. This symbolism, along with the national motto "By the People, for the People," underscores the Kojolese Republic's commitment to the common people, in stark contrast to the self-centered and extravagant Kojolese Monarchy. Since the 1960s, the duck has also become a humorous and endearing national symbol, often used as a mascot in visual media and sports.

Kojo's regions, or Ikis, are explicitly prohibited from using their own emblems, as all sovereignty is vested at the national or municipal levels. At the municipal level, rural Pangs, Hibus, and Surs are entitled to adopt their own flags, seals, or other emblems. Most municipalities do so, incorporating significant historical and regional symbolism into their designs. These municipal emblems reflect the diverse cultural heritage and local pride found across Kojo.

Transportation

| Infrastructure of Kojo | |

|---|---|

| Roadways | |

| • Driving side | Right |

| Railways | |

| • Passing side | Right |

| • Gauge | 1435mm |

| • Electrification | Varies |

| Telephone code | +388 |

| Internet TLD | .ko |

Key Data

At 3.5 trips per day and person, Kojo has a comparatively high average mobility rate. Reasons include high female employment, age distribution and high division of labour. The average length of a commute from home to work is 11.7 km. At 410 passenger cars per 1,000 inhabitants, car ownership in Kojo is lower than in other similarly developed countries. Mode share, that is the share of trips (not traffic volume) undertaken via a specific mode, varies strongly depending on urbanisation and other local factors.

Spatial Planning

Spatial planning encompasses two related tasks: to ensure a spatially comprehensive yet economical supply with public and private goods (from grocery stores and schools to department stores and major hospitals), and to plan the transportation network accordingly. In Kojo, spatial planning is carried out on the national level by the central government, and by the hibus and surs in cooperation with the central government on the regional level.

It is based on the Central Place Theory which categorises settlements into four categories. This categorisation does not say anything about the political status of a settlement, but defines spatial planning goals about what kinds of goods and services should be available in that place. In a second step, there are nationally and regionally defined minimum accessibility thresholds, stating that from any inhabited place, one should be able to reach the nearest place of a given category in a set amount of time. Infrastructure is then planned accordingly. This process is under regular revision, with either transportation links being improved or, if deemed more feasible, placed being recategorised into higher categories to serve an underserved area. The four categories are:

- International Node (Mijizággai Noé): Metropolises that connect the region or nation to the international economy. In Kojo, only Pyingshum, Finkyáse, the Kime-Yuwan-agglomeration, Jaka, and Yoyomi fall into this category. Airfare infrastructure is concentrated on these cities, as well as highly specialised service industries such as consulting.

- Higher Center (Hangshin): Cities that cover periodic needs, which includes amenities such as: cinema, large department store, hospital, a representation of the regional authority, theatre, higher education.

- Basic Center (Sōshin): Covers all necessities of everyday life. This includes for example: comprehensive options for grocery and some retail shopping, post office, bank, representation of the local authority (registering a car, collecting social benefits etc.), police station, library, primary and middle schools, basic medical care.

- Phone Box (Denkan): Covers the basic necessities of everyday life. The name dates back to the early days of the telephone, when the government aimed to ensure that everyone should be able to reach a public telephone in the next village by bicycle. While those are now rendered obsolete by new technologies, places of this category still need to provide residents with a post box, a small shop to purchase the most basic food items, and a bus connection to the nearest basic center at least every other hour.

Road

The road network is hierarchical, with the different types of roads indicating different design standards as well as which layer of government is responsible.

| Class | Naming | Jurisdiction | Link function | Design standard and access | Mapping | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motorways Gimbye Kōfogótsu (lit. Gimbye Highclass road) |

G ### | National Agency for Planning, Construction and Upkeep of Motorways (national funding) | Long-distance | At least two lanes per direction with structural center-barrier. Grade-separate. Tolled with some exceptions. 120 km/h, local and temporal restrictions might apply. | Red for three or more lanes per direction (motorway)

Dark orange for two lanes per direction (trunk) |

|

| Other National Roads Dōdaeki Zóngtsūfogótsu (lit. Regional main through road) |

D ### | 12 Regional Road Planning, Construction and Upkeep Services (national funding) | Interregional | At least one wide lane per direction. 50/70/100 km/h. Can exhibit motorway-like design features on heavily used sections. | Orange (primary) |  |

| Regional Roads Dōdaeki Tsūfogótsu (lit. Regional through road) |

I ### numbers unique only in each region |

Road Agency of the respective Iki (aggregate municipal funding) | Regional | At least one wide lane per direction. 50/70/100 km/h. In rare cases exhibits motorway-like design features on heavily used sections. | Yellow (secondary) |  |

| District Roads Hibu so Tsūfogótsu (lit. District through road) |

H ###, S ### numbers unique only in each Hibu/Sur |

Road Agency of the respective Hibu/Sur (municipal funding) | Link between or through settlements | At least one lane per direction. 30/50/70/100 km/h. | White, bold (tertiary) |  |

| Municipal Streets | Differs by municipality | Road Agency of the respective Pang (in Hibus, unless dependent Pang), Sur (in Surs) or Dengshō (in Pyingshum and Finkyáse) (municipal funding) | Access to adjunctive lots, no link function | Must be passable. 10/30/50/70 km/h. | White (unclassified) |  |

Motorways (G) are numbered with single, double or three digits. The numbering system is as follows:

- Single digits

- 1 - 9: main motorways for very long distance travel

- Double digits

- 11 - 19: shorter motorways in Pyingshum region

- 20 - 39: additional important long-distance motorways leading towards Pyingshum

- 40 - 59: additional important long-distance motorways not leading towards Pyingshum

- 60 - 69: shorter motorways in the center and south

- 70 - 79: shorter motorways in the west

- 80 - 89: shorter motorways in the east

- 91 - 99: short motorways leading inside the Pyingshum inner belt motorway

- Three digits

- 100: Pyingshum inner belt motorway

- 101 - 189: more shorter motorways in Pyingshum region

- 600 - 689: more shorter motorways in the center and south

- 700 - 789: more shorter motorways in the west

- 800 - 889: more shorter motorways in the east

- 900 - 989: special (as of now, only airport loops)

- X90 - X99: disconnected sections of a main motorway starting with X

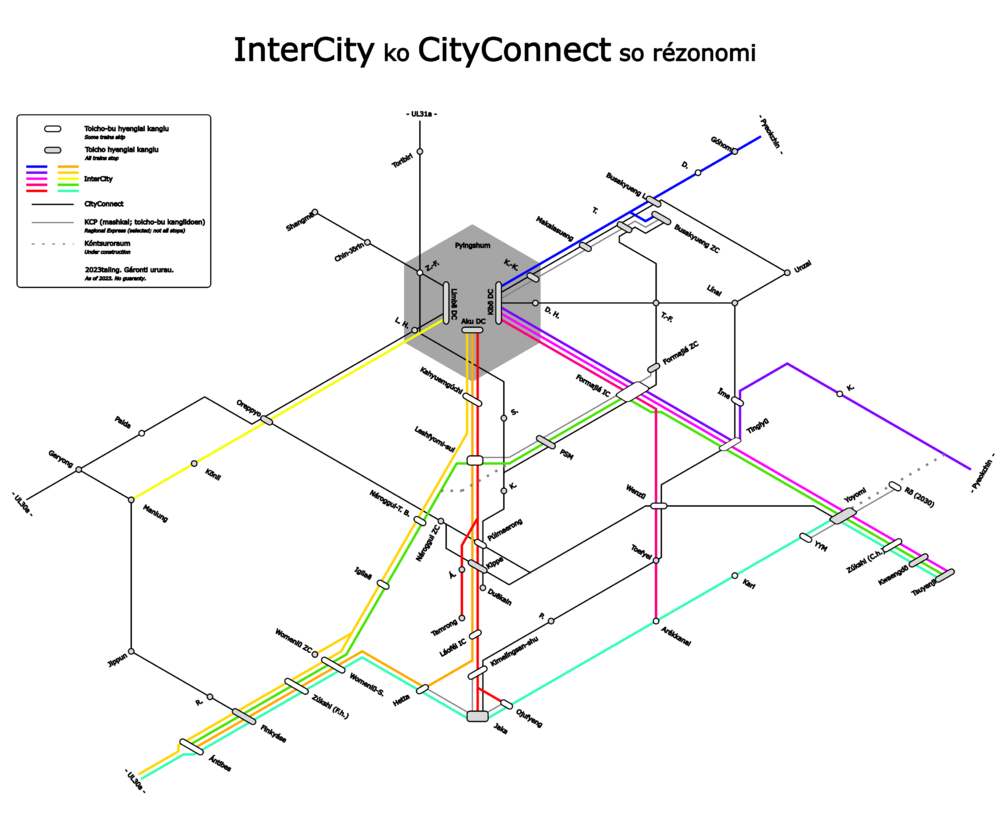

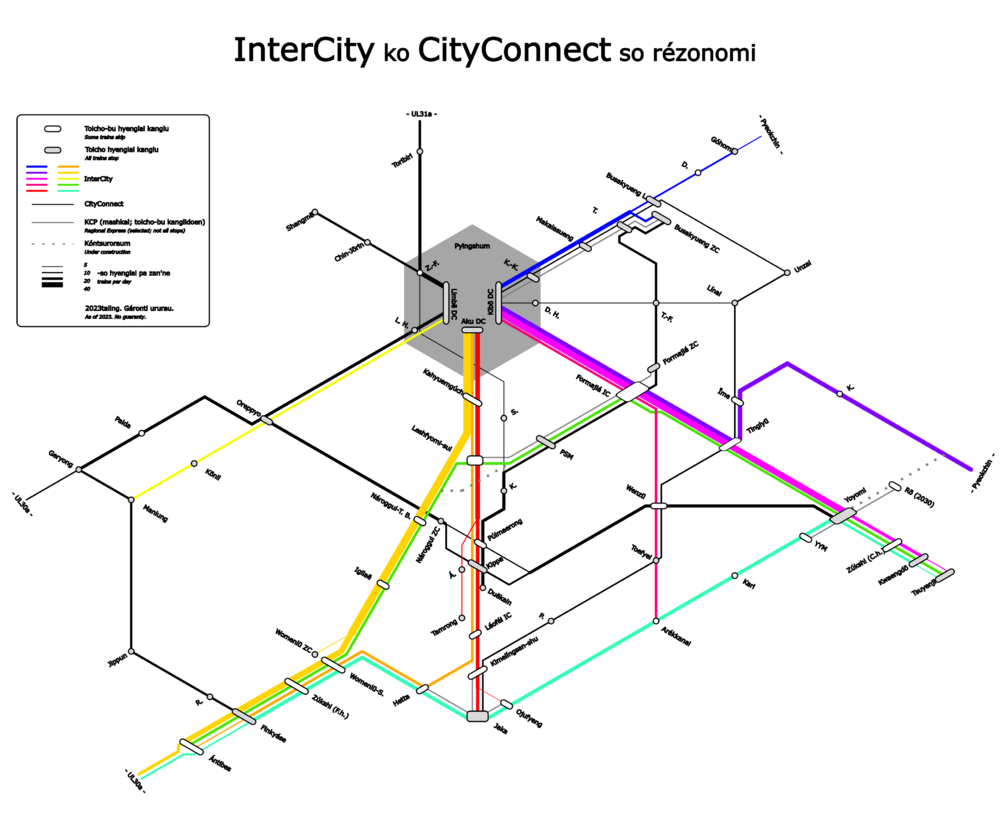

Rail

Kojo has a dense and highly utilised railway network with a wide range of passenger rail services and freight operations. They are for the most part operated by state-owned Kojo Hyengshō Sanan ("Kojo Railway Company", KHS). Around 80 % of track-kilometres are electrified. With few exceptions such as mountain railways, railways operate on standard gauge.

| Name | Fare | Stopping Pattern | Maximum Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| InterCity

(IC) |

Demand-responsive | Only calls at major cities (usually at least 100,000 inhabitants). Some Sprinter-services offer non-stop connections between major metropolises, skipping even more intermediate stops. | 280/300/320 km/h on dedicated tracks, depending on rolling stock |

| CityConnect

(CC) |

Calls at major cities and regional centers. | 200/250 km/h on dedicated tracks, depending on rolling stock, often lower on tracks shared with freight and regional trains | |

| Kūyú-chegicha Papáchē

(Regional Rail Express, KCP) |

Local transit pricing scheme | Only calls at large towns and the most important stations in major cities. | 160/200 km/h in some exceptions, 250 km/h when using IC tracks |

| Kūyú-chegicha Soémipapáchē

(Regional Rail Semi-Express, KCS) |

KC-like stopping pattern on one and KCP-like stopping pattern on the other part of its route. Usually used in the commuter belt of large cities. | 120/160 km/h, lower on curvy sections | |

| Kūyú-chegicha

(Regional Rail, KC) |

Calls at every stop. | 120 km/h, lower on curvy sections |

IC & CC Services

| Train No. | Terminus | via | Terminus | t/d, dir. | Rolling stock | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Púlmaerong, Kippa, Láoféi IC, Kimelíngsan-shu | Jaka | 7 | (5+5) | |

| 13xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Kippa | Jaka | 8 | (5S+5) | |

| 14xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Kahyuemgúchi, Leshfyomi-sul, Ámrotse | Tamrong | 8 | (3) | |

| 15xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Leshyomi-sul, Púlmaerong, Kippa, Láoféi IC, Kimelíngsan-shu | Jaka | 9 | (5+5), (3) | |

| 18xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Kippa | Ojufyeng | 4 | (4+4) | |

| 16xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Kippa, Hetta, Womenlū-S. | Finkyáse | 11 | (5S+4) | |

| 17xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Kahyuemgúchi, Leshfyomi-sul, Kippa, Láoféi IC, Hetta, Womenlū-S., Finkyáse | Ántibes | 10 | (4+4) | |

| 20xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Finkyáse, (Ántibes,) | -UL30a- | 24 | (5S+5S) | GoldStar |

| 22xxx | Pyingshum ADC | - | Finkyáse | 8 | (5S+5) | |

| 23xxx | Pyingshum ADC | - | Womenlū ZC | 6 | (5+5) | |

| 24xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Kahyuemgúchi, Nároggul-T. B., Igilaē, Womenlū-S., (Zúkshi (F. h.),) Finkyáse | Ántibes | 15 | (4+4) | |

| 29xxx | Pyingshum ADC | Womenlū-S., Zúkshi (F. h.), Finkyáse, | Ántibes | 6 | (3) | spring and autumn holiday |

| 31xxx | Pyingshum KDC | - | Yoyomi | 22 | (5S+5) | |

| 33xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.), Kwaengdō | Tsuyenji | 8 | (5S+5) | |

| 34xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Formajiá IC, (Tinglyū,) Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.) | Kwaengdō | 17 | (4+4) | |

| 36xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Formajiá IC, Tinglyū | Jukoel - Rō Limbē | 2 | (4+4) | |

| 39xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Tinglyū, Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.), Kwaengdō | Tsuyenji | 4 | (3) | spring and autumn holiday |

| 41xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Formajiá IC, Duma - Wenzū ZC, Toefyei | Arákkanai | 19 | (3) | |

| 50xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Tinglyū, Namgyeong/남경, Jungpo/중포부, Nagareki/沼浦, Reilusahna/清浦, (Shirukami/荒釜,) (Sahnajima/灣湧) | Sainðaul/作安崎 | 18 | (5S+5S) | Minarajaki |

| 51xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Formajiá IC, Tinglyū, Īme, Kyungwelsul (b. h.), PH/…, PH/… | Namgyeong/남경 | 16 | (5S+5) | Minarajaki |

| 60xxx | -UL30a- | Finkyáse, Jaka, Yoyomi, Kwaengdō | Tsuyenji | 8 | (5S+5) | |

| 61xxx | -UL30a- | (Ántibes,) Finkyáse, Jaka | Yoyomi | 8 | (5S+5S) | |

| 63xxx | Ántibes | Finkyáse, Zúkshi (F. h.), Womenlū-S., Hetta, Jaka, Ojufyeng, Arákkanai, Kari, YYM, Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.) | Kwaengdō | 6 | (4+4) | |

| 64xxx | Finkyáse | Womenlū-S., Hetta, Jaka, Arákkanai, YYM, Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.) | Kwaengdō | 6 | (4+4) | |

| 69xxx | -UL30a- | Ántibes, Finkyáse, (Zúkshi (F. h.),) Womenlū-S., Hetta, Jaka, Arákkanai, YYM, Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.), Kwaengdō | Tsuyenji | 6 | (4+4) | spring and autumn holiday |

| 71xxx | Ántibes | Finkyáse, (Zúkshi (F. h.),) Womenlū-S., (Igilaē,) Nároggul-T. B., Leshfyomi-sul, PSM, Formajiá IC, (Tinglyū,) Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.), Kwaengdō | Tsuyenji | 21 | (4+4) | |

| 73xxx | Finkyáse | Zúkshi (F. h.), Womenlū-S., Nároggul-T. B.,Leshfyomi-sul, PSM, Formajiá IC, Tinglyū, Yoyomi, Zúkshi (c. h.), Kwaengdō | Tsuyenji | 6 | (4+4) | spring and autumn holiday |

| 80xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Buskyueng L., Góhomi | -Pyeokchin- | 8; 16 | (5S+5); (3) | winter holidays |

| 81xxx | Pyingshum KDC | Buskyueng L., Mamshusul | Góhomi | 6; 12 | (5S+5); (2N) | winter holidays |

| 86xxx | Pyingshum KDC | - | Busakyueng ZC | 18 | (4+4) | |

| 91xxx | Pyingshum LDC | Oreppyo, Kōnil | Manlung | 18 | (3) | |

| ()=some trains, italic = extra seasonal services/trains/carriages | ||||||

| Train No. | Terminus | via | Terminus | t/d, dir. | Rolling stock | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170xx | Oreppyo | Nároggul ZC, Púlmaerong, Duma - Wenzū ZC | Yoyomi | 9 | (2N+2N) | |

| 180xx | Oreppyo | Nároggul ZC, Kippa, Kwen Wenzū Aku | Yoyomi | 15 | (2N+2N) | |

| 260xx | Unzai | Línai, Īme, Tinglyū, Duma - Wenzū ZC, Toefyei, Pītom, Kimelíngsan-shu | Jaka | 12 | (2N) | |

| 330xx | Pyingshum LDC | Toribiri, -UL31a-, -Samane- | -Luthesia- | 17 | Samane rolling stock | |

| 340xx | Pyingshum LDC | Pyingshum Z.-F., Toribiri, -UL31a-, -Samane- | -Luthesia- | 1 | Samane rolling stock | Night train |

| 360xx | Pyingshum LDC | Pyingshum Z.-F. | Toribiri | 2; 5 | (2N); (2N+2N) | winter holidays |

| 370xx | Duēkain | Kippa, Púlmaerong, Kimaéchul, Sújoshí, Pyingshum Z.-F. | Toribiri | 2; 5 | (2N+2N); (3) | winter holidays |

| 550xx | Geryong | Manlung, Jippun, Rosshi. (H. h.) | Finkyáse | 18 | (2N) | |

| 560xx | Pyingshum KDC | Pyingshum D. H., Tarappel-Finglyúson | Línai | 6 | (2N) | |

| 750xx | Busakyueng ZC | Tarappel-Finglyúson, Formajiá ZC, Formajiá IC, PSM, Kimaéchul, Púlmaerong, Kippa | Duēkain | 18 | (2N) | |

| 770xx | Pyingshum LDC | Pyingshum Z.-F., Chin-Jōrin | Shangmē | 14 | (2N) | |

| 780xx | Duēkain | Kippa, Púlmaerong, Kimaéchul, Sújoshí, Pyingshum Z.-F., Chin-Jōrin | Shangmē | 4 | (2N) | |

| 870xx | Pyingshum KDC | Pyingshum K.-K., Makalasueng, Tsumani, Busakyueng L. | Unzai | 10 | (2N) | |

| 900xx | Pyingshum LDC | (Pyingshum L. H.,) Oreppyo, (Palda,) Geryong | -UL30a- | 13 | (3) | |

| 910xx | Pyingshum LDC | Pyingshum L. H., Oreppyo, Palda | Geryong | 11 | (3) | |

| ()=some trains, italic = extra seasonal services/trains/carriages | ||||||

IC & CC Rolling Stock

KHS employs THC trains (Ataraxian: Train à Haute Célérité, Kojolese: Tōsoryokku Huwochē, lit. "high-speed liner") for its long-distance services. They are produced by the Ataraxian-Kojolese manufacturer CAR. The first train model, the THC 1, was built between 1977 and 1987, but no models remain in use today.

|

|

IC & CC Network History

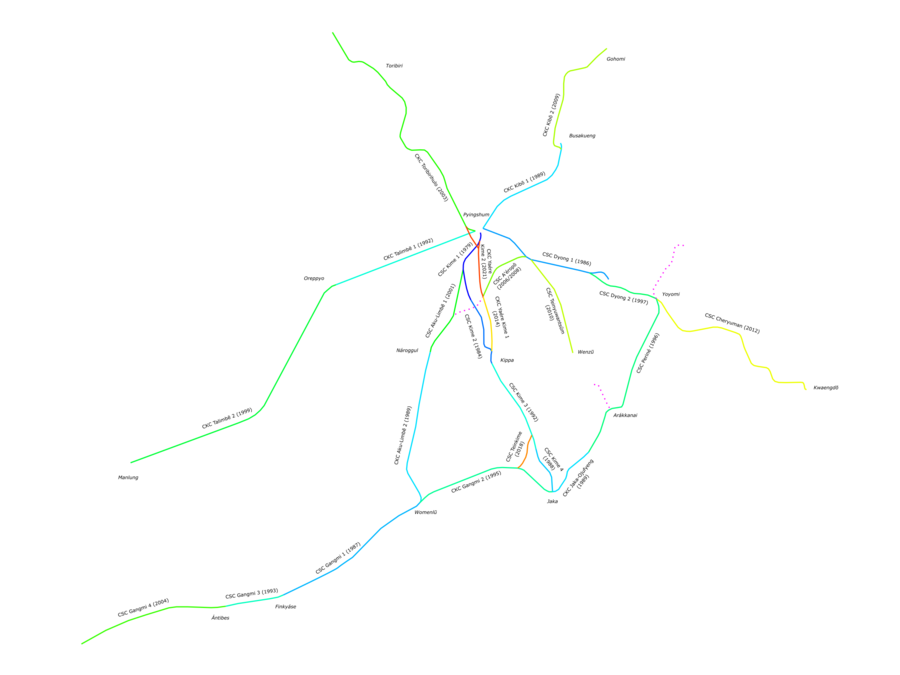

In the early 1960's, inter-city travel demand grew at a rapid pace. Due to already congested main lines, the railway sector was incapable of competing with cars and airplanes. Environmental but especially economic and geopolitical concerns regarding he dependence on oil imports spurred a political movement to seek a massive upgrade of the railway network. Inspired by similar developments in Izaland, development of high-speed passenger trains and planning for a trunk network began. The first THC train entered service in 1977 (see section above) and the first dedicated high-speed line was opened two years later. Corridors constructed on completely new alignments are referred to "Chinshimchē" (CSC, "new rapid line"), while new tracks that for most part run parallel to existing tracks (i.e., upgrade existing corridors in terms of capacity and/or speed) are referred to as "Chinkōchē" (CKC, "new high(capacity/status) line"). Both CSC and CKC are compatible with the general railway network and especially peripheral branches are frequently used by freight trains or special KCP services. The map to the right provides an overview of the high-speed network and the dates of opening.

The most recent addition is the CKC "Yaére Kime" between Púlmaerong and Pyingshum ADC on the eastern Kime bank. While this line is mostly used by CC and freight trains during regular service, its main motivation was to increase redundancy. In particular, the oldest CKC "Kime", opened in 1979, will have to close down in the 2020s for about 9 months to undergo major maintanance work.

Two extensions are to be opened during the 2020s: In 2026, the CSC A'eropō will be extended from its current end at the CKC "Yaére Kime" and connect directly to the CSC Aku-Limbē, allowing trains from UL30a and Finkyáse to safe around 20 min on their way to Pyingshum International Airport and onward to the east by bypassing Leshfyomi-sul. In 2027, a new alignment between Yoyomi and Rō will be opened, to separate local from long-distance traffic and allow for higher speeds through the Bakkyal valley. North of Rō, in 2029 a base tunnel will prolong this line further north towards lake Bōli. From then on, trains between Pyeokchin and Pyingshum will no longer have to follow the windy alignment along the Jush and Dagwan river past Īme, but will cut straight through the mountains to Yoyomi and connect to existing high-speed lines there. Besides these extensions under construction, there is also planning underway for a new alignment between Arákkanai and Belfe, closing the gap between Arákkanai and Wenzū. If planning and funding proceeds as planned, this extension is likely to open in the late 2030s.

Motortrains

KHS offers a handful of long-distance motortrain services. Travelers can load their car on a special carriage, board a sleeper carriage on the same train, and sleep while they and their car are transported over night. These services are used in particular by holiday travelers and other groups who want to use their car at their destination.

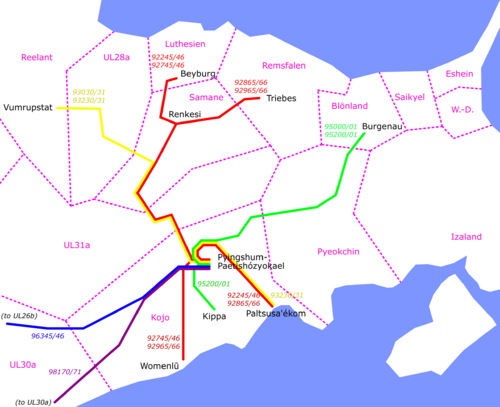

| Train no. (return) | Course | Departure (return) | Season | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92245 (-46) | Beyburg | Renkesi (coupling only) | Overnight | P. Paetishózyokael (1st unboarding) | Paltsusa'ékom | Wed (Mon) | Apr-Jun Sep-Nov |

| 92865 (-66) | Triebes | Renkesi (coupling and 2nd boarding) | |||||

| 92745 (-46) | Beyburg | Renkesi (coupling only) | Overnight | P. Paetishózyokael (1st unboarding) | Womenlū | Sun (Sat) | Apr-Nov |

| 92965 (-66) | Triebes | Renkesi (coupling and 2nd boarding) | |||||

| 93030 (-31) | Vumrupstat | Overnight | P. Paetishózyokael | Wed (Mon) | all year | ||

| 93230 (-31) | Vumrupstat | Overnight | P. Paetishózyokael (1st unboarding) | Paltsusa'ékom | Sun (Sat) | Mar-Jun Sep-Nov | |

| 95000 (-01) | Burgenau | Overnight | P. Paetishózyokael (uncoupling, unboarding) | Sun (Fri) | all year | ||

| 95200 (-01) | P. Paetishózyokael (only uncoupling) | Kippa | |||||

| 96345 (-46) | P. Paetishózyokael | Overnight | UL26b | Sun (Mon) | all year | ||

| 98170 (-71) | P. Paetishózyokael | Overnight | UL30a | Fri (Sat) | all year | ||

Airfare

Domestic air traffic plays only a minor role in Kojo's transportation system due to the country's size and an attractive road and rail infrastructure. The majority of domestic flights serve as feeder flights for onward international travel. The majority of international air traffic goes through one of the four national airports in Pyingshum, Finkyáse, Jaka and Yoyomi. These airports receive funding from the national government for capital investments, expressing their strategic importance to the nation's international connectivity. The Kime-Yuwan region is the only agglomeration designated as an "international node" in spatial planning whose airport is not classified as a national airport. Its airport, like the other regional airports, are exclusively financed by the ikis and municipalities to boost local competitiveness. In total, Kojolese national and regional airports served 104 million passengers (departing and landing, domestic passengers counted twice) and handled 869,000 aircraft movements in 2019. Besides the four national and eight regional airports there are a large number of small airfields used for leisure (lózipō) or sporadic business flights.

| City(s) | Code | PAX (million passengers) | Freight (thousand tonnes) | Flight mov. | Runways | Gates | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyingshum | PSM | 67.3 | 2,200 | 489,000 | 4 | 165 (94 bridge, 71 bus) | Map | Largest passenger and freight volume |

| Finkyáse | FIN | 10.8 | 340 | 92,000 | 2 | 48 (37 bridge, 11 bus) | Map | |

| Jaka | JAK | 7.1 | 670 | 87,000 | 2 | 32 (TBM) | Map | |

| Yoyomi | YYM | 6.7 | 310 | 71,000 | 3 | 33 (23 bridge, 10 bus) | Map | |

| Púlmaerong, Kippa, Duēkain | KIM | 3.0 | 200 | 38,000 | 1 | 18 (8 bridge, 10 bus) | Map | Focus on LCC and holiday flights |

| Busakyueng | 1.5 | 2 | 18,000 | 1 | ||||

| Kwaengdō | 1.4 | 4 | 17,000 | 1 | ||||

| Womenlū | 1.1 | 0 | 14,000 | 1 | ||||

| Manlung | 0.9 | 4 | 12,000 | 1 | ||||

| Wenzū | 0.6 | 22 | 8,000 | 1 | ||||

| Oreppyo | 0.4 | 0 | 6,000 | 1 | ||||

| Pyingshum (Longte Puechaésa) | 0.07 | 2 | 33,000 | 1 | - | Map | Mostly charter flights |

KojAir is the largest airline operating in Kojo, and the only native airline of the country. As of 2021, it is the only operator of scheduled domestic flights in Kojo. Pyingshum International Airport is the airline's hub, most long-haul flights depart here. KojAir is a founding member of the OneSky airline alliance.

Shipping

With an extensive coastline of almost 1,000 km and numerous natural and artificial inland waterways, shipping is an integral part of Kojo's transportation network. The nation's largest port in Jaka connects the country's manufacturing industry to the global economy. The largest river, Kime, allows for easy distribution of heavy goods to, from and among the industrial regions. Since the late 19th century, a number of artificial canals connects the Kime river system to Kojo's second largest river system in the east, allowing for continous inland shipping without transfer to seagoing vessels.

Passenger ferries serve as an inexpensive mean to cross the Sound of Pa to neighbouring countries especially for travellers with cars. Besides that, there are a number of both leisure and conventional ferry services on large rivers and lakes. For cruise ships, refer to Kojo#Tourism.

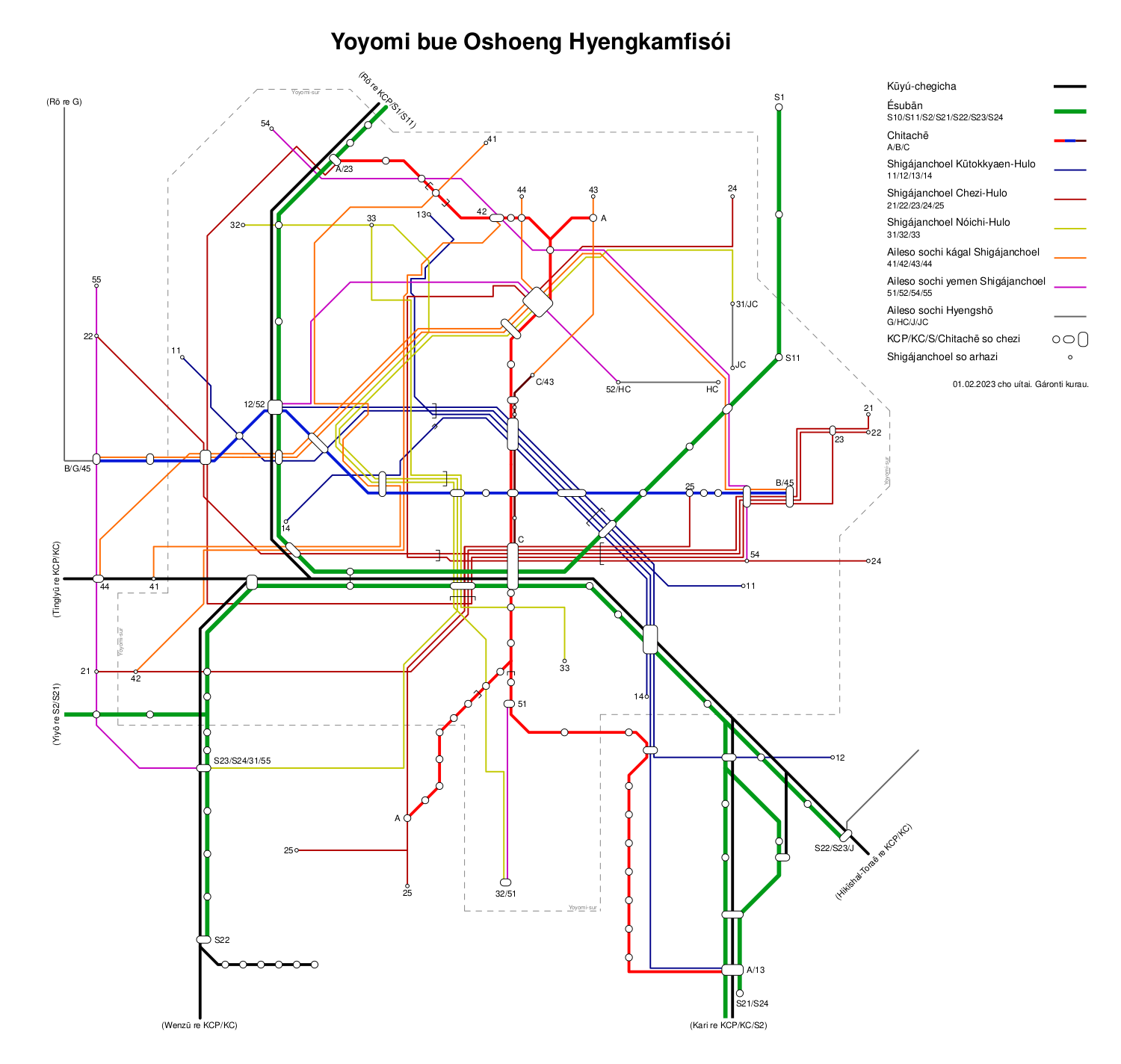

Public Transit

Pyingshum

main article: Pyingshum#Public_Transit

Finkyáse

Kippa

Jaka

Yoyomi

Economy

| ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy of Kojo | ||||||||||||||||

| Social market economy | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Zubi (Z) | |||||||||||||||

| Monetary authority | Kojo Zóngshin-weibyaeng | |||||||||||||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2021 estimate | |||||||||||||||

| • Total | $2.3 trillion | |||||||||||||||

| • Per capita | $57,850 | |||||||||||||||

| HDI (2020) | very high | |||||||||||||||

| Principal exports | Services, manufactures goods, niche agricultural products | |||||||||||||||